Freshman Triya Gudipati poses for a photo at an Indian wedding. With Indians making up the largest foreign-born population in the United States, Gudipati finds it important to bond with others in her community. “The Indian community within St. Louis helps me form bonds with other people who have similar situations that I do,” Gudipati said.

Children of immigrant parents share their experiences

May 6, 2022

As the 2:30 p.m. bell tolls, students rush out of classrooms and parking lots, eager to return home. Each student comes from the same school but arrives home to extremely different lives, from values to customs to food.¬Ý

St. Louis has the third-fastest rising population of immigrants among the major metro cities of the United States. This population is represented at school, as many students are children of immigrant parents and have felt firsthand the benefits and consequences of the unique experience. Read on to learn the stories of four students who are children of immigrants.¬Ý

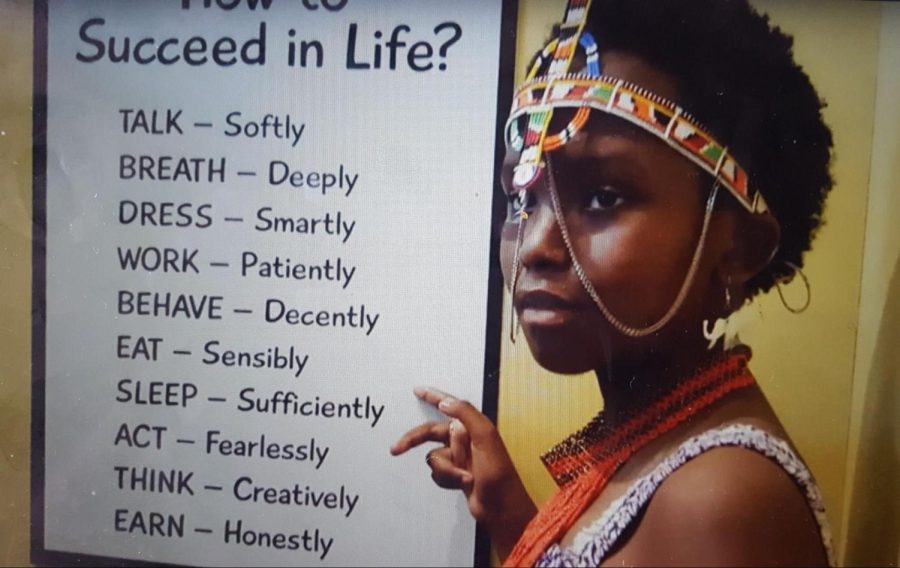

Freshman Esta Kamau

Freshman Esta Kamau attends an event representing Kenya in the Magic House with her family and other Kenyans in the St. Louis Area, wearing jewelry worn by the Masai tribe of Kenya.

In 2004, freshman Esta Kamau’s parents immigrated from Kenya in search of better education and future for their children. Initially, Kamau says that her father’s decision to immigrate was extremely difficult and Kamau’s father was unsure about their immigration, but his friends in Kenya convinced him to immigrate.

“We have a lot of family back [in Kenya]. It’s hard to move away from your parents and your relatives and leave everything behind to start in a new country that you’re not familiar with. It was difficult for them to do that,” Kamau said.

Though the distance is great, Kamau‚Äôs family travels to Kenya almost every two years. Kamau has visited Kenya four times in total, most recently in the summer of 2021.¬Ý

“It’s very relieving to see [my family in Kenya], especially if I haven’t seen them in so long and the only way I can talk to them is over text or call. It’s a very relieving and overly happy moment to finally see them after such a long time,” Kamau said.

Kamau believes that being a child of immigrant parents can sometimes make her feel like an outcast, especially due to comments on her parents’ accents. While her parents have an accent, Kamau says she is used to it and doesn’t notice it anymore.

“Being an immigrant gets hard because some people will comment on people’s accents. Whenever someone meets them for the first time, they always ask, ‘where are you from?’ I feel like it’s easier for me [because I don’t have a heavy accent], and people don’t ask me the same questions.’ I think it’s easier for me than my parents because of the stuff they’ve already gone through,” Kamau said. “When you’re put into a situation where you’re called out for having a different accent than everyone else, it’s kind of hurtful.”

Prior to moving in seventh grade, Kamau attended a different school and says she faced discrimination and bullying in elementary school. Third grade is when Kamau began to notice that she felt different from her classmates, in part due to her last name.¬Ý

“Not having the same American last name as everyone else is kind of off-putting. When I was in elementary school, kids were unaware and insensitive, but they didn’t know that they were [being] hurtful. I would feel left out of things because people would always comment on my last name and purposefully pronounce it differently even though I would correct them,” Kamau said. “I started getting treated differently and people started making fun of my last name, and whenever my parents would show up to school, people would say insensitive things. I’ve been feeling that way for a while. I did get bullied or made fun of sometimes for being an immigrant or having parents that are immigrants. I felt like I was kind of ashamed of my parents being at the school premises. Because of that, the students would make fun of me after my parents left because of my parents’ accents or the way they looked.”

After moving, Kamau has felt more accepted due to the community of immigrants both at West and locally.¬Ý

“There’s a very big mix of people that are from everywhere [at West]. I feel more accepted because I’m not the only one. I think people are more accepting and people are more respectful,” Kamau said.

Kamau has found a community here within the JV Poms team. Initially, Kamau felt ostracized as the only minority on the team, but she says a conversation with her dad changed her outlook.

“I was the only Black or Kenyan girl on the [Poms] team, and my Dad was telling me to accept that I am the special one because I am the minority of the group,” Kamau said. “[Being a child of immigrant parents] has made me become a leader. [When joining clubs], sometimes I feel like I am the only one that’s alone because I’m normally the only one that’s from the place that I am from. My parents have always taught me to be confident about where I am from and know that I am the minority, so that means I’m the special one.”

In regards to academics, Kamau feels that she faces obstacles as well. Kamau cites stress resulting from being the child of immigrants as an additional pressure that comes with school work.

“In minority countries, there aren’t as good education systems as there are in America. So, immigrant parents tend to tell their kids to study harder, make sure that they get good grades and make sure that they don’t have any missing assignments. [They] want their child to have a better future than they did. In a way, that’s good, but also I do feel really pressured by my parents because they constantly remind me about school. Sometimes I feel like that’s the only thing that they talk about with me,” Kamau said. “I wish teachers would know that it is very stressful at times because immigrant parents are always suggesting that you study or they always bring up academics or making sure that you’re on top of your grades. I wish that teachers would be more sensitive and more [understanding] of what’s going on with other students and their situations. It really matters to know what they’re going through.”

Though Kamau has never lived in Kenya, she still experiences the Kenyan culture by having gatherings with other Kenyans in her community or city, cooking Kenyan meals and wearing and learning about Kenyan clothing styles.¬Ý

“My parents have been living here for so long that they have already inherited the American way of life. They’re already adjusted and they already have the American culture also. I still have a sense of the [Kenyan] culture even though I’m not constantly in the country itself,” Kamau said. “Having a mix [of cultures] has really benefited me and changed my style.”

As a child of immigrant parents, Kamau says that she has encountered many stereotypes and misconceptions relating to her situation and her culture, specifically about the continent of Africa.

‚ÄúKenya is an African country, so a lot of people in the past have tended to have really harsh stereotypes. For example, people think that the entire continent of Africa is basically poor and doesn‚Äôt have any clean water. That‚Äôs not necessarily true. There are countries that have less than others, but specifically, the country where I‚Äôm coming from is a really good country. There is clean water, and there are resources that everyone in America also has there,‚Äù Kamau said. ‚ÄúI don‚Äôt think that the stereotypes really fit anymore because [African countries] have progressed over time. That stereotype is very insensitive and people don’t really know what they’re talking about because they haven’t actually experienced or gone to that country or continent itself.‚Äù

Kamau believes that people should be held responsible for educating themselves to not further stereotypes.

“A lot of people aren’t aware of the actual conditions of any country that they may have negative stereotypes about. Not every country is how you think it is, so you need to pay more attention and educate yourself,” Kamau said. “I feel like a lot of people need to be more educated on other people’s situations and know that [immigrant children are] not any different from you. They’re also human. They’re also people. I feel like people should be more aware of what they’re saying or who they are around.”

While Kamau believes that being a child of immigrant parents comes with a variety of positive and negative effects, overall, she is grateful to have the opportunities that accompany the fact that her parents immigrated to the U.S.

“I’m very grateful to have an opportunity to move to America. My cousins, not all of them have that opportunity back in Kenya. I was granted that opportunity because of that green card and now I have a better education and better future. Since [we] immigrated, I feel like I have a better chance at succeeding in life,” Kamau said. “Being a child of an immigrant is really cool because you know where you come from, and you know your traditions and your culture. Learning about other people that are immigrants too is really fascinating. Being an immigrant has some side effects like negative thoughts going through your head and also some positive things that you go through. It’s really cool to have a culture within different countries. You have a sense of different cultures and you get to experience both.”

Freshman Samir Shaik

Freshman Samir Shaik takes a photo with his friends dressed in traditional clothes during a Hindu holiday called Dusshera.

While freshman Samir Shaik’s parents immigrated from India 20 years ago in search of career opportunities, Shaik still tries to maintain contact with his family in India through technology, despite the challenge that distance poses.

‚Äú[My parents‚Äô] families are in India. Even now most of their families are in India. It’s sad to think about, but I don’t really have that strong of a relationship with a lot of my aunts, uncles and cousins who are still in India. I don’t see them on a day-to-day basis like people who have family here would. I don’t really think about them that much, but whenever I get to video call or chat with them, it’s always great. I don’t have that strong bond [with my family] that kids who have family that live in [the U.S.] would have,‚Äù Shaik said.¬Ý

Shaik says that attending school in the U.S. has revealed cultural differences to him between his own culture and that of his peers, such as different food, cultures and relationships with parents.

‚ÄúIn elementary school, I didn’t really notice any [differences from my peers]. We were all having fun. It was just one big community,‚Äù Shaik said. ‚ÄúBut as I got older, I noticed disparities. I started noticing those things, but every parent is different. Every student is different. It’s just about accepting our differences.‚Äù

Shaik has traveled to India three or four times and has noticed cultural disparities in his travels as well. Regardless of any differences, Shaik feels that an individual’s culture makes up a large portion of their identity.¬Ý

‚Äú[The cultural disparities] take a little bit of getting used to, but it’s always fun to see my family in person and not through a video call screen. Culture and daily life are just really different. Everyone dresses differently compared to the U.S. and the social customs are different. It‚Äôs a culture shock to me,‚Äù Shaik said. ‚ÄúCultural identity is a big part of who we are [and] who everyone is as a person. Different cultures will produce different people. You‚Äôre a product of your culture. I’m glad I get to experience this culture because it allows me to [have] a unique experience that not many American kids will get.‚Äù

Around 15,000 St. Louis citizens were originally born in India. Shaik feels that the Indian community in St. Louis is very strong, and by connecting with them, he finds a sense of comfort.¬Ý

‚ÄúI have a lot of friends who are Indians, and I always like to meet and talk to Indians at school and out of school because we have commonalities between us with [our] culture, so we always can relate a little bit more. It builds a bigger, stronger community that can allow more people to feel welcome and feel accepted,‚Äù Shaik said. ‚ÄúI feel like immigrants have stronger relationships with other immigrants. The Indian community in St. Louis is really tightly knit. Our family has a pretty big community of friends. Whenever I go to gatherings, I feel this extra warmth, and I feel this extra sense of community that I don’t really feel when I go to American parties.‚Äù

Shaik has also encountered stereotypes as a result of his culture, such as the misconception that immigrant parents are extremely harsh on their children in regard to academics and career choices. However, Shaik feels that he does not fit the stereotype as both of his parents have careers in the STEM field, but he doesn‚Äôt feel pressure to enter the same field.¬Ý

‚ÄúA stereotype is that all immigrant kids are in all honors classes. Their only life is in school. This isn’t true, at all,‚Äù Shaik said. ‚ÄúPeople perceive immigrant countries that have a lot of immigrants in the U.S. as just churning out all these super-smart genius people, and then they see all these kids at school who are like that, and they expect them to be the same. It’s sad because they’re stereotypes. They’re not true. It’s really hurtful when people always spread them because [they‚Äôre] spreading lies, basically.‚Äù

As a child of immigrants, Shaik has noted a variety of positive and negative consequences, specifically within his culminating cultures.

‚Äú[Being a child of immigrants] has its ups and downs. There have been some times where I wish I wasn’t a child of immigrants, but there have also been times where I really loved that I’m a child of immigrants,‚Äù Shaik said. ‚ÄúI get to enjoy this different culture that is not as prevalent in the U.S. We get to practice [these] really cool, really different cultural traditions. You just have to accept your culture and be who you are. [You have to] embrace your culture [and] embrace our differences, because that’s what brings us together.‚Äù

Freshman Triya Gudipati

After 16 years of living in the U.S., freshman Triya Gudipati‚Äôs parents finally received their green card around a year ago. Gudipati‚Äôs parents were born in India but immigrated to the U.S. in search of better educational opportunities.¬Ý

‚ÄúAt first, it was really hard for [my parents]. They were broke, they had no money, they didn’t know anyone here and they were working,‚Äù Gudipati said. ‚ÄúBut, once they made their friends and established themselves a little bit, it definitely got easier.‚Äù

Although Gudipati was born in the U.S, she says that she can feel different from her peers. Gudipati began to go to daycare around the age of two or three and first noticed a difference.

‚ÄúI knew that my friends are different [from me]. I knew, ‚Äòhey, they’re not the same race.‚Äô They’re not Indian. I’m the one who‚Äôs different,‚Äù Gudipati said. ‚ÄúI have a different culture than most of my friends. Most of my friends or families are in the [U.S.]. My family’s Indian so I have a different side of life than other people here do.‚Äù

Gudipati celebrates her own culture by interacting with a more local Indian community in St. Louis, as well as visiting India every summer.

‚Äú[People within the Indian community in St. Louis] can relate to me more. They have similar experiences to what I have,‚Äù Gudipati said. ‚ÄúI was taught to always celebrate all different types of cultures. I think it’s cool that everyone’s different and everyone’s diverse. I know I’m different, but it’s not a bad thing that I’m different. It helps me learn about them, and they learn about me.‚Äù

Gudipati says that she tries to challenge the cultural misconceptions and stereotypes she encounters and educate others. One avenue through which Gudipati says she challenges cultural stereotypes is participating in wrestling.

‚ÄúThere’s definitely stereotypes about how there’s pressure for you to be academically advanced. Most of those aren’t really true. Of course, my parents want me to do well, but they’re like, ‚Äòif you’re happy and you’re doing what you want to do, we‚Äôre fine,‚Äô‚Äù Gudipati said. ‚ÄúI generally surprise people. When they talk to me, they realize that I’m what they think of when they think of India. And so I‚Äôve kind of gotten used to being like, ‚Äòyeah, it’s not really true.‚Äô I like that I’m breaking what they think of as what an Asian person would be.‚Äù

Gudipati believes it is important for her teachers and peers to make a concerted and mindful effort to be respectful of different cultures. Gudipati has noticed that people around her can make uneducated mistakes, such as interchanging the words Hindi and Hindu.

‚Äú[I wish my peers and teachers knew] to try to be mindful about the way you word things. Sometimes they can be worded offensively or just they’d say things that make them seem uneducated. It doesn’t really bother me, but it would be nice if they could at least use the proper terminology,‚Äù Gudipati said. ‚Äú[It‚Äôs important to educate yourself because] I feel like it definitely helps [you] see what other people are going through and helps people empathize with others.‚Äù

Gudipati says that being a child of immigrant parents has taught her to work hard and has acted as motivation throughout her life.¬Ý

“[Being the child of immigrant parents] makes me want to do better because [my parents] left their country, and they came to a whole new place for me and my brother to have a good life. I want to make the best of that situation,” Gudipati said. “It makes me want to try harder and be more determined to do things and be the person that would make them proud.”

Senior Wilson Gao

Senior Wilson Gao poses for a photo as a fifth grader in front of the Temple of Heaven, in Beijing China.

Before senior Wilson Gao was born, his parents immigrated from mainland China and Hong Kong, respectively, in the 1990s in order to study.¬Ý

“Their families had to work hard to support them to get enough money so they could come over here and study. My mom even told me that she ran out of money after her first year studying here, so she had to get a scholarship,” Gao said. “We grew up experiencing different circumstances. Our parents came to the U.S. after having grown up in faraway places. I think from that, they gained different perspectives on the world and how we view other people.”

Gao still has family in both China and Hong Kong and communicates with them primarily through video calls. Gao has visited China three times, mainly touring along the East Coast and visiting relatives.¬Ý

“[One cultural difference I have noticed is that] in China, one thing that I remember is that there were a lot of gifts, even in business transactions. In America, that isn’t a commonplace thing. Another thing is haggling. Unlike in America, you can see bartering back and forth about prices,” Gao said. “Besides that, I would say [China] is a lot more hectic. It’s not as organized as in the U.S. where there are wide streets and sidewalks everywhere. There were a bunch of people walking everywhere and a lot of cars driving. It’s very noisy and big compared to St. Louis.”

Gao has lived in America for his entire life and feels that being the child of immigrants offers him a unique experience as he is able to experience both American and Chinese culture simultaneously. For example, the Gao family primarily cooks Chinese food at home.

“It’s definitely a unique experience [being exposed to both American and Chinese cultures]. I really enjoy it. Having more experience in both cultures is definitely a good thing,” Gao said. “It expands your worldview and makes me appreciate the differences and similarities between the different cultures.”

Though Gao’s parents immigrated to the United States almost 30 years ago, Gao believes that their immigration experience has ultimately impacted him in a major way.

“[My parents being immigrants has] definitely influenced who I am. They came from a different continent so they grew up around a different culture. My parents have always emphasized that I should work hard and never slack off because it’s just something that’s [not] part of the Chinese culture. Living here, I’ve learned to appreciate personal freedom. Being a part of an immigrant family has definitely influenced who I am,” Gao said.

Gao believes that his parents have instilled values of hard work and dedication in him.

‚Äú[My main takeaway from my parents being immigrants] is to always keep moving forward, even when life gets hard, like when my mom ran out of money and for one week my dad lived on nothing but eggs and bread.¬Ý Now, my parents are able to afford a nice house and enjoy life. Even if you are struggling, make sure not to submit to that struggle,‚Äù Gao said.