Almost 70 years ago, on May 17, 1954, the landmark case of Brown v. The Board of Education was decided by the United States Supreme Court, deeming Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” notion as unconstitutional. Earlier, in 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson ruled that state-mandated segregation was not inappropriate, as the U.S. Constitution only protected citizens’ legal and political equality, not social equality. As a result, public spaces like hotels, movie theaters and water fountains were often labeled with signs that read phrases such as “Whites Only” and “For Coloreds.”

“Separate but equal” became a reference to Plessy v. Ferguson, yet segregation was anything but. Schools were also segregated by race, and in St. Louis County, Black students were bussed miles away from their homes for an opportunity to receive an education. Though many schools for Black students had an abundance of qualified, educated Black teachers, schools serving Black students still suffered from a lack of resources due to economic and social discrimination: many of their textbooks and educational tools were hand-me-downs from white schools, and Black teachers were not paid as well as white teachers.

Brown v. Board had established the unconstitutionality of de jure segregation with the hope of ceasing racial discrimination and ensuring minority students would be able to receive an equal education.

“Separate but equal” had ended, but any St. Louisan would be able to tell any outsider that this notion only ended nominally. Today, a history of largely-unresolved systemic inequities in both schools and their surrounding communities, as well as a wide berth in educational disparities across St. Louis, means that stepping into one school in St. Louis can feel like an extremely different experience than stepping into another school just a zip code away.

Despite the victory of Brown v. Board, the remains of St. Louis’s historic discrimination casts a shadow across the overall education system, coloring different realities for students across St. Louis.

Segregation and schools

In St. Louis, the notions of race and income are intimately intertwined, and it is no different when looking at how segregation in economics, housing and schools interrelate.

Historic racial discrimination caused vast amounts of segregation within St. Louis. Redlining was one of the tactics used to perpetuate segregation throughout the 20th century. Both private entities like banks and government-created political mappings prevented many Black families from being able to receive loans and move outside of designated areas. Neighborhoods occupied by Black and immigrant families would often be marked in red, hence the term, to denote housing with minimal value.

Individual voters would contribute to housing-related discrimination as well, showing general support for institutional practices but also passing a 1916 ordinance that prohibited the movement onto a block where three-quarters of a block’s population was another race than the person desiring to move houses. Challenged by the NAACP in judicial court, this ordinance would later be replaced by racially restrictive covenants.

Real estate developer-written covenants that prohibited Black, Asian American and Jewish communities from purchasing and owning houses in certain areas also heavily contributed to segregation in St. Louis. It was only in 2022 — when Missouri Governor Mike Parsons signed legislation that banned discriminatory language that, while legally unenforceable, still existed in many home deeds — that racially restrictive covenants were officially required to be removed.

With housing discrimination, racism and classism often went hand in hand. Keeping Black and lower-income families from buying houses outside of designated areas was only a continuation of the rampant systemic inequities designed to benefit white and wealthy communities and disenfranchise minorities and low-income communities in St. Louis.

In the 1948 Supreme Court landmark case Shelley v. Kraemer, the legality of racially restrictive covenants was challenged, and the enforcement of racially restrictive covenants was declared unconstitutional. Though the ruling intended to halt unjust housing discrimination, the prohibition of such tactics sparked a period where the white population fled St. Louis City to the suburbs, commonly known as “white flight.” Many middle-class Black families soon followed. With them, they took much of the economic prosperity and tax base, leaving behind the historically economically disadvantaged communities.

Though steps like the Fair Housing Act were taken to reduce housing discrimination in the mid-20th century, schools across St. Louis were still both separate and unequal, as shown by the fact that 90% of Black children were still attending predominantly Black schools in 1980, nearly 30 years after Brown v. The Board of Education. Redlining and racial restrictive covenants, though deemed illegal by the 1960s, effectively confined Black families into specific neighborhoods, resulting in de facto school segregation. The pattern of “white flight” led to white families building wealthier districts with their money, leading to schools with more resources; meanwhile, the sudden mass exodus strained resources in schools where most economically disadvantaged Black communities lived.

While Brown v. The Board of Education forced racial segregation to stop in schools, it did not stop the racist mindsets that caused the cycle of the disenfranchisement of the Black community in the first place — instead of working to bridge the gap between the different communities in St. Louis, school district boundaries were often re-mapped in an effort to maintain distinctly white and Black neighborhoods.

The effects of racial segregation in the 20th century can still be found today. In 2020, St. Louis was ranked #10 in a list of the Most Segregated Cities by Berkeley University, which noted the segregation level as “high” in categories of high, low-medium and integrated. Aligning with the high concentrations of segregation in St. Louis was the distinct gap in economic development in the region.

“Economic development, of course, brings funding into the district. That is a big barrier that Riverview [currently] suffers from,” St. Louisan youth advocate, current Washington University freshman and Riverview Gardens High School alumna Precious Barry said. “Coming from a district that didn’t have a lot of economic development in the community, we didn’t have a lot of outside resources funding our school district [which can] lead to a community of poverty.”

In order to bridge the gaps created by this historical segregation in the 1970s and 1980s, there were efforts to force racial diversity into school systems by way of desegregation programs. Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for Parkway School District and Parkway parent Dr. Cartelia Lucas attended Rockwood School District through a desegregation program — which would later be renamed the Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation — beginning in fourth grade.

“My mother was very invested in education. At the end of the school year, [my mom] would make us dumpster dive — because the school would throw [school materials] away — so we could do school over summer,” Lucas said. “Well, that particular summer, she got a hold of a standardized test, and she had us take the test. Around third grade, some of my cousins started the deseg[regation] program [and they] did all of the tests and got most of it right. In the city schools, I was a straight-A student, [but] what happened on that test was the [catalyst] where [my mom] was like, ‘Absolutely not; my kid needs to go in this program.’”

The primary desegregation program in St. Louis, the VICC program, intended to send students from predominantly Black, inner-city schools to predominantly white, suburban schools and vice versa. However, most students would be coming from predominantly Black school districts due to classism and racism, along with the fact that school districts serving majority-Black student populations in St. Louis were majorly underfunded compared to their predominantly white counterparts. To be clear, when comparing these statistics, it’s not necessarily correlation — Black students are not intrinsically linked with low education — but rather causation: the racial discrimination against Black people economically, socially and educationally has caused a profusion of educational inequities.

Though there has been an effort to diversify schools in the suburbs, with 765 students coming from St. Louis City to Parkway through the VICC Program, the number of students who are bussed to the city — nine students, who attend top public high schools in St. Louis City — pales in comparison to Black students from the city coming to the suburbs. With the elimination of the VICC Program, many people are finding that St. Louis is in a very similar place to the 1980s — low rates of diversity and underfunded schools.

In short, St. Louis’s education system as always been deeply flawed when looking at race and wealth, so the current segregation and underfunding of schools in St. Louis is far from a new phenomenon.

Current inequities across St. Louis

One of the barriers in the education system in St. Louis is the sheer inconsistency of the continuation of education depending on where one lives. Having previously lived in St. Louis City and sending her daughter to Mason Elementary for preschool, social studies teacher Kristen Collins found herself with a conundrum that many other parents in St. Louis face.

“My daughter loved [Mason], and she learned so much. My bigger concern was with what was going to happen once [Lucy] hit middle school and high school. I wanted continuity for my daughter and her schooling, where she was going to be in the same district with the same kids throughout [her years].” Collins said. “I didn’t want that pit in my stomach [when] she reached sixth grade wondering where she was going to go or whether it would be good. I wanted a sure thing. I didn’t want to gamble with my kid’s education.”

For kids who are not labeled “gifted” by the education system, there is often uncertainty concerning the quality of education a student may receive, which causes discord for parents seeking to continue their children’s education beyond preschool and elementary school.

There’s also the difficulty of many St. Louis-area schools facing consistent disparities in resources, classes and demographics — some of which are visible in the exact same district. Many of these imbalances stem from St. Louis’ historic segregation that stripped resources from the primarily-Black communities of St. Louis. These discrepancies have continued to today, where many students in St. Louis face a lack of resources, a lack of diversity and a lack of widespread, system-spanning change.

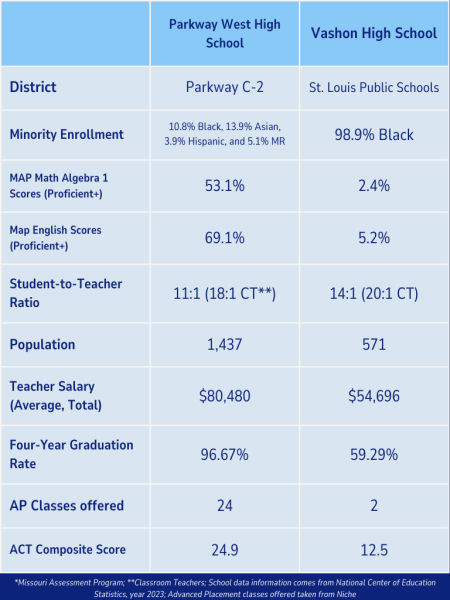

To further examine the ingrained disparities between predominantly white and predominantly nonwhite school districts in action, this chart compares the current differences between Parkway School District’s West High School in Ballwin, MO and a high school from St. Louis Public Schools in St. Louis, MO.

(Elizabeth Franklin)

The disparity shown in this chart is not a unique situation. When traveling from zip code to zip code, there’s a wide berth in AP classes offered, median house value, graduation rate and average teacher salary when comparing schools in the St. Louis Metropolitan area.

Rigorous and proven to prime students for college-level coursework, AP classes are currently essential to students who want to push themselves academically beyond on-level curriculum. Though colleges will take the rigor level offered at schools into account when making acceptance decisions, it’s understood that taking AP courses can generally increase the chance of college acceptances and degree acquisition. However, Black students continue to lag behind in AP enrollment — not only in St. Louis or Missouri, but across the country — which not only sets a gap in academic challenge, but a gap in opportunity. Even Parkway has a gap in AP classes, which is reflective of how history still contributes to the massive educational disparities today.

In addition, school districts with predominantly white students are, on average, wealthier than school districts serving predominantly nonwhite students. This means that school districts with primarily nonwhite students are spending less money per student and that means less money is spent on necessary resources such as school supplies, building maintenance and teacher salaries.

Today, Missouri ranks among states receiving the least amount of state funding for education, meaning that most of a school district’s funding in Missouri is accrued from local sources — namely, the community surrounding the schools. For wealthier St. Louis-area school districts like Ladue, property taxes contribute to their large — in proportion to their relatively small student population — operating budget and access to premium, quality resources for schools. For other school districts whose property values are worth less, however, this can mean a much tighter budget to work with.

“When you’re underfunded, you only have the money for the necessities — just like in a home. [If] I don’t make a lot of money, there’s no going to Six Flags or eating out every night — it’s only the bare minimums. When we think about a school, if you’re underfunded, it’s the bare minimum,” Lucas said. “We start to cut the arts programs. We don’t have the funds for development in a way that we probably need, the funds for extracurricular activities, for social-emotional support. All of these things that, in my opinion, we at Parkway are extra blessed to have and take for granted [because] it’s what we know. Many schools that don’t have that, [which] perpetuates the inequity.”

As a result of less funding, teachers are paid less at schools with a nonwhite majority, which drives many more teachers to predominantly white schools, where they would be paid a much higher rate than at nonwhite schools in St. Louis. On average, teachers are already paid around 25% less than their peers who went through similar education; the disparities in pay between high-income and low-income districts and areas dictate which districts teachers may flock to.

“There’s a big disparity in the quality of teachers and [how much] teachers [are] paid. Teachers jump ship from schools with lesser pay and try to come to school districts like Parkway or Pattonville or Clayton because they pay better,” Collins said.

The size of a school district matters, too. Districts that are smaller and wealthier — like Clayton School District, which served 2,443 students in the 2022-2023 school year — retain a fewer number of students, which means they can spend more money per student. On the other hand, school districts that have over 10,000 students like Wentzville School District, Rockwood School District and Francis Howell School District must spread resources over a wide array of students. Many larger districts may not see substantial inequities on the district level but may see inequities in individual schools and their teachers and classes.

As a whole, inequities can be seen in the amount of resources that may not be available in schools unable to spend as much money per student.

“[A student at Parkway] has the opportunity to be at a school [where their] teacher doesn’t have to worry about how many pieces of paper they print on. They’re not given two reams of paper for the year. That still happens in some districts — you got to make it happen with two reams of paper. If a teacher is worried about two reams of paper and doesn’t have [many] resources, as a given, [a student is] going to have less opportunity,” Lucas said.

Another inequity pertaining to teachers involves chronic teacher absenteeism, or how often a teacher is absent from the classroom. Studies have shown that a teacher’s attendance affects their students and classroom: chronically absent teachers disrupt the flow of the classroom, the materials being taught and the efficiency of the class overall. Generally, schools with higher amounts of poverty see more chronic teacher absenteeism.

Schools across St. Louis faced this problem at even higher levels following the COVID-19 pandemic, though consistent teacher absenteeism has been a problem for decades. In 2018, St. Louis City found that Black students were more likely to be present in schools that had a higher percentage of chronically absent teachers.

In addition to teacher absenteeism, there’s additionally an inconsistency among teachers in lower-income schools and districts. Teach for America is a nonprofit organization that aims to develop educational equity by recruiting highly qualified college graduates to teach in low-income schools; however, there is one issue that currently plague the organization: a high staff turnover rate. High turnover rates among school faculty cause adverse impacts on student achievement, particularly in low-income schools, which catalyzes a cycle where the ones who are in need the most resources are not able to get them.

Furthermore, it has been illustrated that socioeconomic factors play a significant role in the development of foundational reading, writing and math skills as well as overall — K-12 and post-secondary — educational success. From the number of libraries to which a child has access to the availability of hands-on opportunities and experiences, there are countless factors that contribute to the overall quality of a student’s education.

However, in low socioeconomic households, there are numerous stressors that can be inadvertently placed upon a child, such as community and/or family violence, lack of nutrition in the home and financial crises — all of which cause poverty-related trauma. While not all students who are of low socioeconomic status suffer from all or even one of these issues, the students who do endure these stressors can develop behavioral issues, which have the possibility to cause enormous impacts on their mental health and subsequently, their school life.

Though these stressors can cause issues for students, in schools that do not receive as much funding, it is significantly more difficult to fund resources that deal with social-emotional wellness, like well-qualified counselors or organizations who could potentially aid with common stressors and behavioral issues in poverty-stricken communities like homelessness, inconsistent education associated with frequently changing schools, and living in areas with higher amounts of crime and/or violence with rates consistent with lower-income communities and large cities.

“I think some of our legislators don’t see it in a bigger picture. It’s not connected. [They see it as] school is a place for reading, math, science and social studies. And you should be able to do that with [a set] amount of money. Well, [a student] can’t engage in reading, writing, math and social studies if [their] basic needs aren’t met; if [they’re] not safe or secure; if [they] don’t feel connected. Those are all things that the extra funding helps us with,” Lucas said.

In addition, particularly in areas with high levels of economic strife, students are more likely to drop out of school to support themselves and their family. This economic strain can be seen in many schools’ attendance rates as well as the amount of crime in certain areas.

“Coming from a district that has a [lower] attendance rate, a lot of our students are not in schools. You also have a community that has [99%] of students that are eligible for free [or] reduced lunches, so we have a majority of our district [being] working-class families,” Barry said. “[In the community], you have parents that are working 9-to-5 jobs, you have students that are probably working 9-to-5 jobs just to put food on their plates, clothes on their backs and roofs over their heads, so they can make it to the next day.”

Currently, the quality of education a student receives in St. Louis is based on the zip code from whence they come. Since zip code determines the school district and individual school a student attends, where a student lives can also determine educational results like ACT scores and future degree attainment as well as future life aspects, like job growth and social mobility.

“No matter the numbers of a person’s zip code, everyone deserves quality education,” Barry said. “[We are trying to] make sure that our school districts, our community leaders and our elected leaders come together and figure out solutions. How can we have young people going down the right path — when it comes to resources, when it comes to family support and when it comes to necessities — to help them grow and elevate and reach their next level in their academic journey?”

Lucas believes that a common error people make is assuming that historical economic discrimination only affects schools with tighter monetary budgets, but she argues that simply isn’t true. Inequities are not just an issue because of the race or income of the people affected — it is an issue because there are human beings trapped in a cycle of an inequitable life due to historical discrimination. The impact of inequities does not just affect students who have unequal access to resources or teachers who may be underpaid, but the entire surrounding communities.

“We, as a nation, lose money, because of [unequal education]. Diversity is profitable. If businesses want to look at a business model, you gain more by having diverse, equitable places. Not that that’s the only reason to do it, but for people who are so stuck in their ways and like to look at it from a business standpoint — [equity] helps you promote business,” Lucas said. “As far as the impact of the continued inequities, it costs money when we aren’t able to educate our children. It cost us tens of hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Educational inequities contribute to community inequities and vice versa. The systematic design of St. Louis’s systemic discrimination and economic inequities echo the numerous disparities that are ingrained in the school districts across St. Louis.

“I always joke that I teach in the ivory tower; Parkway West is a really good school. We have really good kids here, but there’s also great, smart kids in North City. There are really great, smart kids in North County and South County and St. Charles — everybody has that potential and I think if you could pick any of those kids and plop them here, they have the potential to do really well,” Collins said. “But the quality of education [and] access to resources isn’t the same at all.”

The future of education in St. Louis

For years, education in St. Louis has been a hot-button issue, but disagreements on how to handle overall systemic inequities have persisted. Furthermore, living in a capitalist society influences the difficulty of funneling higher-income taxes to lower-income schools without major structural changes.

Many education advocates believe that revamping the education system is a worthwhile issue since the impacts of an inequitable education can contribute to generational wealth, which has an impact on overall life earnings. In fact, one of the aspects that can supply a higher level of generational wealth comes directly after high school: post-secondary options like college or technical education. These are opportunities that can be derailed by the inequities in a systemic education structure.

Low-income schools affect every race across the country, but in St. Louis, the effects of segregation continue to have negative effects on particularly Black students’ education.

“Educational disparities make it difficult for people to go to that next level in high school — whether that be with the lack of the support system or lack of a college and career professional working with them at different schools or different places,” English teacher Casey Holland said. “And maybe the school isn’t prepared enough to help them to get to the next level, so it’s all just kind of like a perfect storm to not help [students] to succeed.”

To deter this disparity, beginning in 1961, systems of affirmative action were often used and designed to implement measures to take steps toward a level playing field for historically disadvantaged communities — which did not just include Black students, but other racial minorities and women — especially in schools. However, with the 2023 Students for Fair Admissions v. President And Fellows Of Harvard College decision that struck down affirmative action, race-conscious admissions have been overturned. This decision has concerned many, including Lucas.

“If I was working off of my credentials from a senior in high school, and there was no affirmative action, I probably would not have been accepted into college. That sinks in for me because I am still the same person with the same capability and the same ability then, that I am now. It’s just the opportunities are different,” Lucas said. “I don’t get to be Dr. Lucas if there was no affirmative action, and I couldn’t get into a college because the experiences that I had — from early education up to high school — were the resources that were supposed to be helping me learn. And those are the inequities that can potentially impact any child based [on] the perception of what their abilities are.”

Still, Holland — who also serves as a principal for the Maryville College Admissions program in Parkway — believes that there’s work that can be done to counteract the effects of past iniquities for current students seeking higher education, and it begins with administrative change.

“One thing that we’ve seen lately, especially since the pandemic, is a more holistic review of students [applying to colleges]. I know a lot of the schools that I work with in the summer have gone test-blind or test-optional, so they’re looking at the whole picture of a person and so that’s one way to kind of combat these inequities [in admissions],” Holland said. “[At the high school level], we need to make it a point to have [college] conversations early with students. It starts with a great counseling team and great staff [and having] good relationships with those students to help them reach their goals and their full potential.”

Though continuing programs to advance diversity in post-secondary education is essential in ensuring equitable education, rapt attention toward elementary, middle and high schools systems is equally important. Collins proposes a free, enriching, comprehensive preschool program for all schools — something that many districts, including St. Louis Public Schools, have made an effort to do in recent years.

“I think that one of the biggest things [schools can do] is [provide] access to quality pre-K. St. Louis City has this really amazing, very progressive, free pre-K system. You apply and there’s a lottery not to get in, but to go to the school,” Collins said. “You could go to any [school] but they have a cap on how many students are allowed to attend each school. Mason was my neighborhood school and it was also considered to be one of the best.”

Currently, there are 90 private preschools in St. Louis and several Early Childhood Development centers and programs in districts like Fort Zumwalt School District, Ritenour School District and Mehlville School District. High-quality preschool programs have demonstrated benefits for students before they begin kindergarten, like a strengthened vocabulary and critical thinking skills. Attending preschool before kindergarten can also substantially improve chances of success during later student and even adult life. Besides generally serving advantages for the general student population, quality preschool programs are even more valuable for kids who may be economically disadvantaged or live in areas with underfunded schools.

“So many of those kids are grossly behind when they’re 5 or 6 years old,” Collins said. “I think that St. Louis [Public] Schools did make a big, really important move to try to improve their schools by offering pre-K to 3, 4, 5-year-olds. [Pre-K] is a big cause that I wish more people would try to jump on because I think it does help a lot.”

Both Lucas and Barry also note community engagement as a potential long-term answer. Mentorship programs, like Mentor St. Louis, partnered with the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater St. Louis and the Spire Energy mentor program have been implemented in some St. Louis-area schools in the past. Barry believes that the implementation of such programs is essential for students’ esteem and self-confidence.

“[A] way that we can fix our education system is [by] bringing more mentors into different school districts [who believe] that, no matter a person’s background, it doesn’t define their future. There’s so many people in the community who have been through a lot, turned their life around and have a story to share,” Barry said. “Imagine if we have all of those people coming into districts like Riverview Gardens, like St. Louis Public Schools and other districts that may have inequities in it, speaking to those scholars [saying], ‘Hey, I’m here, I’ve been in your shoes before, and I want to help and I want to be that bridge, I want to make sure that you have this support.’”

Furthermore, Lucas argues that student mentorship from business leaders could potentially close gaps in education and resource disparities. Parkway North alumni Sylvester Chisom is the co-founder of the Show Me the World Project, a hands-on organization that collaborates with students in under-resourced communities to promote science, technology, engineering, math and entrepreneurship competencies.

“[Show Me the World] provides youth from under-resourced communities life-changing educational experiences at home and abroad. [A student] runs a mission-based coffee business and [learns] how to use coffee as a teaching tool. The kids are learning workforce readiness skills; they’re learning important global skills that companies are looking for [like] communication, collaboration, teamwork and critical thinking,” Chisom said. “Our students are going to college to study STEM careers and learn how to operate coffee businesses, as well as their own businesses. We’re really preparing them with the educational tools that set you up for future economic mobility.”

Through the Show Me the World Project, students are not only presented with mentors who teach comprehensive skills about the real world but also hands-on, experiential learning. This learning includes trips to Costa Rica, where they learn how their coffee is made by exploring the jungles and rainforests, giving them experiences that will stick with them throughout their lives. This project-based learning has, by Show Me the World Project’s admission, increased a majority of students’ biology grades and overall GPAs.

“He’s teaching [students] skills and giving them opportunities to access resources to not only make a difference but to travel. That’s a partnership with a corporation that is benefitting lots of kids’ learning skills [through] traveling, marketing, selling. You can’t teach some of that stuff from a book — those are lived experiences. [Chisom] is putting his money where his mouth is,” Lucas said.

When considering all of the options to implement such measures in schools across the metropolitan area, the cost to fund such programs would be expensive. However, Lucas urges both the state government and businesses to invest in schools and mentorship programs; she believes that their help is essential to the future of equitable education.

“It’s ironic because Missouri is the ‘Show-Me’ state. Well, show me the money. [Corporations should] put their money where their mouth is. Fully fund education. We have corporations that spend millions of dollars lobbying for various things — this is how businesses and politics [work]. You pay lobbyists to lobby for different things, start paying lobbyists to lobby for education. That’s putting your money and your privilege, as an entity, where your mouth is at,” Lucas said. “I think [if] we can get partnerships with corporations and power players that have the funds to [pay for] those [programs], we could have change [area]-wide.”

Most education advocates maintain that no matter the location, no matter the zip code, each student who walks into a classroom deserves to have the same opportunities as their peers when it comes to education. In the end, it is vital for communities across St. Louis — varying in socioeconomic status, race and perspective — to all step forward and be a part of the conversation.

“I’m not here to call you a racist, I’m here to say everybody needs quality education. [Students] need to feel safe in school, [students] need to have opportunities that allow [them] to have a quality education. [We should seek] coalitions, where we are all working together for a common goal,” Lucas said. “Within inequities, no matter whether we’re talking about race, gender [or] socioeconomics, people have to be engaged in conversations that call them in and not call them out; conversations that push them to reflect on their beliefs.”

Dr. Annie Miller • Feb 19, 2024 at 3:43 pm

Excellent article Elizabeth. Keep helping others understand the important issues. Knowledge is power!

Monisha • Feb 14, 2024 at 7:40 am

I’m so impressed by the level of research that went into this article. Very good writing. The comparison chart showed everything we needed to know and I hope action is taken.

Dr. Piffel • Feb 13, 2024 at 11:36 am

Elizabeth, I continue to be in awe of you, your work, and your willingness into the “messy” topics. Thank you for sheading light on this topic for others to hopefully understand!

Danielle Belton • Feb 13, 2024 at 6:37 am

So well-written and has such excellent reporting and research! I see a bright future here!

Crystal • Feb 11, 2024 at 3:20 pm

Wonderful insight and accurate information! Love the article.

Lauren Holcomb • Feb 9, 2024 at 6:00 pm

this is so interesting, this issue is definitely under-reported! i gasped at the comparison between Pwest and Vashon, Missouri has such a problem with class and racial segregation.

Will Gonsior • Feb 9, 2024 at 2:11 pm

Ms Lucas was my principal back in the day. Not a name I have heard in a long time lol. Thank you for the excellent article Elizabeth!

Emily Early • Feb 9, 2024 at 1:37 pm

Elizabeth, you can tell just how much work went into this article — you are a fabulous reporter. Thank you for bringing attention to this subject!