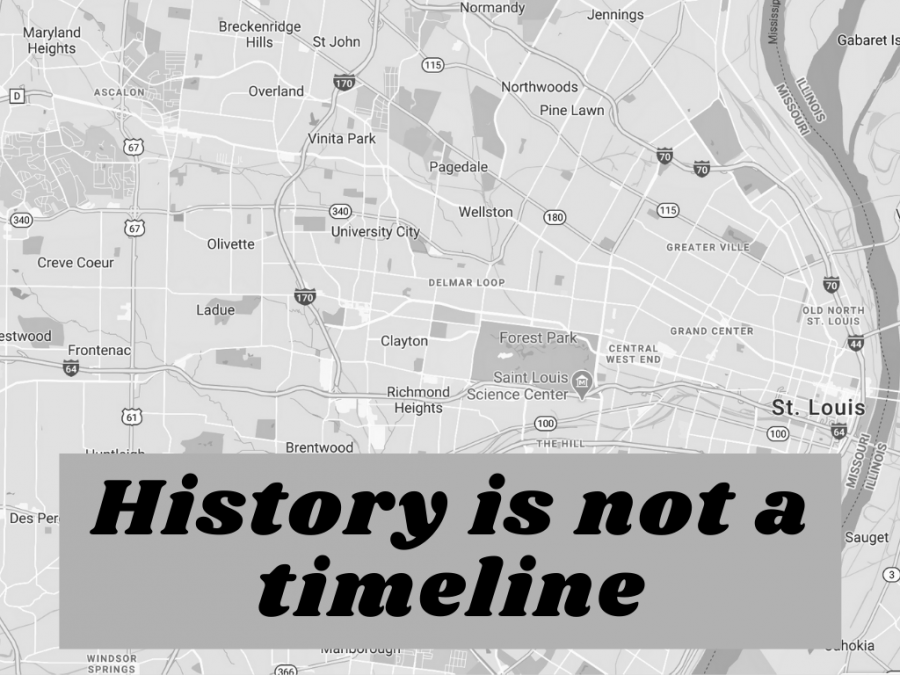

From chapter one to chapter two, year after year, we highlight vocab terms of isolated events: revolutions, laws, court cases. This is generally how we are taught historyŌĆöa series of systems and policies that begin and end at certain times. This approach is often designed to shield us from historical nuance and uncomfortable truths.┬Ā

The stories of the past, however, are cyclical and interconnected, not linear or individual. This is perhaps most apparent during Black History Month. As we learn about past Black leaders and movements, we must also reflect on how oppressive forces have evolved over time. History should be analyzed in a structural way, tracing the systems of the past to their effects on the present.┬Ā┬Ā

These issues of oversimplification and disconnectedness are present in the way we review even local history in the St. Louis region. St. Louis has long been an epicenter of segregationŌĆöand consequently revolution. The history of segregation permeates all aspects of the region. From housing to wealth distribution to policing, the effects of racist policies continue to exacerbate inequality today. But it is in the school system where the consequences are most visible.

Early history of the education system┬Ā

The story of the education system in St. Louis begins in 1838 when the first public school was established. In the next three decades, more than 20 schools were built for white students. Meanwhile, in 1847, Missouri prohibited the education of free and enslaved Black people by passing an anti-literacy law. The law criminalized anyone who attempted to teach Black people in the state, out of fear that their education would be a threat to the system of slavery. It was only after the Civil War in 1865 that a newly formed Board of Education for Colored Schools opened five schools for Black students in St. Louis. Not only were there fewer schools for Black students, but the quality of the facilities and the education were by no means comparable. By 1875, there were twelve additional segregated public schools, amongst them the first African American high school west of the Mississippi River, Sumner High School. This early history, characterized by structural anti-Blackness, set the stage for what came next in the education system.

20th century and segregation┬Ā

At the start of the 20th century, St. Louis City had more than 35,000 African-American residents. This was evidently a problem for the white citizens of the city in continuation strongly disapproved of the substantial increase in Black residents. Despite the policy reforms of the previous century, the citizensŌĆÖ sentiments persisted and were put into action. They passed a ballot initiative in 1916, a law that required white and Black residents to live in segregated neighborhoods. This was legally challenged and overturned a year later, but residents found loopholes like redlining and real estate covenants, which effectively wrote segregation into housing contracts and divided the city into what is commonly known today as the Delmar Divide.┬Ā

This housing segregation, further intensified by white flight, solidified schooling segregation. The St. Louis Public Schools district (SLPS) created a dual school system separating students by race. The United States Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson required the SLPS to provide separate but equal facilities. Not only did this decision codify Jim Crow laws, but the education system that the school board designed could hardly even be considered equal.

For instance, reports documented overcrowding, poor facilities and lack of opportunities that served as clear evidence for inequality within the 24 segregated school districts in the region. In the 1946-47 school year, the St. Louis Board of Education spent $219.77 per white high schooler and $177.09 per Black high schooler. This funding pattern, which continues to this day, shows the consistent prioritization of white students. In this time period, Black families and other groups brought numerous legal challenges against segregation, but race-separated institutions persisted. Entering 1954, the year of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court decision, St. Louis had the second-largest segregated school district in the country.

Desegregation following Brown v. Board of Education

After the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which concluded that separate schools are incontrovertibly unequal, desegregation was not immediately achieved. Initially, school board officials vowed to voluntarily integrate schools without outside programs or local laws, but they simply redrew district lines and perpetuated segregation. Nearly 30 years after the courtŌĆÖs decision, 90% of Black students in the city still attended predominantly Black schools; the school boardŌĆÖs voluntary integration was created and implemented in bad faith.┬Ā

After a lawsuit brought by a group of Black parents against the school board, federal judge William Hungate called for a plan in 1981 to move Black St. Louis children to white suburban schools via bussing programs. As with past integration efforts, white suburban residents responded with widespread resistance and anger. The judge responded by threatening to completely dissolve all 24 school district boundaries. White residents, who were still against full integration, promptly dropped outspoken dissent as a result. In 1983, the countryŌĆÖs largest interdistrict school desegregation program began.┬Ā

The Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation (VICC) reached its peak enrollment of 14,626 students in 1999. For students who participated in the program, scores and graduation rates increased while some barriers to opportunity decreased. But even with its success, another 15,000 students were left in segregated and often poorly funded schools. Additionally, the VICC program was forced into a continual phase-out, and will stop accepting new enrollment after the 2023-24 school year.

Today

Nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education the educational system in St. Louis and other cities across the country remain largely segregated and unequally funded. Parkway and other wealthy, predominantly white districts are clear examples of this.┬Ā

The tri-county dissimilarity index score for St. Louis City, St.Louis County and St. Charles Country was about 0.80 in 1968, meaning that at the time, 80% of Black or white students would have to move across districts to be distributed proportionally. (A dissimilarity index of zero indicates total integration, while a score of 100 indicates conditions of total segregation.) As recently as 2019, Forward Through Ferguson reports that this number has only decreased to 0.71.

Funding wise, the pattern is the same: white-dominated school districts are able to spend more on each student than their majority Black counterparts. The highest-spending majority-white district had a margin of almost 40% ($8,412) more spent per student in comparison to the highest spending majority Black district. When compared to the lowest-spending districts, majority-white districts spent 2.4 times (about $18,000) more per student.┬Ā

As students being educated in one of the wealthiest districts in the region, we must understand the context of how this came to be. If we view this history in an exclusively linear framework, we might come to the conclusion that the unequal distribution of resources and the other injustices present in our public schools today are simply mishaps. On the other hand, if we examine the complexities of history in a thematic way, we can better understand how past events have evolved into todayŌĆÖs reality.

![Dressed up as the varsity girlsŌĆÖ tennis coach Katelyn Arenos, senior Kate Johnson and junior Mireya David hand out candy at West HighŌĆÖs annual trunk or treat event. This year, the trunk or treat was moved inside as a result of adverse weather. ŌĆ£As a senior, I care less about Halloween now. Teachers will bring their kids and families [to WestŌĆÖs Trunk or Treat], but there were fewer [this year] because they just thought it was canceled [due to the] rain. [With] Halloween, I think you care less the older you get,ŌĆØ Johnson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC00892-1-1200x800.jpg)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. ŌĆ£My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,ŌĆØ Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Red, white and blue, the American flag holds the values of our democracy. The fight that we once endured has returned, as student journalists and senior correspondents across the country are losing their voices due to government control. ŌĆ£[Are] the White House and [the] government limiting free speech [and] freedom of the press? Yes [they are],ŌĆØ chief communications officer of the Parkway School District and former journalist Elisa Tomich said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Untitled-design-14.jpg)

![A board in the Parkway West counseling department displays pennants of selective universities. With a wide range of students interested in attending, itŌĆÖs important that these schools have clear priorities when deciding who to admit. ŌĆ£[Washington University] had the major that I wanted, psychology, philosophy, neuroscience. That's a holistic study of the brain, and [WashU is] the only college in the world that offers that. That's the main reason I wanted to go; I got into that program,ŌĆØ senior Dima Layth said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Flag-1.png)

![Within the U.S., the busiest shopping period of the year is Cyber Week, the time from Thanksgiving through Black Friday and Cyber Monday. This year, shoppers spent $13.3 billion on Cyber Monday, which is a 7.3% year-over-year increase from 2023. ŌĆ£When I was younger, I would always be out with my mom getting Christmas gifts or just shopping in general. Now, as she has gotten older, I've noticed [that almost] every day, I'll open the front door and there's three packages that my mom has ordered. Part of that is she just doesn't always have the time to go to a store for 30 minutes to an hour, but the other part is when she gets bored, she has easy access to [shopping],ŌĆØ junior Grace Garetson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/DSC_0249.JPG-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Sally Peters stands in the history hallway, contemplating her choices in the 2024 United States and Missouri elections on Nov. 5. As a member of Diplomacy Club, Peters has discussed key candidates and issues in contemporary American politics. ŌĆ£[As students], we're starting to become adults. We're realizing how much the policies that are enforced and the laws that make it through the House and Senate are starting to affect us. [Opportunities such as] AP [U.S.Government] and Diplomacy Club [make elections feel] a lot more real,ŌĆØ Diplomacy Club vice president and senior Nidhisha Pejathaya said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Flag-1-1.png)

![Sophomore Shree Sikkal Kumar serves the ball across the court in a match against Lindbergh. Sikkal Kumar has been a varsity member of the varsity girlsŌĆÖ tennis team for two years, helping her earn the number two rank in Class 2 District 2.ŌĆ£When matches are close, itŌĆÖs easy to get nervous, but I [ground] myself by[staying] confident and ready to play,ŌĆØ Sikkal Kumar said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC2801-1200x798.jpg)

![Focused on providing exceptional service, sophomore Darsh Mahapatra carefully cleans the door of a customerŌĆÖs car. Mahapatra has always believed his customers deserve nothing less than the best. ŌĆ£[If] theyŌĆÖre trusting us with their car and our service, then I am convinced that they deserve our 100 percent effort and beyond,ŌĆØ Mahapatra said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0018-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Aleix Pi de Cabanyes Navarro (left) finishes up a soccer game while junior Ava Muench (right) warms up for cross country practice. The two came to Parkway West High School as exchange students for the 2025-2026 school year. ŌĆ£The goal for the [exchange] program is to provide opportunities for both Parkway students and our international exchange students to learn about other cultures, build connections and become confident, capable, curious and caring ŌĆö ParkwayŌĆÖs Four CŌĆÖs ŌĆö in the process,ŌĆØ Exchange Program Lead Lauren Farrelly said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Feature-Photo-1200x800.png)

![Gazing across the stage, sophomore Alexis Monteleone performs in the school theater. The Monteleone familyŌĆÖs band ŌĆ£Monte and the MachineŌĆØ has been releasing music since 2012, but Alexis started her own solo career in 2024 with the release of her first single, Crying Skies. ŌĆ£My whole family is very musical, [and I especially] love writing [songs with them],ŌĆØ Monteleone said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7463-1200x798.jpg)

![Leaping through the air, senior Tyler Watts celebrates his first goal of the season, which put the Longhorns up 1-0 against the Lafayette Lancers. Watts decided to play soccer for West for his last year of high school and secured a spot on the varsity roster. ŌĆ£[Playing soccer for West] is something I had always dreamed of, but hadnŌĆÖt really had a good opportunity to do until now. ItŌĆÖs [really] fun being out [on the field], and IŌĆÖm glad I decided to join the team. ItŌĆÖs just all about having fun with the boys and enjoying what time we have left together,ŌĆØ Watts said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_1951-1200x855.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald TrumpŌĆÖs tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. ŌĆ£[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,ŌĆØ social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,ŌĆØ Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)