Macklemore may have to update the lyrics to his 2012 hit single “Thrift Shop” soon because as we head into a new era of thrift stores, the line “But it was 99 cents (bag it)” now reads like a cruel joke to any long-term patron of thrift stores.

Economic inflation has been wreaking havoc on industries nationwide, with prices increasing by 6.0% in February 2023. At first glance, thrift stores would also be increasing to adapt to the changing market. However, this inflation runs deeper than just currency.

“Thrift stores have more than clothes; they have houseware [items]. Kitchenware, dishes, microwaves, kid’s toys, bedding, anything you can think of. That’s just going to make [finding things at thrift stores] increasingly difficult for [lower-income families],” junior Kristin Skordos, a former employee of Savers, said.

Goodwill was ranked the seventh largest charity in 2022 and is one of the biggest chain thrift stores, boasting over 3,000 locations in the United States and Canada alone. Though claiming their only purpose is to “transform lives through the power of work,” Goodwill has a history of choosing profit over people, such as when it came under fire in 2012 for paying disabled employees under the minimum wage.

Goodwill has recently joined other thrift stores to raise prices through a “tiering system.” They have three tiers of products: base price, tier one and tier two. Prices of products increase with every tier. This tiering system means that depending on the quality or brand of a piece, the price could increase by up to 250%.

“There are three main tiers. The base one is the [least expensive] tier, the middle tier you’re going to get a more worn out designer, then the third tier is the most expensive, that’s straight out-of-the-box type stuff. I can notice a big difference between tier one and tier three,” junior Will Anderson, a former Goodwill worker, said.

Goodwill has also launched an online store with the intention of upcharging more valuable items. The website places a minimum base price on an item, and then consumers bid on the item of interest. However, a first look at the site procured listings of Shein and Forever21, with the base price for some items being only a few dollars lower than the retail price. This encourages consumers to bid higher than the base price of the item, which leads to them paying more for it than it would cost from Shein or Forever21. While the model of a website that can charge more for more valuable items makes sense, charging $15 and higher for out-of-season, Shein is just greedy.

Price increases from national chain nonprofits to local charity shops are hitting the second-hand industry. However, prices aren’t going up for no reason; they fluctuate due to consumer behaviors.

The 2010s and 20s have seen the largest shift in public perception of thrift stores. Beginning in the early 20th century as charity shops often run by religious organizations or figures, they quickly obtained a reputation as purely for the “poor and needy.” These classist implications became more than implications in the mid to late 20th Century as thrift stores carried a stigma among many middle-class families of being “dirty,” and children from lower-income families were commonly ostracized for having to buy from thrift stores.

Simply put, teenagers from middle-class to upper-class families wouldn’t have been caught dead in the Salvation Army. Those who may have chosen to venture into one were often mocked by their peers.

“My parents were both extremely, extremely poor when they grew up. My dad came from a third-world country, and my mom was from a lower-income family,” junior Inaya Chishti said. “My mom [went] to high school, and everybody else was wearing nice, new clothes and [she wore] Goodwill clothes, and all of her clothes were passed down. As an immigrant, my dad couldn’t afford the nice clothing the white doctors had. Though they aren’t living those lifestyles [anymore], the lifestyles that they used to live were traumatizing [for them].”

However, this all changed in the mid-2010s with the rise of influencer and vlogger culture. Influencers like Emma Chamberlain presented thrift stores as an affordable source of less common yet cute clothes for the average teenager who does not have the resources to frequent vintage boutiques. This trend has led to purchasing at thrift stores being a more acceptable practice and a hobby. This has even led to the invention of the term “thrifting” to describe the act of recreational shopping at thrift stores.

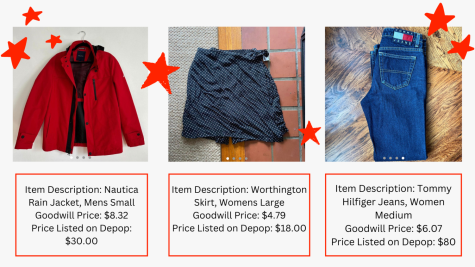

Nowadays, it’s not uncommon to see videos on TikTok of influencers stumbling upon vintage Harley Davidson tees or rare Miss Me jeans with retail prices in the hundreds or upcyclers who take “ugly” clothes and turn them into unique and flattering pieces. And more likely than not, most teenagers have probably seen “resellers” that hunt for pieces to upcharge and resell on the online store Depop.

“I think [resellers] are killing [thrift stores]. It’s like big chain restaurants like McDonald’s, and then [thrift stores are] like a little Ma-and-Pa burger place. But people don’t [pay] much attention to it. Depop’s killing thrifting, and it’s ruining their prices and raising them,” Skordos said.

This internet subgenre of “thrift hauls” or “thrift with me” videos generally consists of middle-class to upper-middle-class influencers visiting thrift stores and buying gross sums of clothes. These clothing items are often subversive garments, such as clothes intended for plus-sized people, children’s clothes or leather jackets, all items typically less common in thrift stores and all the more necessary for lower-income shoppers.

As shopping at thrift stores becomes a more normalized and appreciated hobby, those who need their services most are marginalized and hurt by this new appreciation. Contrary to popular belief, this contemporary embrace of thrift stores has done very little to help lower-income citizens. Though the normalization of thrift stores has helped to support small second-hand stores as well as mitigate stigma towards impoverished people for their reliance on thrift stores, because of price increases, this has ultimately made thrift stores less accessible to people who require them.

Another big topic in the popularization of thrift stores is sustainability and overconsumption. Since lower-income people are undeniably the most affected by climate change, removing the class factor from conversations about climate change and fast fashion is impossible. Thrift stores are often filled with discarded fast fashion clothes from companies like H&M or FashionNova, thrown out from the superfluous hauls by the upper middle class into thrift stores.

By using thrift stores as make-shift trash cans to dispose of wasteful fast fashion hauls and the environmental guilt that comes with these purchases, the upper classes use these resources to absolve themselves of their shopping guilt. There is a widely held idea that donating unwanted clothes erases the original irresponsibility of the unnecessary purchase.

However, the truth is much more unfortunate. Many donated clothes do not reach the standards of thrift stores and do not make it out onto floors, so a whopping 84% of donated clothes end up in landfills. Though donating these clothes is ultimately better than throwing them away, thrift stores are not the easy fix to unsustainable buying habits that people think.

While the complications with thrift store shopping go beyond price increases and fast fashion brands, they are also much more simple than that. It comes down to the concept of quantity.

It’s easy to be mindless while thrifting; even with price increases, the comparatively low prices allow many consumers to impulsively buy without thinking about potential consequences. Though each incremental price increase may exponentially impact lower-income buyers, for the growing base of middle-class patrons, these prices mean very little.

For the middle class, if they buy a $4 blouse they never wear, who cares that they wasted a measly $4? If a reseller buys masses of shirts and jeans and bags and sweaters, the potential profit they could make off of reselling on Depop massively outweighs the initial cost they would’ve paid for in-store.

With most stores, the vast quantity of uniform clothes removes any responsibility on the consumer to not overbuy — at least at the expense of other buyers. But when someone wastefully and thoughtlessly buys clothes from a thrift store, they take clothes away from someone else who could use them.

“[Thrifting] is just something that sometimes [people] have to do. Maybe it’s becoming more mainstream or ‘normalized,’ but it’s becoming even more classist and making people feel like, ‘Oh yeah, this is cool. I need it more than you do,’” Chishti said.

As a result of the financial struggles many teenagers are increasingly facing, this issue affects high schoolers at a disproportionate rate. Despite being at a point where fashion and fitting in become incredibly important, teenagers rarely have the money to fund this spending.

“A lot of high schoolers are working minimum wage jobs, and a lot of their parents do not fund [their] shopping addiction,” Chisti said.

Considering all these things, it is still important to understand that arguing against the mainstream utilization of thrift stores altogether is faulty and dangerous. Using an “all-or-nothing” attitude toward anything is wrong, but especially towards something as fragile as the economies of second-hand stores, which, unlike most other retail stores, do not exclusively cater to one type of buyer, but instead have a consumer base that messily weaves together people from all demographics.

Instead, we should advocate for thoughtful appreciation of our second-hand stores. Though shoppers may be able to relax more about the stresses of sustainable sources and prices when they enter their local Goodwill or Savers, it is important to remember that mindful consumption should follow us no matter where we might be shopping.

Buying things that won’t come to use is a waste, regardless of where they come from, and reselling harms the economy of thrift stores. Second-hand stores have a purpose: to provide communities with low-cost textiles and wares to bridge the gap between the classes of America.

![For the first time in fashion history, thrift stores have become as essential to the middle class as they are to the impoverished communities they were designed to serve. The potential effects on lower-class communities are worrying. As thrift stores increase prices to meet resellers’ upcharges, the longtime, poorer buyers will be left feeling the effects: thrift store merchandise will not be as accessible or affordable to them. “It’s just going to separate the lower class from [the resources] they [need], and it will separate [the] middle and higher classes. It will make things a lot more difficult,” junior Kristen Skordos said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/OVERCOMSUMPTION-10.png)

![Sophomore Maryem Hidic signs up for an academic lab through Infinite Campus, a grading and scheduling software. Some students enjoyed selecting their responsive schedule in a method that was used school-wide last year. “I think it's more inconvenient now, because I can't change [my classes] the day of, if I have a big test coming and I forget about it, I can't change [my class],” sophomore Alisha Singh said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0012-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)

![Junior Fiona Dye lifts weights in Strength and Conditioning. Now that the Trump administration has instituted policies such as AI deregulation, tariffs and university funding freezes, women may have to work twice as hard to get half as far. "[Trump] wants America to be more divided; he wants to inspire hatred in people,” feminist club member and junior Clara Lazarini said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Flag.png)

![As the Trump administration cracks down on immigration, it scapegoats many immigrants for the United States’ plights, precipitating a possible genocide. Sophomore Annabella Whiteley moved from the United Kingdom when she was eight. “It’s pretty scary because I’m on a visa. When my visa expires next year, I’m not sure what’s going to happen, especially with [immigration] policies up in the air, so it is a concern for my family,” Whiteley said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0077-7copy.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Some of the most deadly instances of gun violence have occurred in schools, communities and other ‘safe spaces’ for students. These uncontrolled settings give way to the need for gun regulation, including background and mental health checks. “Gun control comes about with more laws, but there are a lot of guns out there that people could obtain illegally. What is a solution that would get the illegal guns off the street? We have yet to find [one],” social studies teacher Nancy Sachtlaben said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_5122-1200x800.jpg)

![After a thrilling point, senior Katie Byergo and junior Elle Lanferseick high-five each other on Oct. 8. With teamwork and camaraderie, Byergo worked together in the game against Lafayette High School. “[Byergo’s] is really positive with a good spirit,” Lanferseick said. “I set her [the ball] and she hits it [or] gets the kill.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_9349-1-e1761159125735-1200x791.jpg)

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

Inaya • Apr 11, 2023 at 12:55 pm

Thank you for including my parents stories in your article! I think this is something that should be talked about more!

Audrey Ghosh • Apr 6, 2023 at 11:46 am

I am so impressed by the thoroughness of this story! Great work, Lauren.

Serena Liu • Apr 6, 2023 at 9:23 am

Super interesting story Lauren!