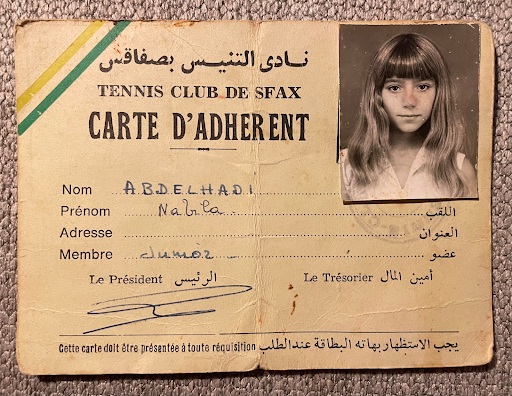

French teacher Nabila Harig’s Tunisian background is hard to miss as a French student. She often incorporates details about her experience growing up in a francophone country into lesson plans and uses personal anecdotes to give students a perspective of the french-speaking world. What students don’t know is that Harig had a very long journey to becoming a French teacher.

Born in Tunisia, Harig was a child during a time of immense change in her native country. Tunisia, after becoming independent, was starting to become more tolerant of all religions and give women more rights. These changes allowed Harig to attend a Catholic school as a child, something that wasn’t common in the predominantly Muslim country.

“Those were the best years of my life because it was such a clean environment and there was an importance of education and values; we were a mixture of different people,” Harig said.

Harig’s stability at Catholic school was upturned, however, when changes in the political and social climate in Tunisia forced her to find a new school.

“The government decided that we should not have any Catholic private schools in this country. It was a lot of stress for me because I wasn’t used to public schools and I never dealt with people other than those people in the private schools,” Harig said.

Many students who were also displaced by the Catholic school closure decided to continue their education in boarding school in France. Harig’s family made the decision that she should follow the other students and begin attending boarding school.

“In fourth grade, I moved with them. They moved their institution about two hours away from Paris,” Harig said. “It was seven beautiful years of my life— not because I moved away from my parents but because of the values [we had at school].”

After boarding school, Harig’s father convinced her to come back to Tunisia for the time being and get her “Bac,” a degree that students can get at the end of high school. Earning a career or technical “Bac,” [the highest distinctions of the baccalaureate] can mean entrance into a prestigious college. After earning the “bac scientifique” with honors, she made the decision to come to America.

“At first it was just a joke because usually, [in Tunisia] we don’t go to America. We go to France. I applied to an American University and then to another medical school in France. I spent six months waiting for the decision and I got accepted with a full scholarship to go to the States,” Harig said. “I started packing and, to be honest with you, I did not think I could do it.”

Harig says she faced a lot of self-doubts and questioning from others in her community on her decision to travel to America for an educational scholarship. Tunisia was still rapidly changing at the time, and not everyone approved of women’s rights, expanded educational opportunities and generally being an independent democratic country.

“[America is] far away from home. Language is the biggest barrier because English was a third or fourth language for me. My dad did not want me to go to the States since he just got me back from France,” Harig said. “The society was just starting to be emancipated so it was only 50-50 of the people who approved of whether a young girl could go to America by herself.”

Despite the uncertainty around this change, Harig traveled to America on an educational visa and attended the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, but when she learned that her Tunisian friend was attending Ohio State University, she decided to transfer.

“I started teaching as a teacher’s assistant (TA) and I had a bit of room to drop my Tunisian scholarship and study whatever I wanted. I started studying economics and French,” Harig said. “It was like being on my own. The scholarship was not coming and being a TA paid for my tuition. I had to keep being a student because I came on a student visa; it was my only way of staying in the States.”

Harig continued her studies and was on track to achieve a Ph. D. at Virginia Tech. However, right when she was finishing her thesis, her topic about NATO became obsolete due to political developments and she had to start over again. Instead of spending years reworking her Ph. D., Harig decided to contact a friend of hers who worked at Washington University.

“I came to St. Louis following my friend. That’s how I got a job at Kirkwood and met my husband and had a kid. I didn’t return to Tunisia for seven years. It was the hardest road to get my green card,” Harig said. “They told me you have to go home for at least two years and come back because they invested in your education and you had to go back and invest in your country. I was stuck.”

Harig returned to the United States after two years in Tunisia and eventually gained full citizenship and a green card. She settled down at Kirkwood High School, teaching French, and eventually moved to Parkway West. Harig is proud to be here to stay.

“The road was very rocky to get here, but that’s the point,” Harig said. “I’m at a place where I chose to live. I feel like I achieved something and I feel like I climbed the mountain and now I’m at the top.”

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Amid teaching a lesson to her AP Calculus BC class, Kristin Judd jokes alongside her students in their funny remarks. Judd has always enjoyed keeping the mood light in her classroom, along with on the volleyball court. “[I enjoy] that side talk where you see [or] overhear a conversation and chime in, or somebody says something funny,” Judd said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/image-1200x730.jpg)

![Eyeing the ball, junior Ella McNeal poses for her commitment pictures at Clemson University. McNeal’s commitment comes after months of contact with top Division 1 soccer programs. “ It has taken a lot to get to where I am, but I know that [what] I've already been through is just the beginning, and I can't wait for what is to come,” McNeal said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_4926-1200x900.jpeg)

![Senior Adam Zerega stands with senior Dexter Brooks by farm equipment. Zerega often worked with friends and family on his farm. “I've been able to go to my family's farm since I was born. I [spend] at least three weekends a month [on the farm], so I'm there all the time,” Zerega said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IMG_4872-1200x900.jpg)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

![Junior Fiona Dye lifts weights in Strength and Conditioning. Now that the Trump administration has instituted policies such as AI deregulation, tariffs and university funding freezes, women may have to work twice as hard to get half as far. "[Trump] wants America to be more divided; he wants to inspire hatred in people,” feminist club member and junior Clara Lazarini said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Flag.png)

![As the Trump administration cracks down on immigration, it scapegoats many immigrants for the United States’ plights, precipitating a possible genocide. Sophomore Annabella Whiteley moved from the United Kingdom when she was eight. “It’s pretty scary because I’m on a visa. When my visa expires next year, I’m not sure what’s going to happen, especially with [immigration] policies up in the air, so it is a concern for my family,” Whiteley said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0077-7copy.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

![Red, white and blue, the American flag holds the values of our democracy. The fight that we once endured has returned, as student journalists and senior correspondents across the country are losing their voices due to government control. “[Are] the White House and [the] government limiting free speech [and] freedom of the press? Yes [they are],” chief communications officer of the Parkway School District and former journalist Elisa Tomich said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Untitled-design-14.jpg)

Blair Hopkins • Jan 20, 2022 at 3:32 pm

C’est très intéressant! J’ai beaucoup appris sur le fabuleux destin de Madame Harig 🙂 C’est un article génial, Thomas.

katie • Jan 20, 2022 at 2:36 pm

c’est très bien!!