Most people in America would think a pink toothbrush printed with beaming, blushing Disney princesses on the side is nothing out of the ordinary. Most people wouldn’t think twice about seeing a new electric car. Most Americans wouldn’t even blink at the vast, looming stores filled with fresh food, medicinal supplies, and more toys than any child would know what to do with. But most people in America haven’t immigrated from one of the poorest countries in North America. Freshman Sabrina Urdaneta, along with her parents and her aunt and uncle, immigrated to the United States from Cuba at seven.

Urdaneta has a complicated relationship with her home country.

“I definitely miss Cuba,” Urdaneta said. “I don’t wish that I was back there, and I like it more here because our life is a lot easier than [it was] in Cuba, but I miss it.”

Urdaneta was born near Santiago de Cuba, a city near the southernmost coast of the country of Cuba. She has a lot of great memories from her childhood, especially with her family and friends, who she cherishes a lot.

“Every Friday, my aunt would pick me up and take us to the beach house, and we’d go to the beach for the weekend. We would sleep in the sand at the beach,” Urdaneta said. “I had so many friends in the beach house. My best friend lived in the neighborhood, too. I do miss it very much.”

Although the circumstances were challenging, Urdaneta believes her parents provided her with the best childhood as a child. Seeing her and 16 other children playing in the backyard, loudly shrieking and giggling, wasn’t uncommon.

“I had so many friends because everyone is friends with everyone in Cuba. Every single one of my neighbors was all over at my house. My house was the house of choice since it was the only one that had a garden in the entire neighborhood,” Urdaneta said. “All the kids were in my backyard, from toddlers to 15-year-olds, every single day. I loved it.”

Both Urdaneta and her parents were deeply involved in the community around her, as Cuban culture typically dictates. Cuban culture is deeply rooted in familial and community love.

“My parents always hosted [parties]. There was a huge mango tree outside of our house, so we’d climb the trees and get the mangoes,” Urdaneta said. “People would be inside playing board games, music was everywhere, and three people were cooking in the kitchen that we didn’t even know. It was always chaotic, but it was so much fun.”

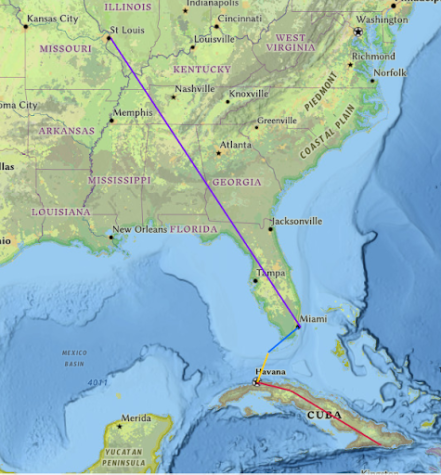

Even though Urdaneta has positive memories of Cuba, it didn’t negate the negatives of living in Cuba for her parents, who badly wanted to immigrate to the United States. If a resident citizen has a Spanish passport in Spain, then the next two generations also have a Spanish passport. In addition, Spanish citizens can get into the United States with visas on arrival. Urdaneta’s grandfather was one such Spanish citizen. He ended up immigrating to Cuba, which meant that Urdaneta and her family—the next two generations—received Spanish passports and the opportunity to immigrate. Since they were teenagers, Urdaneta’s parents had been trying to get into the United States, but saving up money to get anywhere was a struggle. Finally, the family had the chance to leave Cuba in 2013.

“Nobody wants to live in Cuba,” Urdaneta said. “My mom didn’t want me to spend my entire life struggling, and she didn’t want my [future] children to spend their entire lives struggling either. She wanted me to have better opportunities and a better life so that I wouldn’t have to go through everything she had to go through.”

Simple items like body wash, soap, and toothpaste commonly found in drugstores around America are a struggle to find in Cuba. So Urdaneta was surprised when she visited a dollar store and found an item that most people in America would deem unordinary.

“[We were in] Dollar Tree, but the store was the most beautiful thing to me, ever. I saw a pink toothbrush with princesses on it. It had Princess Rapunzel and Aurora. It was an electric toothbrush. I didn’t even beg for it, I looked at the toothbrush, and my jaw dropped,” Urdaneta said. “My uncle got it for me, and it was the best day of my life because that pink toothbrush was everything to me. And it was electric; they don’t exist in Cuba! Toothbrushes barely exist in Cuba, so it was the coolest thing I had ever seen, and I loved it so much.”

Although immigrating to America was the goal, once arriving, Urdaneta says life still was not very easy. Urdaneta’s family that immigrated – including her mother, father, aunt and uncle – did not speak English, making it difficult to find a job. In addition, her family didn’t have a car which forced them to walk everywhere, which was especially challenging when grocery shopping or going to school.

“When we first got here, my family didn’t have a lot of money. So we lived in a really tiny apartment with five people, with three people sleeping in one bed and two people sleeping in the living room,” Urdaneta said.

When Urdaneta first came to the United States, she began school right away at Nahed Chapman. However, because she didn’t speak the English language, Urdaneta was held back for a year and had to attend summer school.

“At summer school, all of the kids were American. I couldn’t speak English, and I couldn’t find my way around the school, so I just sat down in a corner and cried,” Urdaneta said. “A teacher came up and tried to talk to me, but she couldn’t understand what I was saying, and I couldn’t understand what she was saying, so she just took my hand and took me to the front office, where they finally found someone who could speak Spanish. It was awful. I hated it.”

After she learned the language quickly and her parents received their work permits, Urdaneta felt that her life was finally easier than it had been in Cuba. Urnadeta and her family moved into a house and got a car.

“Everything changed drastically,” Urdaneta said.

Coming to America was a culture shock in the language, the number of new experiences Urdaneta had, and societal expectations. According to Urdaneta, Cuban culture tends to be extroverted while American culture is a bit stifled in comparison.

“At least people who live in poverty in Cuba, they’re still going to have a roof over their heads most of the time. You’re not going to see many people out on the streets by themselves in Cuba, [generally because] Cubans are more friendly. So if there’s somebody on the streets in Cuba, you can bet that somebody’s going to walk by them and take them home,” Urdaneta said. “But here in the United States, people are living in boxes next to McDonald’s and gas stations, and it’s really sad to see that.”

There are many striking differences between the governments of the United States and Cuba. Cuba is infamous for being ruled by its only party, the Communist Party of Cuba. The party strikes down on independent media and does not provide sufficient laws for government transparency, meaning that citizens cannot question the government’s decisions, nor is there a way to hold the Cuban government accountable.

“Freedom of speech is something that just doesn’t exist in Cuba. If you have something bad to say about the government, you’re going straight to jail,” Urdaneta said. “People constantly live in fear in Cuba about saying anything, just in case if anyone’s listening because there are a lot of government spies.”

(Photo courtesy of Sabrina Urdaneta)

Now that she’s grown from a child to an informed teenager, Urdaneta finds that the experience shapes her and her family’s strong political opinions in Cuba.

“Even though my life is no longer in that danger, my family members are still over there, and Cuba has gotten so much worse since I [immigrated],” Urdaneta said. “So many people that I know and love that are going to spend the rest of their lives in Cuba, so many people are going to die [from that]. My sister’s 18-years old, 4 feet-11-inches and is as skinny as a noodle because she’s dying of dehydration and malnutrition, and that’s most people in Cuba.”

One of the problems that Urdaneta acknowledges is the health care system. Although Covid-19 numbers in Cuba are only moderately severe, the health system in Cuba still lacks in other ways, as medicinal drugs and procedures are very costly or they don’t exist. Urdaneta believes that this is a problem that needs to be fixed immediately for the well-being of Cuba’s citizens.

“I remember when I was a little kid, I had asthma, and just to get a [nebulizer] when I had asthma attacks was a huge struggle in Cuba,” Urdaneta said. “Mothers have to give birth without anything. There are no epidurals and nothing to kill the pain. There’s no c-sections allowed. It’s ridiculous.”

Although immigrating to America was a huge difference for Urdaneta, her family keeps her culture and cultural traditions alive in their home. For example, Urdaneta’s family does not speak English inside of their home, and a typical dinner is rice, meat and salad, which is what a typical meal for them in Cuba would look like.

“Sometimes I get tired of it, like, I want Chick-fil-a, but my family has kept our culture the same,” Urdaneta said. “We eat the same food, and we listen to the same [kind of] music in my house. So you won’t hear Justin Bieber playing at my house.”

Urdaneta believes that everyone should acknowledge the privileges that they have. Coming from a place with extreme poverty and a lack of basic necessities, Urdaneta dramatically appreciates the opportunity she’s received to escape poverty and uses her voice to speak up about her home country’s issues.

“I definitely go through this story with my friends a lot. When they say certain [insensitive] things or act a certain way, they seem ungrateful,” Urdaneta said. “I just think that people should be a lot more grateful for what they take granted for granted because it could be so much worse. It’s about being grateful for what you do have.”

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customer’s car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. “[If] they’re trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,” Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. “The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring — Parkway’s Four C’s — in the process,” Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone family’s band “Monte and the Machine” has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. “My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],” Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Amid teaching a lesson to her AP Calculus BC class, Kristin Judd jokes alongside her students in their funny remarks. Judd has always enjoyed keeping the mood light in her classroom, along with on the volleyball court. “[I enjoy] that side talk where you see [or] overhear a conversation and chime in, or somebody says something funny,” Judd said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/image-1200x730.jpg)

![Eyeing the ball, junior Ella McNeal poses for her commitment pictures at Clemson University. McNeal’s commitment comes after months of contact with top Division 1 soccer programs. “ It has taken a lot to get to where I am, but I know that [what] I've already been through is just the beginning, and I can't wait for what is to come,” McNeal said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_4926-1200x900.jpeg)

![Senior Adam Zerega stands with senior Dexter Brooks by farm equipment. Zerega often worked with friends and family on his farm. “I've been able to go to my family's farm since I was born. I [spend] at least three weekends a month [on the farm], so I'm there all the time,” Zerega said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IMG_4872-1200x900.jpg)

![After a thrilling point, senior Katie Byergo and junior Elle Lanferseick high-five each other on Oct. 8. With teamwork and camaraderie, Byergo worked together in the game against Lafayette High School. “[Byergo’s] is really positive with a good spirit,” Lanferseick said. “I set her [the ball] and she hits it [or] gets the kill.”](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_9349-1-e1761159125735-1200x791.jpg)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. “My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,” Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. “[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadn’t really had a good opportunity to do until now. It’s [really] fun being out [on the field], and I’m glad I decided to join the team. It’s just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,” Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

![Red, white and blue, the American flag holds the values of our democracy. The fight that we once endured has returned, as student journalists and senior correspondents across the country are losing their voices due to government control. “[Are] the White House and [the] government limiting free speech [and] freedom of the press? Yes [they are],” chief communications officer of the Parkway School District and former journalist Elisa Tomich said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Untitled-design-14.jpg)

![Freezing in their position, the Addams Family cast hits the “rigor mortis” pose after cast member and senior Jack Mullen, in character as Gomez Addams, calls out the stiff death move. For the past four months, the combined company of cast members, orchestra pit, crew and directors all worked to create the familial chemistry of the show. “I’m excited for [the audience] to see the numbers, the music, the scenes, but I also just love all the technical aspects of it. The whole spectacle, the costumes, makeup and the people that put in the work backstage in order to make the show successful on stage. I’m excited for people to see and appreciate that,” Mullen said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/DSC0116-1200x800.jpg)