‘They already trust the guy’

September 18, 2019

Junior Laura Young refines her speech after receiving feedback from teammates. Young and her debate partner, junior Zoey Womick (not pictured), placed second in the Greater St. Louis Conference in Public Forum Debate for the 2018-19 season. “Being a girl in debate is sometimes intimidating because when you go up against really good teams that are two males or even just one guy, they oftentimes have more of a reputation than the really excellent all-girl teams do,” Young said. “A lot of events are also male-dominated, which is also extremely intimidating because they come off as very charismatic and have so much more of a reputation that it’s just really scary to go up against them.”

The pandemonium of the preceding days has filtered into the type of ambience teetering along the fringes of awkwardness and romanticism that only a speech and debate tournament could provide. A line of competitors donning poorly-sized suit jackets and ties in dire need of straightening face directly towards an uninspiring wall in an equally uninspiring hallway.

In every crevice of the hosting high school, they restlessly scrutinize notes and complete last-minute rehearsal speeches before wading into otherwise empty classrooms. The high-budget wardrobes on display for the ensuing rounds are met with a setting that is anything but. Junior Kathryn McAuliffe scans the room before assembling a makeshift podium using a stack of textbooks she cobbles together. Both she and her opponent anxiously fidget while the judge writes their names onto the ballot and finally signals for them to begin.

Each side’s opening speech is accompanied by a three minute cross-examination period. It is, for all intents and purposes, a free-for-all. Debaters may use their three minutes to ask whatever questions they please. Some contentiously raise their voices in what quickly escalates to shouting matches while others, cornered by difficult questions, aimlessly ramble in hopes of stalling out the clock. It will be McAuliffe’s only opportunity to directly clash with the opposition, but she secretly dreads the experience.

“A lot of girls are aggressive and that can really affect their ballots. I never interrupt somebody even if they’re talking too long in cross-examination,” McAuliffe said. “I’ve been talked down to in the middle of rounds, so I’m not huge on cross-ex. I knew the questions were pointless because he was going to twist what I said anyways.”

Now, McAuliffe’s male counterpart presents his opening statement. Only, he addresses neither the evidence she cites nor the arguments she makes. Instead, he simply responds by claiming that she has a “basic misunderstanding” of the topic at hand to a slight nod of approval from the judge.

Junior Grace O’Connor prepares to compete in Poetry Reading at the Oakville Novice Events Round Robin Jan. 19, 2018.

“It just really hurt. Attacking the opponent rather than the case is a shoddy way to get out of an argument when you don’t have anything to say. It devalues the practice of speech and debate. We’re here to debate ideas, not to debate one another, and I don’t want to be called stupid,” McAuliffe said. “What’s inherently in speech and debate goes into what’s in our society because traditionally men have always been seen as the more political figures, and speech and debate is a political activity–they go hand in hand. You automatically assume that he is political, so I think, as a judge, you already assume that he has a command of the facts, and you’ll trust every single piece of information that he’s saying. By that point, you’re just evaluating the opinion. With inherent biases, they already trust the guy who’s about to give a speech more than girls.”

Borgsmiller has seen plenty of rounds similar to this one in her 12 seasons of coaching. Five years ago, a student of hers who would go on to win the MSHSAA State Championship in the Original Oratory public speaking event failed to even qualify for NSDA nationals with the same speech. She learned the harsh lesson that certain messages female competitors convey may fall on unwilling ears.

“Her senior year, she wanted to do a speech topic about how it was okay for females to be single, that they didn’t need to have a counterpart, typically a man, to define them. She ended up winning state, which was kind of a shock to all of us, not because she wasn’t successful, but because she wasn’t consistently successful,” Borgsmiller said. “Those people decided they wanted to hear her, but when we had our qualifying tournament for nationals, she got through three rounds and was straight [first place rankings out of six competitors], and then in round four, she had an all-male panel: got a five. Round five, she had an all-male panel, got a five and went out. There’s this line. You can say, ‘screw it–I’m going to say what I want, and say it the way I want to,’ and sometimes that works, but it’s definitely not going to work all of the time. I think that’s a perfect example of why that’s the case.”

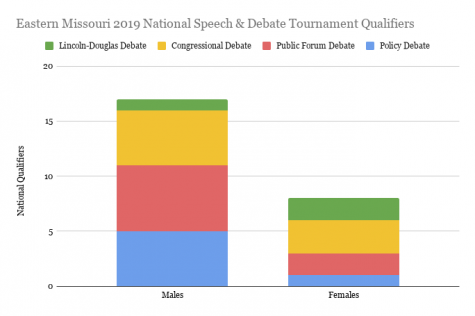

Of the Eastern Missouri district’s 25 qualifiers to the 2019 National Speech & Debate Tournament in Congressional, Policy, Public Forum and Lincoln-Douglas Debate, 17 were males to just eight females.

A chart displaying the Eastern Missouri district’s qualifiers to the 2019 National Speech & Debate Tournament.

“You have to work harder [as a female competitor], but I think that’s what makes it more satisfying when you do win or when you see that success or when you change somebody’s mind because you know you had to work three times as hard as the other guy, and you still beat him,” Borgsmiller said. “Perhaps at its core, that’s why it was so transformative for me, to feel empowered in that way and to know that I could make a difference despite the fact that I had to work a lot harder than other people had to. That replicates reality. The only way you can make change in the real world too is to change the hearts and minds of those that are on the ground.”

Yet in the face of these obstacles, the greatest act of resistance to sexism in speech and debate just might be females partaking in the activity.

“I think if we’re going to do this from a grassroots level, it has to come from more females participating and being willing to take the risks like my previous student was, which is hard to do because I think sometimes we want to win more than we want to make change, and that’s okay,” Borgsmiller said. “This is a group of teenagers. It’s super impressive that anybody wants to stand up and speak in the first place, but I just encourage more females to try this so they know that their voice can have power and make change.”