Be strong. Act perfect. Stay silent.

These are all stereotypes that Asian Americans are commonly held to.

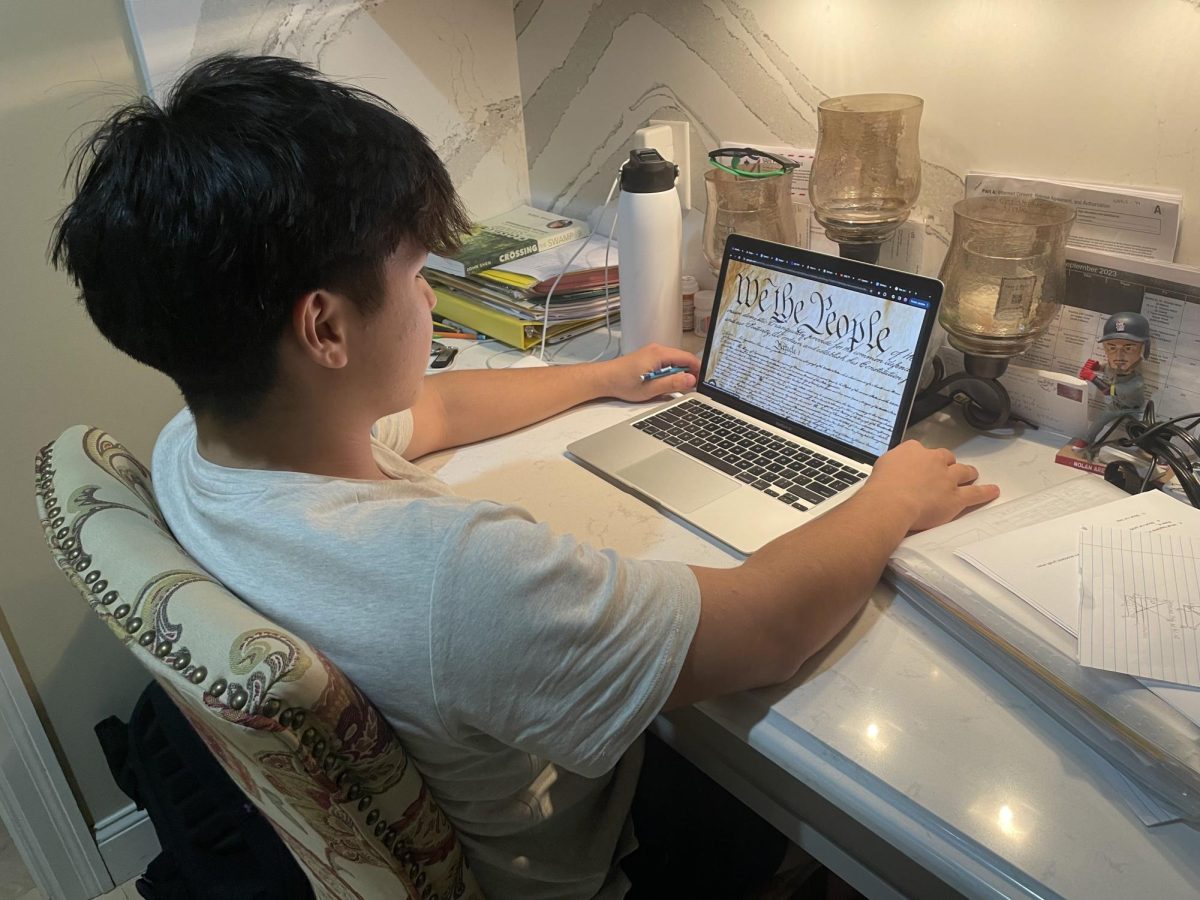

While everyone has a unique experience with mental health, studies have shown that Asian Americans are the racial group least likely to seek mental health care. With suicide being a leading cause of death for young Asian Americans, the Asian American community must work to dismantle the roadblocks stopping youth from getting the help they need.

One of these barriers is the stigma surrounding mental disorders that exists in many Asian American communities. Although every family and community is different, the Asian American community too often shies away from getting therapy or addressing mental health issues. However, ignoring the issue accomplishes nothing.

“In my personal experiences of being a child of Indian immigrants, I’ve noticed a cultural disconnect in discussing mental health,” alumna and emeritus Mental Health Awareness Club President Rachel Bhagat said. “Talking about mental health or even about receiving care used to be a very taboo topic, and is still seen as a very ‘American thing.’”

But if no one talks about mental health issues, then it only furthers the stigma surrounding mental illness and encourages others to stay silent as well.

“I’m South Asian and in our community, we don’t talk about so many things, especially being Muslim. It’s a lot more conservative,” senior Kashifa Farooq said. “People aren’t talking about [mental health]. When you don’t talk about it or you feel embarrassed, [people think], ‘Oh, no one else is doing it so I can’t do it.’ That stops them from getting help for themselves.”

If we do not speak up, mental health issues will still persist. We must first recognize that it is good for someone suffering from mental illness to get help. Seeking professional mental health care statistically has concrete benefits. With a combination of different types of treatment, like medication and therapy, between 70% and 80% of patients experience fewer symptoms of mental illness and a better quality of life.

Opening up about mental health can often be a struggle for many first-generation immigrants who still see mental illness as a threat to their families’ reputations. All too often, society inaccurately perceives mental illness, especially in adolescents, as a sign of weakness and poor parenting skills. Furthermore, stereotypes like the model minority myth only reinforce the pressure placed on Asian Americans to be “successful.” But if more Asian Americans start openly sharing their stories and their backgrounds, we can help alleviate some of this stigma and make it more socially acceptable to seek help. While it is never easy to unravel generations of stereotypes and erroneous expectations, talking about the issue more frequently and openly is a good place to start.

“When I started going to therapy, my mom was like, ‘Don’t tell anyone. People look down upon you [and] think it’s bad if you go to therapy.’ But therapy is really a thing to better yourself,” Farooq said. “I can talk about my feelings more openly. [Therapy] teaches you different coping skills and how to deal with anxiety.”

Even as we overcome the stigma towards seeking help, conversations surrounding mental health must acknowledge that therapy is often inaccessible. In America, therapists can be incredibly hard to find and finance. According to the Center for American Progress, one in three Asian Americans diagnosed with depression could not afford care due to high costs.

Furthermore, for minority populations, especially, finding an effective therapist can be even more difficult due to cultural and language barriers. People from different backgrounds may express or cope with mental illnesses in different ways. It can be hard to open up to a therapist who does not have a similar background to one’s self, especially if they have not received cultural competency training. Bhagat, who worked with immigrants and refugees through the International Institute of St. Louis, has noticed this disconnect of understanding between mental health professionals and potential patients.

“In my experiences of working with immigrant and refugee populations in St. Louis, I’ve also noticed that there is little awareness about what mental health is and how to address it. Even when there is awareness, cultural barriers and understanding between mental health specialists — therapists, psychiatrists, physicians [and others] — and patients often creates another barrier/stigma for accessing care,” Bhagat said.

For me personally, therapists — who I have been privileged to see in the first place — often make assumptions about my “strict” family or “perfectionist” personality, stereotypes commonly associated with Chinese Americans. Asian Americans are not a monolith. For example, Southeast Asians are most at risk for depression compared to other groups, while Filipino Americans have the greatest depression rates compared to other ethnic groups. As a society, we need to understand that these differences exist and avoid painting an entire group with a broad brush. Recognizing these differences would allow mental health professionals to create more personalized relationships with Asian American patients and help these patients feel better understood.

When more Asian Americans discuss mental health, it can become easier for others in our community to speak out and seek care. In addition, we must listen to a wider diversity of voices in this conversation. The Asian American label covers a huge range of ethnic groups with completely unique identities. The media often centers their coverage of Asian Americans around certain subgroups, like East Asians, so as the Asian American community discusses mental health, we must accept and promote people with mental health experiences unlike our own. By recognizing these unique experiences, we can help Asian Americans not be seen as a one-dimensional stereotype, but rather individuals with very personal struggles.

But dismantling this stigma should not be a responsibility entirely placed on the Asian American community. Stereotypes propagated by media that have long persisted in society that characterize Asians as a monolithic, perfect group only add to the pressure that many Asian Americans face to stay silent about their mental illness. Ignorance and assumptions on the part of mental health professionals are extremely disheartening for those who do seek out care. Furthermore, financial barriers often make therapy impossible for potential patients in the first place.

This is why we must support policies and programs that help make therapy more accessible. At a district level, this means continuing to provide services like mental health screenings. The district could further its reach to students who may hesitate to opt-in due to social stigmas by making the process standard — not requiring prior signups.

If we as a society can acknowledge the prevalence and impact of mental illness on the Asian American community, we can begin to work to dismantle the cultural and financial barriers that prevent many Asian Americans from seeking proper mental health care.

![Latin students pose for a group photo in front of historical ruins in Italy. From March 13 to March 23, the Latin department traversed cities in Italy to immerse students in an educational experience of a lifetime. “I enjoyed being able to learn about the different cultures. [The trip] encouraged me to see other peoples lifestyle and learn more about different histories,” senior Suraiya Saroar said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/PXL_20240318_092633493.jpg)

![From Jan. 22 through Feb. 1, Parkway West High is displaying a wide array of art pieces made by students ranging from elementary to high school. All classes were represented on the displays in both the art wing and the main foyer of the school. “[Art] benefits me because in the middle of a busy day. I can just relax and have some fun doing art and it makes me happy. I think its important that you show art in the art show so that people can get inspired by it and be inspired to create their own pieces; it’s really impactful,” sophomore Dhiya Prasanna said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/image1-1200x800.jpg)

![Moviegoers smile for a picture after watching the Bollywood movie “3 Idiots.” The event ran from 4-8 p.m. on Saturday, March 9 and was open to students across the Parkway School District. “I decided to come to the movie night because I wanted to introduce my non-Indian friends to the rich culture and entertainment of Bollywood. One of my favorite parts [of the night] was the combination of [the] amazing food and the pure comedic entertainment. [It] was unmatched,” sophomore Aryan Allu said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_5479-e1710180016483-1200x900.jpg)

![Senior Kylie Secrest volunteers at the blood drive signup table.The table provided students aged 16 and up with information about the drive and assisted them in the signup process. “We decorated the stand in the lunchroom with heart related or red decorations from either Dollar Tree or Five Below,” Secrest said. “This year was my first year doing [the blood drive] and it was fun. I got to be able to meet new people and help out the community.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/image2-1200x800.jpg)

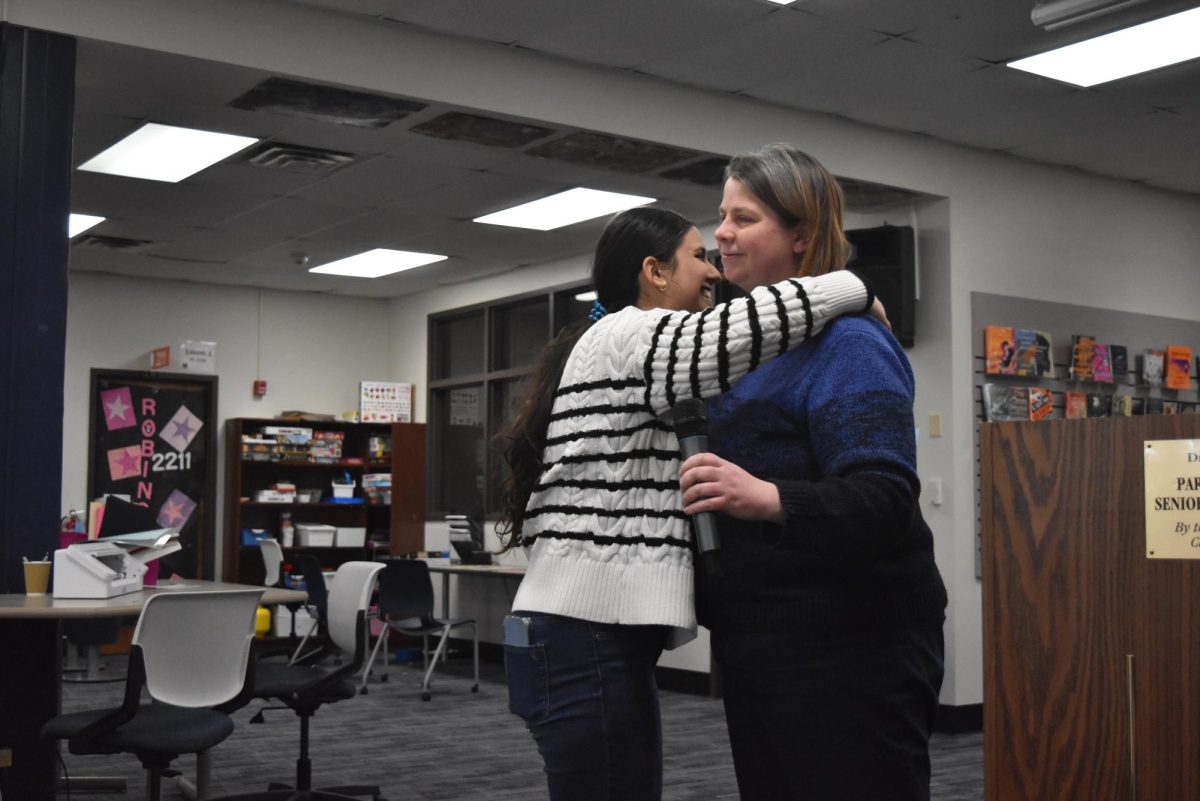

![Smiling widely, Principal John McCabe congratulates English teacher and English Department head Shannan Cremeens on winning the 2023-2024 Teacher of the Year title. Sophomore Cooper Oswald was a witness to the celebration. “We were all pretty excited. We were all clapping and standing up. We even [got to] take a picture with her,” Oswald said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/TOYvertical-1200x954.png)

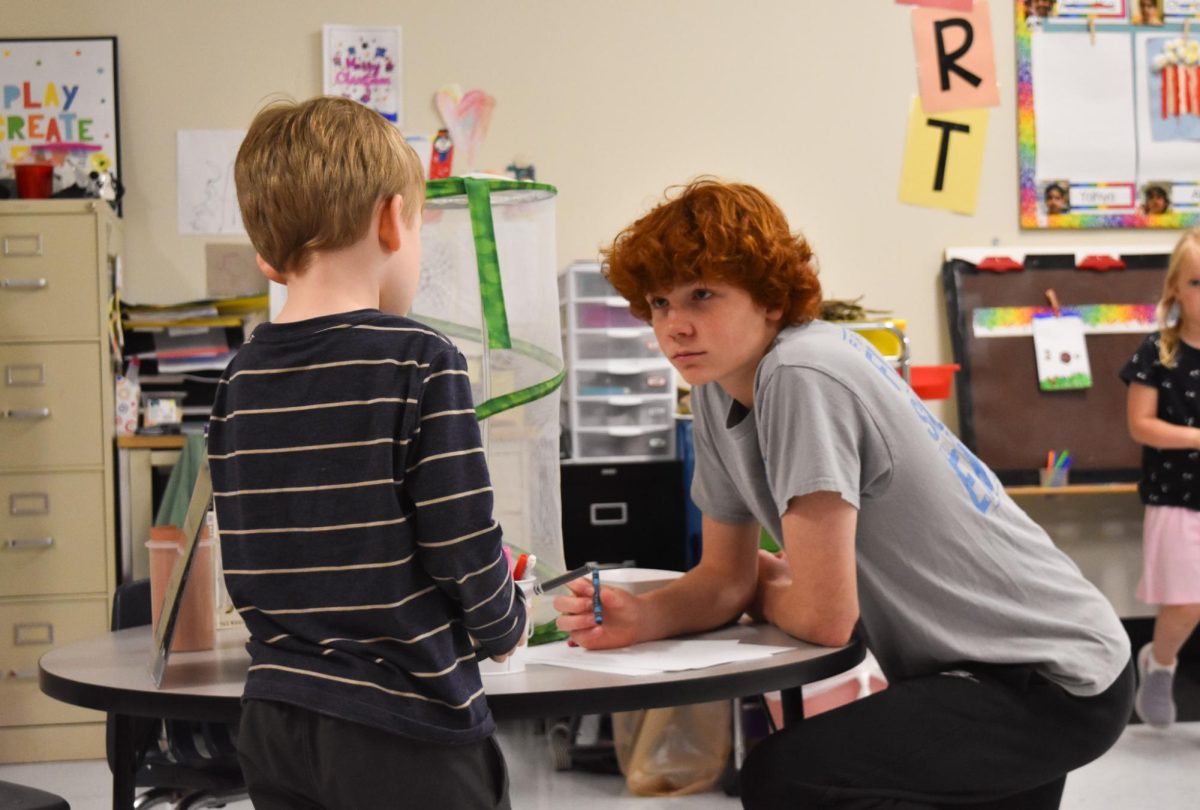

![Standing in front of the American Sign Language program’s mural, junior Brooke Hoenecke signs with freshman Darren Young. Hoenecke began cadet teaching for ASL this year alongside working towards earning her seal of biliteracy. “I was in ASL class when I received the email [that I qualified for the seal]. I was jumping up and down with my teacher and the rest of the class. One of the reasons why I took cadet teaching this year was so that I could prepare for the Seal of Biliteracy and be immersed in ASL,” Hoenecke said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/hoenecke.jpeg)

![With a keen eye for detail, senior Natalie Lashly writes her signature onto the senior hand wall. After some encouragement from her friends, Lashly applied to make the hand wall with her Lorax-inspired design. I thought the [bright] colors would be fun. Our quote on the wall is Let us grow,’ based on the Let it grow song [from the movie]. [I was hoping that the design would] make the cafeteria feel more exciting, Lashly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0099-1200x801.jpg)

![Walking onto the field, freshman Erastus Adewusi wears a pink jersey in remembrance of cancer awareness month. With the number seven on his jersey, Adewusi reflects on his life in Nigeria before moving to America. “I [used to wake up] at 5:30 a.m. and school would end at 5 p.m. [versus] now,” Adewusi said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0029-1200x800.jpg)

![Envisioning a cathedral in his mind, senior Soren Frederick puts pencil to paper and practices a rough sketch in the drawing room. Frederick grew up surrounded by a family of artists who helped him realize his passion for drawing and painting as he matured. “My family [is] very much [an inspiration] for drawing and painting. [Art] didn’t start [in the family] with me; it started with my mom and my older sister, and my older brother is very good at drawing [too],” Frederick said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0017-1200x800.jpg)

![Junior Amelia Geistler poses with her aunt, uncle and cousin. Moving through childhood, Geistler learned that having parents with a different appearance from her meant facing awkward, upsetting situations. “Something I faced [after] being adopted was that I was [treated] better when people discovered I had white parents. A childhood memory [is] when I went over to a friends house for the first time and her parents seemed to be very passive-aggressive, but when they learned I was adopted by white parents, they gave me equal treatment and ‘love’ as their white daughter,” Geistler said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Screenshot-2024-04-30-7.54.03-AM.png)

![Business and personal finance teacher Evan Stern stands in front of his classroom. After facing hardships growing up, Stern learned how to deal with them with the help of role models like his dad. “We dealt with some trauma when I was in middle school, and my dad had to be responsible for all three of us while he was working full-time. I know he had to sacrifice a lot. Im sure it was really hard for him, but looking back on it, he did a really good job . I didnt appreciate everything that he did at the time because I was so young. Now, Im engaged and probably going to have kids of my own in the next couple of years so I [am starting] to look at things differently,” Stern said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Untitled-7-1200x900.jpg)

![Holding his two smiling daughters in his arms, Principal John McCabe celebrates earning his doctorate degree. He attended Maryville University for two years and reached his goal of achieving a Doctor of Education: Educational Leadership degree after months upon months of hard work and long nights. “Im not going to lie, Im glad I have another night of my life back when Im not at school till very late,” McCabe said. “I can spend more time with my family and with my friends [who] are here at [West]. Im really happy about that.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/mccabefeature.png)

![Art teacher Katy Mangrich sits in her classroom, smiling for a picture. During her time in high school, Mangrich learned several lessons that she now passes on to her son. “The biggest life lesson that I learned is honesty. I wouldnt say I was the best teenager, but I learned very quickly in high school to always be forthcoming and honest with my parents because it always ended up serving me better in the long run. [My parents] might have been upset with me [and the mistake I made], but I wasnt going down the rabbit hole of a lie because that was just going to get me into more trouble,” Mangrich said. “I passed [that lesson] along to my nephew. Honesty is always your best approach; just don’t lie. I say that to my son all the time. Theres no advantage to lying, [and] thats a huge takeaway [from] how my parents raised me.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Screenshot-2024-01-26-10.10.12-AM.png)

![Social studies teacher Aaron Bashirian smiles in front of his classroom. Bashirian didn’t know he wanted to be a teacher from early on, but he found the choice to be a good one. “I started [teaching] because there was an opportunity for me to experiment with it. Fortunately, [teaching] was a good choice. In 2012, I became a teacher at Parkway at the Alternative Discipline Center, which is where they send suspended kids to keep being educated if they choose. I spent six years there and then I got drafted to West, [where] Ive been for about six years,” Bashirian said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Untitled-35-1200x800.jpg)

![English teacher Angela Frye stands behind her desk in her classroom. Frye went through a lot of personal struggles to get to where she is today, and with each step in her life, she carries her gratitude for those obstacles. “Everything happens for a reason. I believe in [the concept of] good energy, good karma, [from] being a good person. Those are things I dont take lightly. [Struggles] build character. You really appreciate everything you have when you have to work for everything you have,” Frye said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Untitled-8-1200x800.jpg)

![English teacher Leslie Lindsey smiles for a photo behind her desk. Growing up, Lindsey participated in many things outdoors, learning life skills that she still uses today. “I loved fishing and was never grossed out by it. I could get my hands dirty and spend time outside; even when it was cold, I didnt care. Fishing takes a lot of patience, and that is [now] a virtue of mine because I have great patience that translates into my classroom,” Lindsey said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_6632-1-e1712758336310-1200x983.jpeg)

![Since the Supreme Court’s repeal of the federal law protecting a women’s fundamental right to abortion, many states have begun to restrict access to or even ban abortion. On June 24th, 2022, Missouri was one of many states to move to ban abortion. “Missouri is giving fetuses more rights than humans who’ve been on this world for many years. If someone [wants] to have an abortion because of whatever [reason], it should be their choice. You dont know why theyre in that position and you dont know why they need an abortion,” senior Mars Allendorph said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Bang-1.png)

![Company marketing for gifts and cards during Mother’s Day and Father’s Day depicts the differences associated with the holidays. In order to capitalize on profit, large companies often include stereotype-reinforcing marketing behind parental celebration products: Mother’s Day sales typically prioritize jewelry and clothing, complete with heartfelt messages about childcare, while Father’s Day gifts tend to illustrate the father in a less serious, paternal light. “In terms of emails around those holidays, I typically get more Mothers Day [marketing] from florists or from whatever places Ive shopped at online. I tend to see more in terms of advertising and marketing,” English teacher Casey Holland said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Untitled-design-11.png)

![Frequent school shootings across the United States and subsequent lack of action have led to a chronic state of fear for many students. Recent mass shootings in schools created a new risk for students. “I’m constantly anxious about school shootings. The idea that it could happen and the prevalence of [school shootings in America] is scary. Whenever alarms go off in the school, I fear that [a shooting] might happen,” senior Carlee Priem said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Add-a-heading-27.png)

![Like many students, sophomore Medina Nanic experiences pressure to do well in school. Through continuous success and achievements, West has developed a high academic standard for students. “Because we’re seen as one [of] the better schools, we have higher standards than the [schools] who aren’t ranked as high. There’s a lot of pressure on students to do [well] and live up to those standards,” Nanic said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0029-2-1200x800.jpg)

![In the 1950s, the first recorded spikes in global temperatures were recorded, and ever since, Earth has been in the midst of a disastrous climate crisis, as rising temperatures wreak havoc on susceptible regions and destroy animal habitats worldwide. Junior Nidhi Pejathaya helped found West’s Sustainability Council to create a space where students can educate themselves about climate change and do their part to preserve the environment. “When youre going out of your way to recycle [or] reuse your clothes to save water, youre saving people. Youre saving adults, youre saving families, youre saving children. Youre saving a whole generation. Just because we dont see it doesnt mean its not happening,” Pejathaya said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/new-editorial-feature-1200x800.jpg)

![Rested against a rainbow of colored pencils, a phone plays singer-songwriter Gracie Abrams’ single “Risk.” Abrams released the song as the lead single to her upcoming album “The Secret of Us.” “We had real, true fun writing this album. There were also the occasional tears. Audrey [Hobert] and I wrote ‘Risk’ on our couch at home,” Abrams wrote on Instagram.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0009-2-1200x800.jpg)

![2023 was defined by female vocalists such as Miley Cyrus, Taylor Swift and Paramore’s Hayley Williams as their diversity and talent amongst their respective genres topped the musical charts. Williams took to Instagram to show her gratitude for having owned the No. 1 spot on Billboard’s Top 100 chart. “We know enough by now to know success doesn’t equal value. That being said, to experience the [No. 1] on this album, as this version of Paramore, is such a sweet and surreal moment to celebrate together,” Williams wrote.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2023-A-Musical-Recap-2.0-1.png)

![In perfect shooting form and with eyes on the rim, junior Tyler Kuehl is about to shoot his next basket in the last game of the season against Marquette High School. Kuehl has been playing basketball since he was 5. “Even though I played basketball all my life, the game-winning shots can be pressure, its confidence. If youre going into that shot and not thinking that youre gonna make it, its obviously not going in. And if you believe, [it will]. Thats the only way you can succeed,” Kuehl said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/unnamed-32-1-1200x1200.png)

![“At the beginning of the year, I didnt really know a lot of [the] kids in my class [so] I tried to fit in [get to] know [them better]. Then, I started having a [friend] group I [now] stay with. [Now,] if I need to ask a question to understand the material better, Ill just ask. [Having more friends and being able to connect with people] makes me feel great. It makes me feel like Im not alone in [my] classes, and if anybody needs help, [we] always have [each other] to turn to. [I’m most proud of] meeting all the people throughout the years, growing and overcoming my injury. I feel like Im usually more kind to others and prefer their opinion over mine. I [am] always [open] trying what the group wants. When Im by myself, I [can] do something for [only] so long, but when Im with other people, I [can] do anything for as long as whoever Im with wants to. [As] I go through life, I want to make sure that everything I do is fun, [but] sometimes I cant help it because [I] need to have hard [moments in life;] moments being sad, mad or upset. Whatever you [choose to] do, always have fun and make sure it’s what you want.” - Ikhana Hildebolt, 9](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IkhanaHildebolt_9-1200x800.jpg)

![“Ive always been into [doodling] with pencils and ink. I used to watch YouTube drawing tutorials and [tried] to copy them. I had so much fun with that, but I felt like I was never [that] good [at art]; it made me lose motivation to draw. If I dont feel motivated to draw, I dont force myself to. I want drawing to be fun for me. I feel like every time I start again Im better than when I left. People can [create] art really fast but Ill sit there for hours and not be [finished] with the smallest [detail.] I learned to have patience [and] take my time. I used to try to get [fancy] materials. I was so stuck in the mindset that I needed [more supplies] to get better. I would get it and then feel discouraged because [my art quality] would be the same. Be patient with yourself. You dont need fancy materials to [make astounding] art. You can just use a wooden pencil and draw an amazing piece. I enjoy making beautiful [pieces] that have a message [behind it.] Its rewarding to see hours of work pay off as the final piece comes together.” - Morgan Summa, 10](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0034-1200x800.jpg)

![“I have been playing football for a long time and have enjoyed it. This year especially, I had so much fun. I was very happy when I made varsity because freshmen dont usually make the team [their first year of high school.] I love being around the guys [on the team] and I am going to miss the senior [mentors] next year. I will never forget the impact the seniors and Coach Duncan had on me. It was not only a team, it was a family. I felt like I belonged.” - Ethan Bain, 9](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_7636-1200x800.jpeg)

![“This is my 10th year [teaching] at West. I started teaching because I struggled a lot in school, [but I decided to teach English because] I really like writing. I had a really hard time in high school and learning did not come easy to me in middle school. I would study for tests and still [did] not do well, or [I would] work really hard to write an essay and it just wouldnt come together. Once I got a grip on how to learn at the end of high school and in college, I really wanted to help students who were struggling to break down the learning process and make it easier because school is not easy for everyone. Math might not be your [specialty,] but maybe youre really good at theater, English or something else. So I’ve been helping students find what they are really good at, and [I have strived to] give them the confidence to continue.” - Diana Uffman, English](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSC_0266-1200x800.jpg)

![“One thing that motivates me to write is being understood. A lot of my writing is about myself, my experiences, emotions and problems [that] I’ve had to deal with. Writing about it makes it easier for people to understand. [My work] might not [directly] say what the problem is in the story, but I love creating these fears, experiences and weird realities to reflect the issue. [A word I’d use to describe my writing is] probably ‘odd’. My writing style is [definitely] ‘out there’. I write a lot about death and forgetting people. [But] there’s also been a lot about just being alive, and [in the moment]. I struggle a lot with derealization, which is when nothing feels real to me. I write a lot about that, and it helps me feel more [grounded]. [Writing allows me to connect to others so] that people can relate to the characters in a story [which] helps them feel more comfortable with their own emotions. Every writer implements a piece of themselves, one way or another. Just putting [oneself] in a story [allows for both a deeper level of introspection and creativity]. ” – Onyx Coleman, 9](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/pasted-image-0-1200x800.png)

![Cultural and socioeconomic barriers prevent many Asian Americans from seeking help for mental health issues. Alumna and emeritus Mental Health Awareness Club President Rachel Bhagat, who has worked with many Asian immigrants and refugees, notices clear benefits of mental health care in daily life. “Seeking out mental health care is extremely important for everyone. Regularly seeing someone to talk to about your mental health helps prevent or makes it easier to navigate mentally stressful [or] harmful situations,” Bhagat said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/unnamed-24.png)

![Senior Thalea Afentoullis backs her car into the senior parking lot. Though Afentoullis has two years of driving experience under her belt, she often feels concerned about her safety in the school zone. “From my experience, whenever I try to get down to the pit, [the junior parking lot], after school, I have to be very conscious. [Students] whip [their cars] out of their spots. The school could do a much better job by separating the timings at which students can leave because most [car crashes] happen after school when everyone’s rushing to get out of the line,” Afentoullis said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/68467-e1712933168328-1200x789.jpg)

![With her arms held high, junior Jenna Rickelman throws the ball across the pool during a girls water polo practice. With hours of practice after school and over the summer, Rickelman saw many improvements in her water polo skills. “When I look at [my] stats, Im so much better than I was last year,” Rickelman said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Untitled-design-2-.png)

Mikalah Owens • Dec 13, 2023 at 3:39 pm

Serena!!! I love this SO much. Truly a beautiful piece :’)

Sally Backer • Nov 14, 2023 at 12:02 pm

Excellent article. I love the idea of making mental health screenings a regular, mandatory screening at the district level. Providing resources to students and families after having a diagnosis would also promote the idea that getting care and support is expected. That way we can keep our community healthy, compassionate and aware of each other. Nice job Serena.

Lauren Holcomb • Nov 11, 2023 at 4:04 pm

this is so incredible

Will Gonsior • Nov 10, 2023 at 10:28 am

Meets Serena’s usual standard.

In other words, AWESOME!!!