1,700 students, 75 countries, 6 days and $4 million on the line as prizes for the future of science. This is the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair.

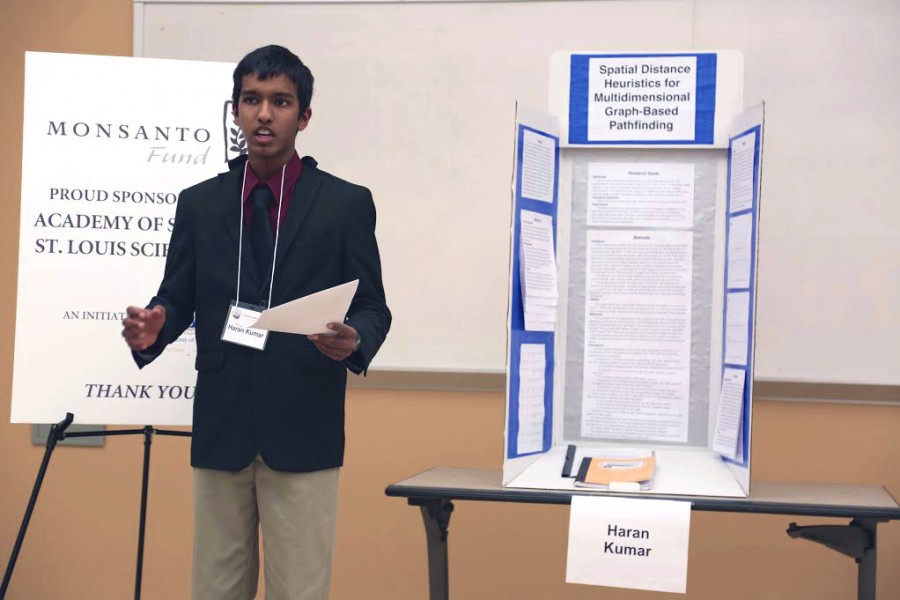

On Feb. 27, sophomore Haran Kumar won a second place award at the St. Louis’ Academy of Science fair’s Honor division competition in a field of almost 50 competitors, receiving a $1,000 scholarship along with a chance to go to Intel’s international science fair. His project was a study and model of something most of us cannot begin to comprehend: multidimensional pathfinding- like Google maps, but bigger. An extension to limited research in the field, Kumar’s program could have such applications as asteroid belt navigation in space and guidance programs to enhance mobility for the blind.

That sure sounds like science to me–but it looks like Parkway doesn’t think so.

Boasting a well-established science program, more than 70 percent of all students in the district score Proficient or Advanced on the Science portion of the MAP tests. West High alone offers almost 30 different science courses to students, and nearly every common assessment secondary students take has questions about the nature of a scientific experiment. Accordingly, Parkway’s Science Fair also follows a rigid experimental design rubric requiring exactly one Independent Variable, one Dependent Variable and a detailed procedure.

With all of their STEM initiatives, you might think Parkway would be eager to recognize the high level of scientific and engineering prowess found in Kumar’s computer program, but when the young scientist went to the District fair at Southwest Middle fair on Feb. 26, he walked away with a Green ribbon. While almost half of students went off with Purple ribbons qualifying them for the Greater St. Louis fair at Queeny Park, Kumar was effectively sent home for the year, all because he was a creator rather than an experimenter.

Here lies the core problem with Parkway’s vision of students in science: they only see one path to success. To any layperson, Kumar’s computer program and accompanying research would seem a detailed scientific endeavor. In the next month, Kumar is going so far as to rewrite and improve his program, as flexibility and development are major elements of science. At the fair, however, Kumar’s project was judged negatively, for not having an independent variable, a measurable dependent variable, a simple line graph. A hundred boring, simple lima bean and water presentations with pretty paper could have taken home purple ribbons with this system.

Evidently, Parkway doesn’t see it’s students like scientists in their science fair. The narrow judging rubric treats science like a one-size-fits-all equation, when in reality, the most successful and ground breaking projects often develop not as rigid experiments, but as ideas, inventions and cumulative research. The most absurd part- students at the fair are even allowed to present engineering projects at the fair–but not when they reach high school, the time when students just start to understand advanced scientific concepts.

Another barrier Kumar faced—or should I say, didn’t face—at the fair, was that he, like all students, was not required or allowed to present his projects to judges himself. After listening to Kumar explain the complexities of his program in person, (I had to ask a lot of questions) I know for a fact that I would not have been able to sufficiently understand the program with a paper board- and I judged at the fair. This issue demonstrates Parkway’s main concern with efficiency over quality. Pulling judges from the student body and families primarily, Parkway neglects to take advantage of the expertise of science professionals who can actually understand complex topics and encourage students to apply their research.

The fact is, today’s students are smarter and more passionate about science than ever before. If Parkway wants to encourage future scientists, the focus needs to be shifted away from the grade and towards the realm of understanding and innovation. Parkway should offer an engineering division to high school students, just as Intel does, to prevent such an embarrassment to the system as Kumar’s project created. Last year, the grand prize winner of the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair created a way to prevent disease transmission in airplane cabins—professional level research—and he did not win the fair with a dinky data table.

![Sitting courtside before a junior varsity girls’ tennis match, senior Tanisi Saha rushes to finish her homework. Saha has found herself doing academic work during her athletic activities since her freshman year. “Being in sports has taught me how to stay organized and on top of my schoolwork. [With] a busy practice and game schedule, I’ve learned to manage my homework and study time better,” Saha said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC_0022-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Maryem Hidic signs up for an academic lab through Infinite Campus, a grading and scheduling software. Some students enjoyed selecting their responsive schedule in a method that was used school-wide last year. “I think it's more inconvenient now, because I can't change [my classes] the day of, if I have a big test coming and I forget about it, I can't change [my class],” sophomore Alisha Singh said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0012-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)

![Junior Fiona Dye lifts weights in Strength and Conditioning. Now that the Trump administration has instituted policies such as AI deregulation, tariffs and university funding freezes, women may have to work twice as hard to get half as far. "[Trump] wants America to be more divided; he wants to inspire hatred in people,” feminist club member and junior Clara Lazarini said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Flag.png)

![As the Trump administration cracks down on immigration, it scapegoats many immigrants for the United States’ plights, precipitating a possible genocide. Sophomore Annabella Whiteley moved from the United Kingdom when she was eight. “It’s pretty scary because I’m on a visa. When my visa expires next year, I’m not sure what’s going to happen, especially with [immigration] policies up in the air, so it is a concern for my family,” Whiteley said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0077-7copy.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Some of the most deadly instances of gun violence have occurred in schools, communities and other ‘safe spaces’ for students. These uncontrolled settings give way to the need for gun regulation, including background and mental health checks. “Gun control comes about with more laws, but there are a lot of guns out there that people could obtain illegally. What is a solution that would get the illegal guns off the street? We have yet to find [one],” social studies teacher Nancy Sachtlaben said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_5122-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Shree Sikkal Kumar serves the ball across the court in a match against Lindbergh. Sikkal Kumar has been a varsity member of the varsity girls’ tennis team for two years, helping her earn the number two rank in Class 2 District 2.“When matches are close, it’s easy to get nervous, but I [ground] myself by[staying] confident and ready to play,” Sikkal Kumar said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC2801-1200x798.jpg)

![Dressed up as the varsity girls’ tennis coach Katelyn Arenos, senior Kate Johnson and junior Mireya David hand out candy at West High’s annual trunk or treat event. This year, the trunk or treat was moved inside as a result of adverse weather. “As a senior, I care less about Halloween now. Teachers will bring their kids and families [to West’s Trunk or Treat], but there were fewer [this year] because they just thought it was canceled [due to the] rain. [With] Halloween, I think you care less the older you get,” Johnson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC00892-1-1200x800.jpg)

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)