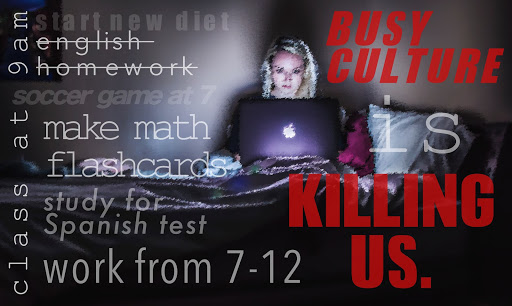

I had a conversation recently that baffled me. We were discussing our schedules, and a peer shared with me that, alongside their AP-filled class schedule, they were holding down a part-time job, participated in nearly 20 extracurricular activities and, among those activities, held a leadership position in at least five of them.

ŌĆ£When do you sleep?ŌĆØ I asked.

ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt,ŌĆØ they replied, smiling.

What surprised me the most from this exchange was not the astounding number of responsibilities this student was holding downŌĆö although it was something to marvel atŌĆöit was my reaction. I felt jealous.

This made me question my heart. Why is this something I envy? Am I not working hard enough? Am I getting too much sleep? These thoughts sprinted through my head, tearing apart all of the pride I built up over the past four years. I spent my high school career busy doing things that I love. In the meantime, did I miss out on impressing a college admissions officer with my multitude of extracurriculars?

I got swept up in the tornado of the ŌĆ£busy brag.ŌĆØ

┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā Why brag about busyness?

In the past, the rich flaunted their ease of life, while the average English worker labored for 64 hours a week. In the 19th century, you could tell how poor somebody was by how long they worked.

Now, studies reveal a stark change in that data. The American Time Use Survey conducted by the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that in 2019, those with an educational attainment of less than a high school diploma spent close to six hours a day on leisure and sports activities. In contrast, those with advanced degrees spent about an hour and a half less doing those same activities.

If you stopped looking there, you could come to the inaccurate conclusion that those with lower educational attainment are simply lazy. If we completely disregard the many reasons why those with less education were unable to pursue a higher education, such as lack of family support, fewer opportunities and inability to pay for costly secondary education, we still have many explanations for this contrast in leisure time, such as the substitution effect.

The substitution effect makes leisure time for those with higher wages, which are most commonly those with a higher educational attainment, more expensive. Adjusting for inflation, salaries since the 1980s have risen sharply for those at the top, while salaries below the median have fallen. WeŌĆÖve created a labor system with built in incentives for taking less time off. But our labor system not only celebrates this overworked workforce, it makes it necessary. For some, locking in financial stability for themselves and their families is impossible without shortchanging their personal lives and mental and physical wellness.

While most of us havenŌĆÖt entered the workforce yet, our daily lives are still infiltrated by the unhealthy values that busyness in the work culture uphold. If those who have a higher educational attainment and higher wages use less of their time on non-work activities, those of us who plan to have a similar career in the future will follow suit, causing the ŌĆ£image of successŌĆØ to be busyness.

┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬ĀA new addiction

Busyness is an addiction. But unlike alcoholism or drug addictions, it is accepted and even praised. Busyness can imply that we are wanted and needed, making us feel more valuable, and sharing this with others lets them know just how hot of a commodity we are.

How does this put our relationships at risk, you may ask? How many times have you invited someone to lunch and heard,┬Ā ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm sorry, IŌĆÖm slammed, maybe next week,ŌĆØ yet they never reach out again? Or when youŌĆÖre telling someone a story, and when you look up, theyŌĆÖre answering emails, nodding every five seconds to feign their interest. These experiences are painful and devaluing.

There are, of course, times when our lives are truly non-stop, and we need to enter tunnel vision to reach our deadlines and finish our to-do lists, forgoing sleep, leisure time and relationships for work, work and more work. But if this perpetual filled-to-the-brim schedule is your daily life, and your relationships and mental and physical health are falling apart beyond repair, then it is vital to take a step back and prioritize differently.

┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā ┬Ā Get your priorities straight.

Returning to my original anecdote, when this conversation occurred, I was deep in the throes of my need to be busy. I felt validated by what I could create and how much I was involved in because it made me feel needed, and I feared that not doing ŌĆśenoughŌĆÖ would make colleges, friends and teachers lose all interest in me.

After speaking with this busy peer, I was jealous. I was jealous, and I was worried. Worried that the types of people being accepted into great colleges were people like this peer, not people like me. That schools and the workforce valued exhausted, exploited, overworked people that externally grinned their way through the pain that is busyness, while internally falling apart.

And that is true. Most of the systems that surround us are impersonal and numbers based, without true regard for their workers who grind day-in and day-out for the companyŌĆÖs higher ups.

But it doesnŌĆÖt have to stay this way.

These problems are structural; If we never begin to understand the inherent problem with busy culture and our hand in it, we will never make the changes necessary to lessen busy cultures’ effects on us.

We must realize that we are worth more than our career status, more than what we can create, more than our labor, more than our AP classes and our grades and our future salaries.

Understanding that our need to be busy is just a response to the structures that surround us and their exploitation of workers frees us to slow down, take a moment and realize where our value actually comes from.

![Dressed up as the varsity girlsŌĆÖ tennis coach Katelyn Arenos, senior Kate Johnson and junior Mireya David hand out candy at West HighŌĆÖs annual trunk or treat event. This year, the trunk or treat was moved inside as a result of adverse weather. ŌĆ£As a senior, I care less about Halloween now. Teachers will bring their kids and families [to WestŌĆÖs Trunk or Treat], but there were fewer [this year] because they just thought it was canceled [due to the] rain. [With] Halloween, I think you care less the older you get,ŌĆØ Johnson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC00892-1-1200x800.jpg)

![Leaning on the podium, superintendent Melissa Schneider speaks to Parkway journalism students during a press conference. Schneider joined Parkway in July after working in the Thompson School District in Colorado. ŌĆ£My plan [to bond with students] is to get things on my calendar as much as possible. For example, being in [classes] is very special to me. I am trying to be opportunistic [meeting] kids [and] being in [the school] buildings. I have all the sports schedules and the fine arts schedules on my calendar, so that when I'm available, I can get to them,ŌĆØ Schneider said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_5425-1200x943.jpeg)

![Red, white and blue, the American flag holds the values of our democracy. The fight that we once endured has returned, as student journalists and senior correspondents across the country are losing their voices due to government control. ŌĆ£[Are] the White House and [the] government limiting free speech [and] freedom of the press? Yes [they are],ŌĆØ chief communications officer of the Parkway School District and former journalist Elisa Tomich said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Untitled-design-14.jpg)

![A board in the Parkway West counseling department displays pennants of selective universities. With a wide range of students interested in attending, itŌĆÖs important that these schools have clear priorities when deciding who to admit. ŌĆ£[Washington University] had the major that I wanted, psychology, philosophy, neuroscience. That's a holistic study of the brain, and [WashU is] the only college in the world that offers that. That's the main reason I wanted to go; I got into that program,ŌĆØ senior Dima Layth said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Flag-1.png)

![Within the U.S., the busiest shopping period of the year is Cyber Week, the time from Thanksgiving through Black Friday and Cyber Monday. This year, shoppers spent $13.3 billion on Cyber Monday, which is a 7.3% year-over-year increase from 2023. ŌĆ£When I was younger, I would always be out with my mom getting Christmas gifts or just shopping in general. Now, as she has gotten older, I've noticed [that almost] every day, I'll open the front door and there's three packages that my mom has ordered. Part of that is she just doesn't always have the time to go to a store for 30 minutes to an hour, but the other part is when she gets bored, she has easy access to [shopping],ŌĆØ junior Grace Garetson said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/DSC_0249.JPG-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Sally Peters stands in the history hallway, contemplating her choices in the 2024 United States and Missouri elections on Nov. 5. As a member of Diplomacy Club, Peters has discussed key candidates and issues in contemporary American politics. ŌĆ£[As students], we're starting to become adults. We're realizing how much the policies that are enforced and the laws that make it through the House and Senate are starting to affect us. [Opportunities such as] AP [U.S.Government] and Diplomacy Club [make elections feel] a lot more real,ŌĆØ Diplomacy Club vice president and senior Nidhisha Pejathaya said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Flag-1-1.png)