The model minority myth characterizes Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) as a successful, prosperous, intelligent monolith, capable of anything and subject to equality. It’s characterized as a myth, however, because this single story has been and is still used to cover up and soften injustices against entire peoples. Even in our schools, the model minority myth permeates the education system and perpetuates AAPI racism, and the time has long passed for things to change.

The history of the model minority myth

In the nineteenth century, Chinese immigrants who came to build the transcontinental railroad were tortured and abused as they were accused of stealing white men’s jobs and for being the cause of the U.S.’s economic downturn. Former President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 ordered Japanese Americans to internment camps following the Attack on Pearl Harbor. For years after 9/11, Southwest and South Asian Americans faced open violence and discrimination in their daily lives. Now since the onset of COVID-19, hate crimes against AAPI communities have risen 150% in the last year, including racially-motivated murders.

In the aftermath of the internment camp crisis, Japanese-Americans were lauded for their resilience to injustices in comparison to African Americans, so white Americans could absolve any blame for the perpetual dehumanization and systemic racism committed against Black people: people pointed to Asian Americans as an example of minorities who were able to succeed despite racism, and deemed African Americans simply incapable of it.

This ignores the distinct difference in the racism faced by both groups. While Asian Americans were met with immigration bans, citizenship issues, incarceration camps and many more examples of prejudice, Black Americans have been subject to enslavement, segregation, police brutality, and countless other forms of overwhelming discrimination. Both groups have faced gruesome racism, but Black people were specifically dealt certain kinds of deep, structural setbacks.

As a result of the ongoing narrative of Asian Americans’ ability to overcome the prejudice they face in the United States, the group began to gain a little more respect from white people than their Black or Latinx counterparts, meaning they were able to receive more opportunities for advancement than these other groups.

AAPI are shuttled between being considered an idealized group and facing gruesome violence and calls back to reality. This shuttling widens the gap between two major, current racial inequality movements in our country.

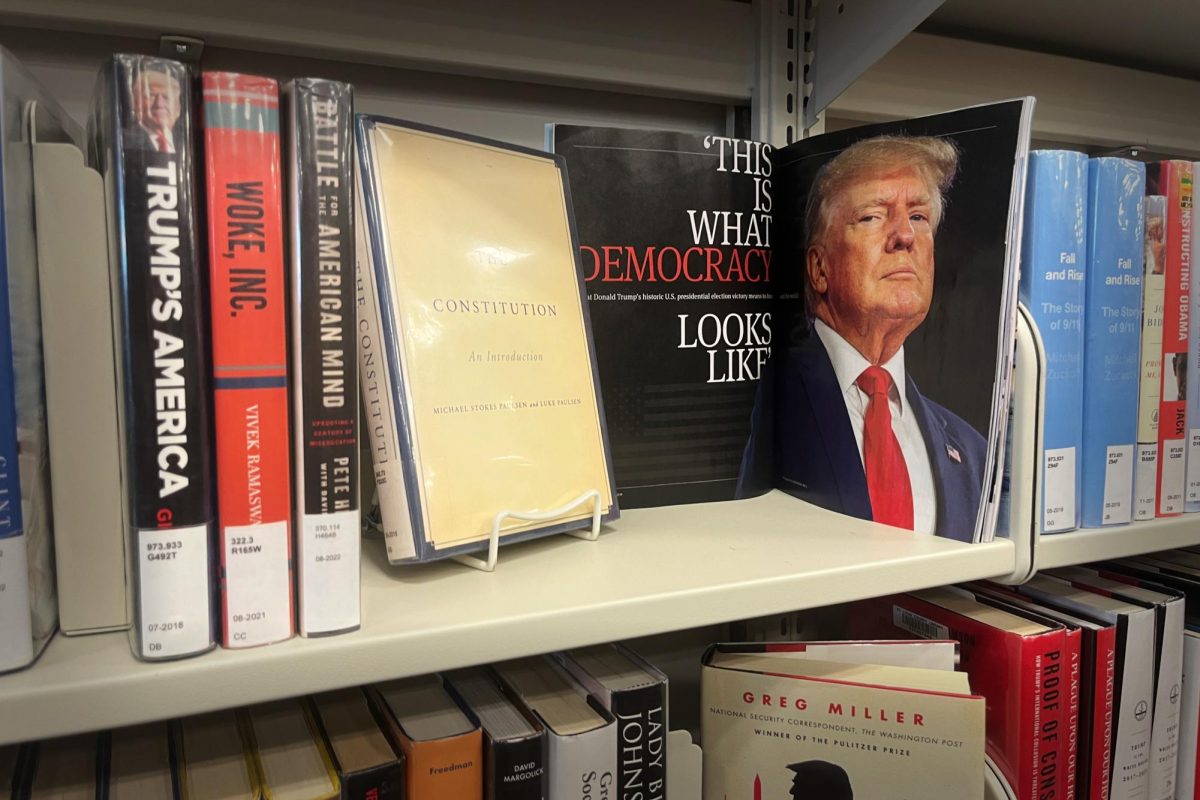

New York Magazine published a prime example of this just in 2017. Andrew Sullivan summed up his piece “Why Do Democrats Feel Sorry for Hillary Clinton?” with this clincher intended to prove that American society is not racist:

“Yet, today, Asian-Americans are among the most prosperous, well-educated, and successful ethnic groups in America. What gives? It couldn’t possibly be that they maintained solid two-parent family structures, had social networks that looked after one another, placed enormous emphasis on education and hard work and thereby turned false, negative stereotypes into true, positive ones, could it? It couldn’t be that all whites are not racists or that the American dream still lives?”

This idealized single-story has been weaponized as a means to draw attention away from the true racial injustices rampant in American society. For AAPI, this myth can be used to provide a false sense of comfort between violent wake up calls.

Current effects of the model minority myth

Today, the effects of the model minority myth are still in full swing, negatively impacting both Asian American and Black communities.

The model minority myth is detrimental to Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders that live in poverty. Because Asian Americans are perceived as incredibly successful despite anti-Asian racism with high educational and occupational achievement, it’s often ignored that Asian Americans are also the lowest group on the poverty ladder, especially Asian American women.

By ignoring the fallacies of the model minority myth, policy-makers don’t acknowledge the racism and sexism that results in lower income for Asian Americans and Asian American women, giving them less opportunities in employment, healthcare, education, and other issues which contribute to poverty.

The perception of Asian Americans as hard-working but submissive decreases chances of promotion in management and leadership positions, causing these communities to prioritize work over recognition and speaking out against misbeliefs.

Instead, Asian Americans are more likely to be promoted or given a leadership position during a crisis or when the company starts to deteriorate, due to the belief that Asian Americans will make personal sacrifices and work hard despite adversity in order to benefit the company.

Due to the dissociation between Asian Americans and other racial groups, they are forced to choose between being continually regarded as foreign or allying themselves with either Black or white people, the latter often being the case and fostering anti-Black sentiments in AAPI communities.

As a result, Black communities experience increased poverty, police brutality and oppression, with a smaller amount of people receiving benefits or living in integrated neighborhoods in comparison to Asian Americans. Setting Asian Americans and Black people against each other marginalizes both groups’ struggle for equality and increases the abuse and exploitation of minority groups.

The model minority myth and the education system

The roots of this myth also grow from our education system. Jan. 9, 1966 William Peterson published “Success story, Japanese-American style” for the New York Times, an in depth feature about how the traditionalist values of Japanese-American immigrants– obedience, quietness and dedication– played a major role in their academic success and relatively seamless integration into American society.

Peterson reduced an entire race, and entire people, down to just a few traits: this reduction is the reason that even today, racism against AAPI exists.

The education system perpetuates the oscillation between the idyllic image of an immigrant fabricated by model minority myth and jarring reminder that they’ve been the scapegoat for an entire country’s systemic issues.

In schools, honors and Advanced Placement courses on average have much higher proportions of Asian American students to white students or other minorities, and overall perform better on the standardized tests. According to the College Board’s 2020 National AP Report, students who self-identified as Asian scored an overall average of 3.43, followed by those who identified as White at 3.09, with Hispanics and Latinx-identifiying students scoring 2.67, Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander-identifying students scoring a 2.64, Native American-identifying students scoring a 2.57 and Black-identifying students scoring 2.32.

This solidifies the misconception that AAPI are inherently better than other minorities, which only serves to put Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in a rigid box, ignoring the struggles they’ve faced in this country, and then paint other minorities as inferior and unable to succeed.

It is our responsibility as an education system to teach how the model minority myth covers this up, to teach all racial inequities in our country and how we’ve historically used them to manipulate peoples.

As an education system, it falls on us to be aware of and address the real issues the myth of the model minority covers up: According to a 2010 Education Trust-West report, by the end of high school “roughly 7 out of 10 Asian students and 9 out of 10 Pacific Islander students are not prepared for college-level coursework.” Statistics like the National AP Report above show only a select fraction of the entire AAPI population. There are many more AAPI students who don’t have the resources to be able to take such tests, and the model minority myth muffles the urgency of that problem.

We need to ensure AAPI students have access to resources they need to succeed so they have the opportunity to break the systemic cycle of disinvestment and poverty. We need to look beyond numbers that only tell half the story, beyond misconceptions and single stories.

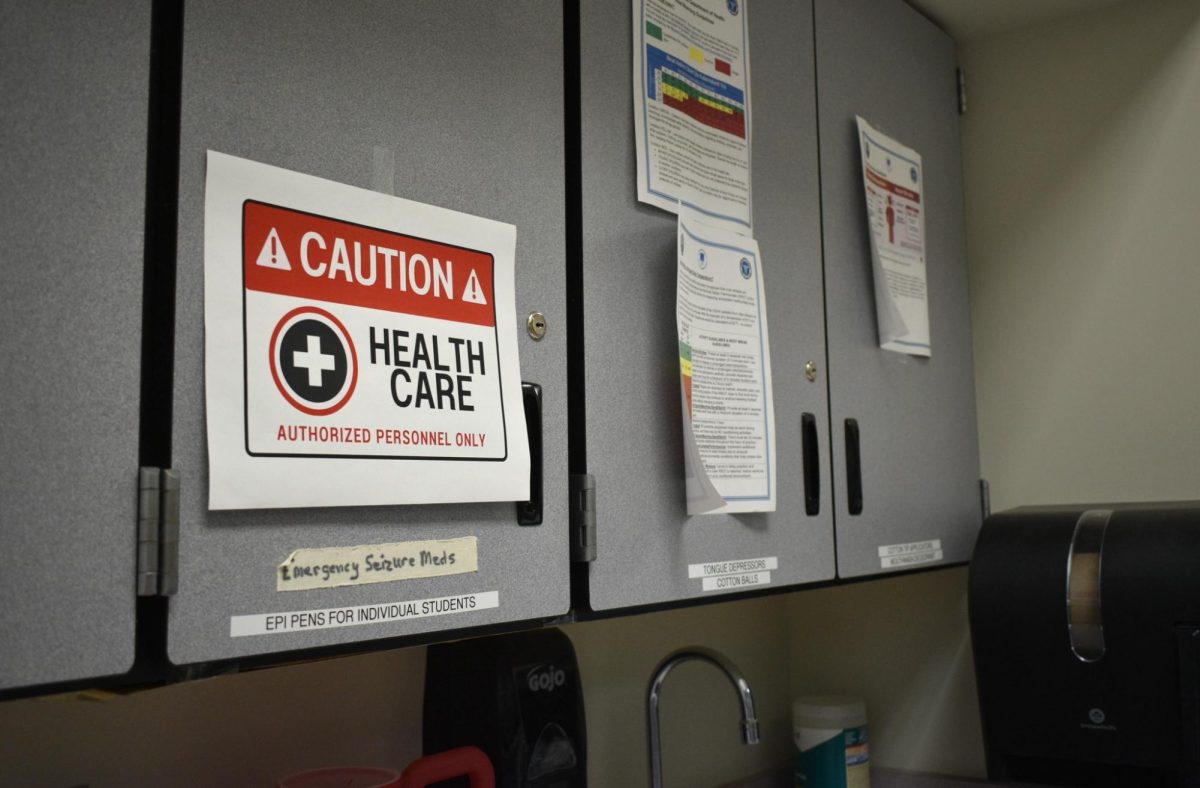

We need greater accessibility to English as a Second Language (ESL) and other support classes, to mental health resources and treatment, to information on the history of discrimination and manipulation. Only by acknowledging our collective past mistakes can we learn from them and step forward into a brighter future.

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Red, white and blue, the American flag holds the values of our democracy. The fight that we once endured has returned, as student journalists and senior correspondents across the country are losing their voices due to government control. “[Are] the White House and [the] government limiting free speech [and] freedom of the press? Yes [they are],” chief communications officer of the Parkway School District and former journalist Elisa Tomich said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Untitled-design-14.jpg)

![A board in the Parkway West counseling department displays pennants of selective universities. With a wide range of students interested in attending, it’s important that these schools have clear priorities when deciding who to admit. “[Washington University] had the major that I wanted, psychology, philosophy, neuroscience. That's a holistic study of the brain, and [WashU is] the only college in the world that offers that. That's the main reason I wanted to go; I got into that program,” senior Dima Layth said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Flag-1.png)

![Within the U.S., the busiest shopping period of the year is Cyber Week, the time from Thanksgiving through Black Friday and Cyber Monday. This year, shoppers spent $13.3 billion on Cyber Monday, which is a 7.3% year-over-year increase from 2023. “When I was younger, I would always be out with my mom getting Christmas gifts or just shopping in general. Now, as she has gotten older, I've noticed [that almost] every day, I'll open the front door and there's three packages that my mom has ordered. Part of that is she just doesn't always have the time to go to a store for 30 minutes to an hour, but the other part is when she gets bored, she has easy access to [shopping],” junior Grace Garetson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/DSC_0249.JPG-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Sally Peters stands in the history hallway, contemplating her choices in the 2024 United States and Missouri elections on Nov. 5. As a member of Diplomacy Club, Peters has discussed key candidates and issues in contemporary American politics. “[As students], we're starting to become adults. We're realizing how much the policies that are enforced and the laws that make it through the House and Senate are starting to affect us. [Opportunities such as] AP [U.S.Government] and Diplomacy Club [make elections feel] a lot more real,” Diplomacy Club vice president and senior Nidhisha Pejathaya said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Flag-1-1.png)

![Mounting school pressure can leave many students overworked and overstressed. Schools must give students the necessary resources to help assuage student mental health issues and prevent the development of serious crises. “The biggest thing [schools] can do [to protect student mental health] is offer more time [to do work], like a study hall, or offer more support from teachers so that students don't feel stressed out and can get help in areas that they need,” senior Bhavya Gupta said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/unnamed-4.jpg)

![After a thrilling point, senior Katie Byergo and junior Elle Lanferseick high-five each other on Oct. 8. With teamwork and camaraderie, Byergo worked together in the game against Lafayette High School. “[Byergo’s] is really positive with a good spirit,” Lanferseick said. “I set her [the ball] and she hits it [or] gets the kill.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_9349-1-e1761159125735-1200x791.jpg)

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

![Freezing in their position, the Addams Family cast hits the “rigor mortis” pose after cast member and senior Jack Mullen, in character as Gomez Addams, calls out the stiff death move. For the past four months, the combined company of cast members, orchestra pit, crew and directors all worked to create the familial chemistry of the show. “I’m excited for [the audience] to see the numbers, the music, the scenes, but I also just love all the technical aspects of it. The whole spectacle, the costumes, makeup and the people that put in the work backstage in order to make the show successful on stage. I’m excited for people to see and appreciate that,” Mullen said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/DSC0116-1200x800.jpg)