Disclaimer: Some links in this article contain explicit lyrics or profanity.¬Ý

The age of peak modern hip-hop controversy has begun.¬Ý

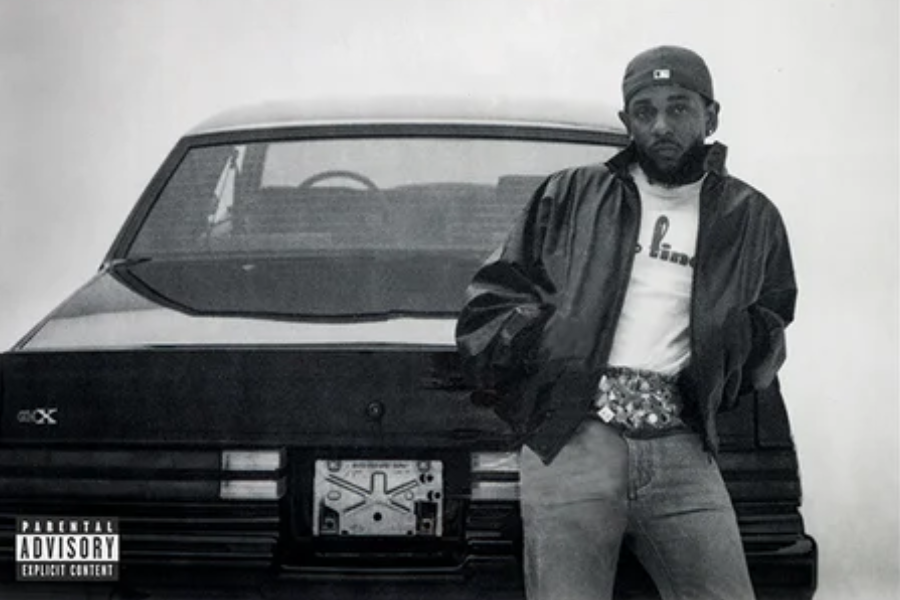

Arguably, the most thrilling topic in music news amidst the new year has been the infamous rap battle between rappers Drake and Kendrick Lamar. Through a series of new tracks, some dropped within 24 hours of each other, the two hip-hop sensations have drawn all the eyes of the internet towards dramatic production, clever lyrics and backhanded comments.¬Ý

But as the internet obsesses over the intricacies of a reborn hip-hop battle straight out of the ‘90s, our world continues to face a battle much greater than our sources of entertainment. As we analyze the lyrics and flow of new diss drops, the other side of the planet suffers at the expense of catastrophic weaponization. The death toll in the Gaza Strip is in the tens of thousands and counting, yet we continue to discuss a musical endeavor that is simply too frivolous in relevance to what we know others presently encounter.

To say that we should be able to enjoy the music culture of our side of the world in peace, while the other side of the world encounters one of the largest humanitarian crises of our decade, is a regurgitated, ignorant statement. Yes, music is a part of our culture and a source of entertainment ‚Äì but music is also a mode of expression, and in some cases, a method of calling for change. The music that we listen to strikes us in ways that simple words cannot. The music that we listen to connects us under shared interest. The music that we listen to reflects who we are, both as individuals and as collective communities.¬Ý

So why are we so quick to send backlash at music that speaks directly for a group’s echoing political protests?

The first songs began, not as chart-topping, gossip-stirring hits, but as storytelling mechanisms used to pass on memorable lessons. Music cannot — and should not — stop doing that for people. The ridicule that songs made solely for political expression face leaves us consistently forgetting the basis of music’s intent. With the growth of aversion to political music, we’ve been limited to tracks like singer Taylor Swift’s “The Man” — recognizable pieces that address conceptual politics in a palatable manner, but lack direct calls to specific organizations or people perpetuating them — in contrast to the Billie Holidays of our history.

It‚Äôs okay to listen to music that simply makes you happy; it‚Äôs not okay for that music to be the sole genre you are provided to digest. While listeners are limited to apolitical pop tracks, musicians are abusing their platforms and ignoring their abilities to empower marginalized voices. We can never forget that, silly as it seems, it is a privilege to be analyzing new rap battle drops in the comfort of our homes. Because they have a platform that others don‚Äôt, artists have an obligation to create music that supports those who cannot speak for themselves. They have the voice that so many others have been stripped of ‚Äî it‚Äôs essential to use it.¬Ý

This is an argument to bring forth, not as much to the listeners, but to the ones creating the music that the public listens to. Music is part of so many of our daily lives, so the impact of an artist who broadcasts a message for the good of a group of people can be seismic. And who would have guessed: our strongest example of this necessity would be none other than a 2024 protest single from Mr. “Thrift Shop” himself, rapper Benjamin “Macklemore” Haggerty.

A message for the people

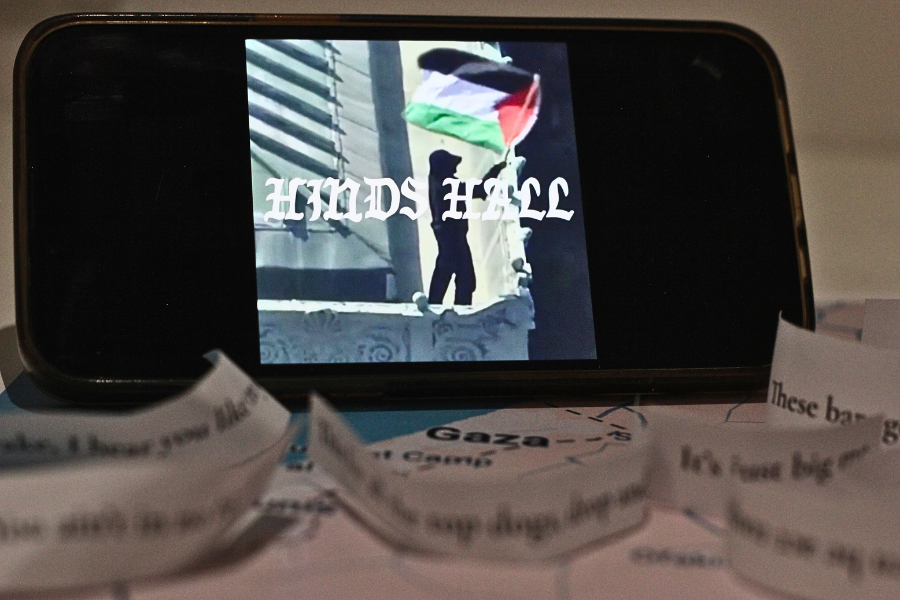

On May 6, Macklemore released the standalone single ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall,‚Äù a distinct, politically charged rap track about the current Israel-Palestine conflict, which quickly stirred much political controversy. The title ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù pays homage to the actions of Columbia University student protesters, who assumed control over a university building on April 30 and informally renamed it Hind‚Äôs Hall after Hind Rabaj, a Palestinian girl killed by Israeli troops during an attack in January. Consequently, the track echoes the goals of pro-Palestinian student protesters through lyrics that target several organizations complicit in Israel‚Äôs invasion.¬Ý

‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù opens with a striking sample of ‚ÄúAna La Habibi” by Lebanese singer Fairuz, a traditional Arabic minor melody that quickly establishes its place beneath Macklemore‚Äôs otherwise isolated vocals in his first verse. The opening lyrics ‚Äúthe people, they won‚Äôt leave‚Äù summarize the underlying theme of Macklemore‚Äôs new track: citizens won‚Äôt hesitate to continue fighting for justice in the face of adversity.¬Ý

Rooted in its defense for student protesters, the track portrays Macklemore’s approval of the actions of Columbia University’s – and various other colleges’ — student populations protesting war in the Gaza Strip. In the third line, the rapper asserts “the problem isn’t the protests, it’s what they’re protesting,” implying that the freedom of speech outlined in our First Amendment is often limited by public institutions when that speech interferes with their values. In a standout bar later in the track, Macklemore continues to call out university administrators who have threatened the student protesters: “If students in tents posted on the lawn occupying the quad is really against the law/And a reason to call in the police and their squad/Where does genocide land in your definition, huh?”

With a blare of horns and a kick drum beat drop, Macklemore‚Äôs second verse serves as an extensive tirade against U.S. government officials, complicit organizations and their general lack of response to foreign crises. The lyrics ‚Äúyou can pay off Meta, you can‚Äôt pay off me‚Äù and ‚Äúyou can ban TikTok, take us out of the algorithm‚Äù refer to recent government restrictions and censorship on controversial topics similar, but not constricted to, the Israel-Palestine conflict. The issue has left many social media users complaining of a lack of pro-Palestinian representation in the media due to the effects of shadowbanning or even outright censorship.¬Ý

A symphony of horns midway through the verse embellishes this track into a musical blend of classic hip-hop rhythm with cultural undertones that leave an impressively haunting tone ‚Äî the sound of a warning to the public. The composition is heightened with the incorporation of various minor string melodies throughout the song, which often cut to a stripped beat at Macklemore‚Äôs most direct lines. ‚ÄúI want a ceasefire, f*ck a response from Drake” being a clear example, Macklemore references the rap battle overtaking the internet as an attempt to avert social attention from such trivial matters towards acts of political uprising and social justice. These movements leave a much more perpetual impact on how our country functions; Macklemore doesn‚Äôt aim to minimize the validity of rap battles, but instead distinguish their relevance in the context of current world affairs.¬Ý

“Hind’s Hall” concludes with the devastating, departing words that “if the West was pretending that you didn’t exist, you’d want the world to stand up, and the students finally did.” And while the student protesters Macklemore refers to have been true representation of this particular freedom of democracy, the release of his track solidifies Macklemore as part of that world that is standing up. It’s the history of what he concludes in “Hind’s Hall” that signifies its intent: a digestible method of political expression that will secure “Hind’s Hall” as a musical legacy for years to come.

Music as the vessel of change¬Ý

‚ÄúNever be defeated when freedom‚Äôs on the horizon/Yet the music industry‚Äôs quiet, complicit in their platform of silence.‚Äù¬Ý

This last statement of “Hind’s Hall”’s third verse contends what we’re truly meant to take away from Macklemore’s latest release. It is no secret that the music industry has a history of stirring up controversy with extreme political statements. The concept has been prevalent for a long time; jazz singer Billie Holiday took heavy blowback in the 1930s after the release of her controversial song “Strange Fruit.” The topic of concern — racism in America after emancipation — was depicted in the song with graphic verbal descriptions of lynchings of Black Americans in southern states. The emotional, haunting melody quickly garnered public aversion after its release, resulting in most radio stations banning the song and nightclubs shutting down Holiday’s performances.

Holiday wasn‚Äôt the first of her time, and she most definitely was not the last. But in the light of music‚Äôs effect on the economy, and particularly how much it can provide to corporations supporting certain musical artists, it has grown increasingly difficult to continue with political expression in music. We can see it in Holiday‚Äôs catastrophic response after releasing ‚ÄúStrange Fruit‚Äù when the U.S. government set up an operation to arrest Holiday for drug possession: alignment with a controversial political viewpoint can lead to detrimental effects for an artist.¬Ý

The specification that comes from announcing a political viewpoint can also ostracize a musician from listeners, especially when the media works to downplay or even demonize such music. Add in the influence of commercialization and the rise of statistical awareness with the prevalence of streaming services, and speaking up about politics can become a matter of choosing between a secure dream job and unemployment.¬Ý

In fact, ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù reflects that ostracization, coming with respective challenges and community discourse. Upon its initial release, the track was only available on YouTube due to streaming service limitations; however, even on YouTube‚Äôs platform, the song was facing its own subtle version of limitation. Marked for ‚Äògraphic and violent content‚Äô and restricted by an age limit, the song was accused by many of being shadowbanned or even censored by YouTube ‚Äî wrongfully so, when compared to various freely available YouTube videos that echoed pro-Israeli sentiments. ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù is now available on both streaming platforms and YouTube, but the audience lost from the momentary restrictive censorship has likely affected the scope of the track‚Äôs outreach.¬Ý

Though differing from Holiday in severity, the restriction placed on Macklemore‚Äôs release retraces the stages of old history, stages that need to be broken down to make room for modern reform. In the face of backlash, some historical songs have found ways to express political opinion on global matters in the past, examples of a necessary battle to endure in the attempt to emphasize public voice. But this doesn‚Äôt mean that there isn‚Äôt much more change to be done; the treatment of ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù is simply another verification of that.¬Ý

Macklemore‚Äôs past in vocalizing his support for racial and social justice grants him an experience of activism unlike most modern music artists. His greatest participation in political activism reaches as far as marching in protests himself; most notably, Macklemore joined protesters in Seattle who were condemning the shooting of Michael Brown as a result of police brutality. The rapper has also continuously posted and vocalized his criticism of former president Donald Trump. Social media posts and protest participation aren‚Äôt Macklemore‚Äôs only medium, however: he also has a history of creating songs made solely to spread a political message.¬Ý

In 2005, Macklemore released the track “White Privilege,” which was met with varying levels of praise and condemnation. Its follow-up, “White Privilege II,” produced by Ryan Lewis, analyzes the perspectives of the responses to the first track in a raw, vulnerable manner. Macklemore references sentiments others have expressed about his role in the Black Lives Matter movement, interrupted by his own inner dialogue attempting to consider how he can be a better social justice activist while acknowledging his inherent privilege as a white man. Years later, in 2016, the rapper collaborated with Lewis again in “Same Love,” an unapologetic, pro-LGBTQ+ rights anthem that advocated for same-sex marriage equality.

Macklemore‚Äôs history of activism is proof that politics and music ‚Äî specifically hip-hop ‚Äî are inherently aligned. His mistakes and successes reveal that putting politics into a widely public art form like music may not always work, but simply attempting to spread a message that starts conversations can end up making a difference.¬Ý

Proclamation enacts discussion. Whether you agree with the rapper‚Äôs consensus in ‚ÄúHind‚Äôs Hall‚Äù or not, Macklemore should be applauded for one thing at the very least ‚Äî standing up to generalizations that restrict music and activism from creating impact. The track has, and will continue to, receive extreme responses from the public ‚Äî praise, anger, or even outright censorship ‚Äî but that’s just an unfortunate result of artists proclaiming their political views in music. As the clamor grows louder, protest music develops into more and more of an anomaly. Amidst apolitical pop hits or internet-capturing feuds, to be a Macklemore is to truthfully establish yourself as someone unafraid to position yourself between worlds. Politics and music can unite, and truly should in a genre like hip-hop, rooted in self-expression through lyricism. So rather than press play on the next diss track, shuffle out of your comfort zone and through some political playlists. Don‚Äôt be afraid to embrace the music of a movement.¬Ý ¬Ý ¬Ý ¬Ý

![There are more than 20 open cardio machines at Crunch Fitness. I enjoyed the spacious environment at Crunch, a sentiment that was shared by sophomore Sanjana Daggubati. “[Going to] Crunch Fitness was the right decision because [it] feels more professional. Crunch’s workers are laid back, but not to the point where they don't care,” Daggubati said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5242-1-1200x900.jpg)

![Various empty Kit Kat wrappers crowd the desk, surrounded by scoring sheets. While production of Kit Kat flavors in the U.S. is limited, Nestlé, the owner of Kit Kat, manufactures hundreds of unique flavors in Japan, including the flavors ocean salt and passion fruit. “I thought there [were] some interesting flavors, and a lot of them were really unexpected,” senior Elle Levesque said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/image-2.png)

![Pantone’s selection of the 2025 Color of the Year is revealed: Mocha Mousse. Ceramics teacher Ashley Drissell enjoys this year’s selection. “Maybe it’s the name but [Mocha Mousse] reminds me of chocolate and coffee. It makes me hungry. It’s very rich and decadent,” Drissell said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/DSC_0015-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Shree Sikkal Kumar serves the ball across the court in a match against Lindbergh. Sikkal Kumar has been a varsity member of the varsity girls’ tennis team for two years, helping her earn the number two rank in Class 2 District 2.“When matches are close, it’s easy to get nervous, but I [ground] myself by[staying] confident and ready to play,” Sikkal Kumar said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC2801-1200x798.jpg)

![Dressed up as the varsity girls’ tennis coach Katelyn Arenos, senior Kate Johnson and junior Mireya David hand out candy at West High’s annual trunk or treat event. This year, the trunk or treat was moved inside as a result of adverse weather. “As a senior, I care less about Halloween now. Teachers will bring their kids and families [to West’s Trunk or Treat], but there were fewer [this year] because they just thought it was canceled [due to the] rain. [With] Halloween, I think you care less the older you get,” Johnson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC00892-1-1200x800.jpg)

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

Will Gonsior • May 29, 2024 at 3:21 pm

A well-considered silence is always okay, but it’s also good to take a stand for what you believe in. Nobody knows how many people are dead in Gaza, and the only ones who know how the Israeli targeting priority system works are the Israelis themselves. We don’t know if there’s a genocide. Considering what happened when we last saw mass student protests (we elected the worst president of the modern era in Richard Nixon), I doubt the efficacy of protesting now. However, this article reminded me that, whatever else goes on, it’s important to make your voice heard. And, frankly, I love it. It’s good. Thank you, Risa.