Sexism in speech and debate: competitive speakers’ fight for their voice

September 11, 2019

It is the conversation that speech and debate coach Cara Borgsmiller is forced to have several times each season.

“I talk openly about it, especially the first time they get a ballot that says something about it.”

You were rude to your opponents.

Your tone of voice was annoying.

Your skirt was too short.

“It” is the bias that women must confront at every speech and debate tournament.

Despite the National Speech and Debate Association’s (NSDA) mission statement emphasizing “a diverse community committed to empowering students,” female members of the community are voicing concerns in response to pervading sexism in both the debate space and society as a whole.

I have participated in nearly 100 speech and debate rounds, yet certain facets of the activity have been little more than afterthoughts for me as a male. No single round better encapsulated this than the fifth and final round of the Greater St. Louis Conference Tournament Oct. 20, 2018. That round would determine whether or not my male partner and I clinched the tournament championship–although we were hardly dressed for the occasion. My female opponents’ carefully-selected formalwear likely cost hundreds of dollars, the slightest imperfection posing humiliation and a risk to their ethos. As for my partner and I, we felt entirely comfortable expressing ourselves however we pleased. To pay homage to a late teammate and protest lavish clothing norms we believe discourage low-income students from participating in speech and debate, we sported t-shirts and jeans–with relatively little consternation.

Never during the round itself did I think twice about curtailing my voice modulation, interweaving lighter, conversational speech with a more authoritative tone whenever circumstances prompted one. Both sides in the debate incisively asked and responded to questions during cross-examination periods, but when it came time for the judge to declare a winner, their ballot contained a message for the two girls: “Your disrespect towards your opponents lost you the round.” While the judge reprimanded them for discourtesy and snarky presentation, my partner and I received praise for our poise and assertiveness. What implicitly boosted our credibility only undermined the supposed merit of the girls’ arguments.

Sexism in speech and debate underscores much broader issues that I myself will never experience firsthand. In order to better understand this complex but alarmingly prevalent subject, I sought the insight of my female teammates and coaches. What follows are their stories and perspectives on matters ranging from dress code to voice tone to everything in between.

‘Viewed as a mannequin’

Before the first round of the tournament, junior Grace O’Connor rehearses her Program Oral Interpretation (POI) performance at the Randy Pierce Winter Classic at Pattonville High School Dec. 7, 2018. Competitors create a performance using various published works of prose, poetry and drama around a central theme. “It hurts when people don’t listen to your piece because you spend so much time working on it, and you do really pour your heart into it,” O’Connor said. “When people dismiss it simply because of your gender, it’s so heartbreaking and for a lot of people it’s not worth it [to continue competing]. It’s not worth the emotional labor and the aspects of just not being heard because of what you look like or what your gender is.”

Alumna Kristina Humphrey struggles to articulate her reaction into words.

“Are you kidding me?”

As is the case on any Monday following a weekend tournament, members of the speech and debate team flood room 1511 to review their ballots containing feedback from judges. The typical groans over misunderstood arguments and baffling “reason for decision” statements arise, but Humphrey’s judge cited something unrelated to her performance when assigning scores and rankings.

“I wore a red dress, and the judge took off points because it was ‘too much,’” Humphrey said. “There’s a lot of sexualization of girls in debate. Girls have to wear certain things to appeal to judges, whereas guys are fine. It’s just really annoying.”

Borgsmiller sits at her desk as the scene unfolds and students air their grievances. These ballots are nothing new. They only remind her of the times when she too faced the same stringent dress code standard that Humphrey does now.

“I can go even further back because I was a competitor myself. I started competing my freshman year in 1999, and we definitely had to fight it then,” Borgsmiller said. “I remember my coach was like, ‘you will wear this lipstick, and you will wear this skirt’ because you have to fit this role if you want people to even consider what you have to say. It’s not that she was buying into it—she was telling me that if I even wanted them to hear what I had to say to give myself a chance to win, I had to be a part of the expectations for females.”

The raucous din eventually fizzles out into milder conversation. Students disperse from their huddle in the center of the spacious classroom to a congregation of desks in the front, a pair of tables towards the back and an office room and supply closet lined along the far wall.

The next weekend–and the next tournament–is already on the horizon. Ahead of the quick turnaround, junior Kathryn McAuliffe is researching candidate privacy laws when her phone rings and a FaceTime request flashes across the screen. Just days before they are slated to compete again, one of her teammates is in a dressing room, restlessly searching for a skirt that would not be deemed too short.

“I can remember being nervous at tournaments about whether or not my dress was too short or if I raised my arms could you see my stomach when I should’ve been worrying about the argument I wanted to make,” McAuliffe said. “It’s another thing that girls have to consider for rounds that guys just don’t have to think about. It’s an added challenge to speech and debate. Instead of focusing on our arguments, intellect and experience, we have to divert energy away from that to make sure our knees or shoulders don’t offend anyone.”

Reviewing notes, junior Kathryn McAuliffe prepares for the MSHSAA speech and debate district tournament at Brentwood High School March 1.

The NSDA’s dress code guidelines instruct competitors to “dress in a way that authentically represents” them. Tell that to Borgsmiller, the 2019 James M. Copeland High School Coach of the Year, and a marked delineation emerges between progressive rhetoric and tangible action.

“Generally speaking, I don’t think a lot of [the NSDA’s] words have meaning because they don’t really back them up well. They say things like ‘dress to your authentic self,’ but then when you watch nationals and you see who’s on that stage, there’s no way that’s what those people look like on a daily basis,” Borgsmiller said. “You look at those girls, not only are they in a very expensive suit with jewelry, their hair is hairsprayed to the nines in a bun, pearls, caked on makeup, and none of that stuff has to happen with the guys. Part of the problem is the NSDA can say this, but then they put judges in the room and the judges make those decisions and that’s who they advance to these rounds. Those are the first things that are perceived about [female competitors] before they even open their mouth.”

‘The most annoying voices’

Reviewing notes, junior Kathryn McAuliffe prepares for the Greater St. Louis Speech Association Workshop Aug. 24. She finished ninth in Internal Extemporaneous Speaking at the 2019 NSDA Eastern Missouri District Tournament. “I’ve always prepared [for tournaments] knowing this bias is something I’ve had to deal with. Public speaking-wise, I always make sure I’m not loud when I speak, that I’m always controlled in what I’m saying so that I look very poised,” McAuliffe said. “That pays off so your judge isn’t judging you for being too passionate, and they can’t say that you’re outrageous in what you’re saying.”

At long last, the noise subsides and Borgsmiller has an opportunity to finish her lesson plans. She is teaching Human Communication, the first time the course has ever been offered.

An upcoming unit entails the study of voice quality, and as such, Borgsmiller peruses the Internet for video examples of various voice types to show her class.

“I was looking for the thin voice, a voice that resonates just in your mouth that doesn’t go in the chest or the nose. Everything that I found in that initial search was not an example of voice, it was articles about the most annoying voices that women have,” Borgsmiller said. “They were labeled as ‘horrible’ and ‘annoying,’ and that’s just the perception that people have. That thin voice has to be a female voice; it’s annoying, and we don’t want to hear it. That’s what I mean when I say I don’t think a lot has changed. That subconscious reaction to the sound of a female voice means you have to fight that more than a man does.”

Empirically, humans internalize deeper voices as stronger, thus more desirable and persuasive. From debate rounds to political elections, males hold a quantifiable advantage over females, not because of the words they say but the way they sound.

“When I’m debating against girls, my style definitely changes. I allow myself to be more passionate when I speak. If a girl’s really confident right before she’s about to compete, then she’s thought of as cocky, but if a guy is, he’s ‘assured of himself,’ so I’ve received a lot of comments after rounds,” McAuliffe said. “There needs to be more attention put on the fact that girls have a harder time in speech and debate and have a harder time being trusted. That impacts how girls perceive themselves even.”

Teri Quatman of Santa Clara University’s Department of Counseling Psychology and Education concluded that “boys significantly outperformed girls” in six out of eight aspects of adolescent self-esteem. All the while, Humphrey recalls numerous occasions of female voices rendered little more than punchlines.

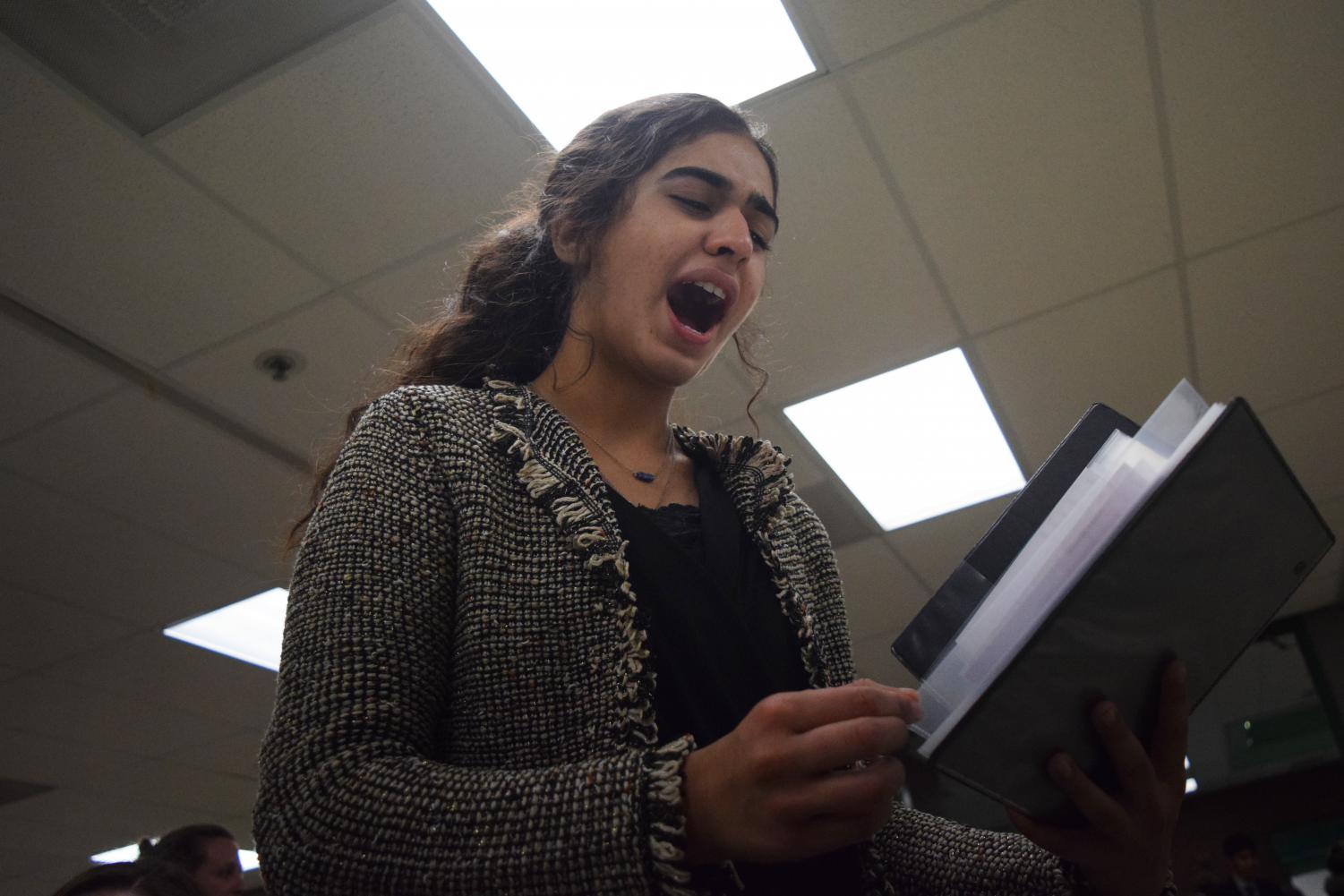

Alumna Kristina Humphrey rehearses prior to a round at the Greater St. Louis Conference Tournament Oct. 28, 2017.

“In [Humorous Interpretation], when I have to play a male character, it’s kind of funny, but when a guy plays a girl character, judges lose their minds. It’s the funniest thing they’ve ever seen because they can make their voice higher,” Humphrey said. “All of my sophomore year, all of my finals rooms were just guys and me. It was hard competing against that with the judges because they’re all like, ‘oh, these guys are so funny–and then there’s this girl.’ It’s just more expected because of sexism that guys are going to be smarter than girls, better debaters than girls.”

Junior Grace O’Connor, specializing in Program Oral Interpretation (POI) and Poetry Reading, recounts instances in which perceptions of her voice shaped the outcome of entire tournaments.

“With POI and poetry, since you have to have different characters, it’s all about playing around with characters. One of my characters was a person who just lost her mom to cancer, and I made her mad at the world. I got a comment that ‘anger doesn’t look good on you,’” O’Connor said. “That’s super disappointing to hear because people are allowed to feel anger, especially when they’re going through tragedy. A thing that really bothered me was there was a person in my round, and his piece was all about different emotions and how people cope with loss and the seven stages of grief. His character was extremely angry. He was yelling and storming around, and the judge gave him first in the room. When I was angry in my piece, it was seen as stupid and annoying.

“Girls can’t be too aggressive. You have to compromise what you want to say so that people view it as polite. That’s another challenge that women have in debate that men don’t. They don’t have to be conscious of everything they’re saying and their tone and their pauses. Whenever I talk, I only think about how I can make this sound polite so what I’m saying can be heard and not dismissed.”

Another day goes by–and the team moves another day closer to the next tournament. The afternoons to follow will bear witness to new strategies and arguments at practice rounds, but some old habits will survive well past this week.

“I will say that as a coach, I’m even guilty of doing the stuff that my coach in high school did, which is to tell my female speakers to find ways to lower your voice, to control the pitch and the tempo of your voice. You need to be passive and submissive in situations so that you don’t come off that way when the male debater that you’re going up against can do all of those things and be told that they’re being a great leader,” Borgsmiller said. “I also acknowledge that communication is a human activity, and you can’t change humans without first getting them to listen to you. Even though it sucks that you have to adapt to even get them to hear you, you have to do that first before you can start making a change and talking about what you want to talk about.”

‘They already trust the guy’

Junior Laura Young refines her speech after receiving feedback from teammates. Young and her debate partner, junior Zoey Womick (not pictured), placed second in the Greater St. Louis Conference in Public Forum Debate for the 2018-19 season. “Being a girl in debate is sometimes intimidating because when you go up against really good teams that are two males or even just one guy, they oftentimes have more of a reputation than the really excellent all-girl teams do,” Young said. “A lot of events are also male-dominated, which is also extremely intimidating because they come off as very charismatic and have so much more of a reputation that it’s just really scary to go up against them.”

The pandemonium of the preceding days has filtered into the type of ambience teetering along the fringes of awkwardness and romanticism that only a speech and debate tournament could provide. A line of competitors donning poorly-sized suit jackets and ties in dire need of straightening face directly towards an uninspiring wall in an equally uninspiring hallway.

In every crevice of the hosting high school, they restlessly scrutinize notes and complete last-minute rehearsal speeches before wading into otherwise empty classrooms. The high-budget wardrobes on display for the ensuing rounds are met with a setting that is anything but. Junior Kathryn McAuliffe scans the room before assembling a makeshift podium using a stack of textbooks she cobbles together. Both she and her opponent anxiously fidget while the judge writes their names onto the ballot and finally signals for them to begin.

Each side’s opening speech is accompanied by a three minute cross-examination period. It is, for all intents and purposes, a free-for-all. Debaters may use their three minutes to ask whatever questions they please. Some contentiously raise their voices in what quickly escalates to shouting matches while others, cornered by difficult questions, aimlessly ramble in hopes of stalling out the clock. It will be McAuliffe’s only opportunity to directly clash with the opposition, but she secretly dreads the experience.

“A lot of girls are aggressive and that can really affect their ballots. I never interrupt somebody even if they’re talking too long in cross-examination,” McAuliffe said. “I’ve been talked down to in the middle of rounds, so I’m not huge on cross-ex. I knew the questions were pointless because he was going to twist what I said anyways.”

Now, McAuliffe’s male counterpart presents his opening statement. Only, he addresses neither the evidence she cites nor the arguments she makes. Instead, he simply responds by claiming that she has a “basic misunderstanding” of the topic at hand to a slight nod of approval from the judge.

Junior Grace O’Connor prepares to compete in Poetry Reading at the Oakville Novice Events Round Robin Jan. 19, 2018.

“It just really hurt. Attacking the opponent rather than the case is a shoddy way to get out of an argument when you don’t have anything to say. It devalues the practice of speech and debate. We’re here to debate ideas, not to debate one another, and I don’t want to be called stupid,” McAuliffe said. “What’s inherently in speech and debate goes into what’s in our society because traditionally men have always been seen as the more political figures, and speech and debate is a political activity–they go hand in hand. You automatically assume that he is political, so I think, as a judge, you already assume that he has a command of the facts, and you’ll trust every single piece of information that he’s saying. By that point, you’re just evaluating the opinion. With inherent biases, they already trust the guy who’s about to give a speech more than girls.”

Borgsmiller has seen plenty of rounds similar to this one in her 12 seasons of coaching. Five years ago, a student of hers who would go on to win the MSHSAA State Championship in the Original Oratory public speaking event failed to even qualify for NSDA nationals with the same speech. She learned the harsh lesson that certain messages female competitors convey may fall on unwilling ears.

“Her senior year, she wanted to do a speech topic about how it was okay for females to be single, that they didn’t need to have a counterpart, typically a man, to define them. She ended up winning state, which was kind of a shock to all of us, not because she wasn’t successful, but because she wasn’t consistently successful,” Borgsmiller said. “Those people decided they wanted to hear her, but when we had our qualifying tournament for nationals, she got through three rounds and was straight [first place rankings out of six competitors], and then in round four, she had an all-male panel: got a five. Round five, she had an all-male panel, got a five and went out. There’s this line. You can say, ‘screw it–I’m going to say what I want, and say it the way I want to,’ and sometimes that works, but it’s definitely not going to work all of the time. I think that’s a perfect example of why that’s the case.”

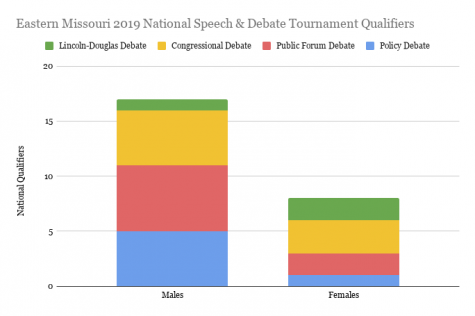

Of the Eastern Missouri district’s 25 qualifiers to the 2019 National Speech & Debate Tournament in Congressional, Policy, Public Forum and Lincoln-Douglas Debate, 17 were males to just eight females.

A chart displaying the Eastern Missouri district’s qualifiers to the 2019 National Speech & Debate Tournament.

“You have to work harder [as a female competitor], but I think that’s what makes it more satisfying when you do win or when you see that success or when you change somebody’s mind because you know you had to work three times as hard as the other guy, and you still beat him,” Borgsmiller said. “Perhaps at its core, that’s why it was so transformative for me, to feel empowered in that way and to know that I could make a difference despite the fact that I had to work a lot harder than other people had to. That replicates reality. The only way you can make change in the real world too is to change the hearts and minds of those that are on the ground.”

Yet in the face of these obstacles, the greatest act of resistance to sexism in speech and debate just might be females partaking in the activity.

“I think if we’re going to do this from a grassroots level, it has to come from more females participating and being willing to take the risks like my previous student was, which is hard to do because I think sometimes we want to win more than we want to make change, and that’s okay,” Borgsmiller said. “This is a group of teenagers. It’s super impressive that anybody wants to stand up and speak in the first place, but I just encourage more females to try this so they know that their voice can have power and make change.”

![Before the first round of the tournament, junior Grace O’Connor rehearses her Program Oral Interpretation (POI) performance at the Randy Pierce Winter Classic at Pattonville High School Dec. 7, 2018. Competitors create a performance using various published works of prose, poetry and drama around a central theme. “It hurts when people don't listen to your piece because you spend so much time working on it, and you do really pour your heart into it,” O’Connor said. “When people dismiss it simply because of your gender, it's so heartbreaking and for a lot of people it's not worth it [to continue competing]. It's not worth the emotional labor and the aspects of just not being heard because of what you look like or what your gender is.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/DSC_0008-900x600.jpg)

![Reviewing notes, junior Kathryn McAuliffe prepares for the Greater St. Louis Speech Association Workshop Aug. 24. She finished ninth in Internal Extemporaneous Speaking at the 2019 NSDA Eastern Missouri District Tournament. “I've always prepared [for tournaments] knowing this bias is something I've had to deal with. Public speaking-wise, I always make sure I'm not loud when I speak, that I'm always controlled in what I'm saying so that I look very poised,” McAuliffe said. “That pays off so your judge isn't judging you for being too passionate, and they can't say that you're outrageous in what you're saying.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/DSC_0030-1-900x600.jpg)

Victoria Araujo Alba • Jan 27, 2020 at 4:13 pm

Thank you so much for this article. Very insightful and truthful.

Katie Spillman • Sep 19, 2019 at 1:27 pm

So proud of the work you do. Big moment of pathfinder pride. Extremely well written and important content. Excellent work.

Kristina Humphrey • Sep 18, 2019 at 9:17 pm

IM CRYIN IN THE CLUB RN

Thank you for doing this Tyler, this article is incredibly well written. I’m missing you and debate a whole lot (even if it’s sexist)❤️

Shafiq khuhro • Sep 18, 2019 at 4:31 pm

Bravo Tyler! a brave article, I am proud of you.

Kim Hanna-West • Sep 18, 2019 at 2:20 pm

This is an important article. It’s time to expose and change the systems. Great work.

Susan Santhuff • Sep 16, 2019 at 3:36 pm

Very insightful article Tyler! Hope you take on the role as speech and debate judge some day!

Grace O'Connor • Sep 16, 2019 at 9:32 am

Thank you for writing this, Tyler. It means so much. ♡