Student and community organizers are calling on schools across the country to cut their ties with police departments. While campaigns to remove armed officers from school campuses have been ongoing for years, the recent national uprising against police violence sparked by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd reignited this fight.

The School Resource Officer Program dates back to the mid-1950s, with schools introducing officers to foster positive relationships between students and law enforcement. However, the late 20th century’s rise of zero-tolerance policies in schools resulting from the over criminalization of the “tough on crime” era, coupled with the aftermath of the Columbine High School mass shooting, led to a shift in the initiative’s original goals. In that period, there was an increase in sworn police officers stationed in schools. This all came at a colossal cost.

Over-policing, punishment and the school-to-prison pipeline:

Advocates of police-free schools say that through School Resource Officers (SROs) may try to create a safe environment for students, research and student experiences shows that relying on armed personnel creates a toxic environment for students of color, particularly Black students and feeds the school-to-prison pipeline. This is a trend in which students of color are disproportionately pushed from public schools into the criminal legal and juvenile systems as a result of over criminalization and punishment for minor disciplinary incidents at school.

“In the morning before classes start, there’s the police officer and all the teachers [standing] there [next to a group of Black students]. After the bell rings, they will just stand there waiting for a student to come. If it’s a Black student on their way to class or doing something else, they only stop them. They only go for them,” senior Bri Davis said. “Same thing at lunch; a lot of the Black students don’t really sit in the cafeteria. They sit outside or they go to a teacher’s classroom, things that everyone else has access to do. Yet there’s a teacher everywhere they go. It’s constant watching and it’s unnecessary. I feel like the police officer can do a lot more than just stand there waiting for something to happen and looking at us [Black students] like we’re the bad people.”

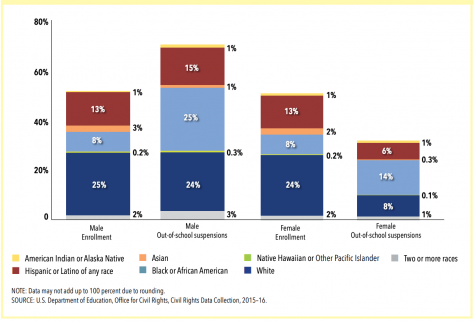

Data by the U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights Data Collection, 2015-2016.

Senior Kayla Stephenson, who usually sits in the junior principal’s office in the mornings before class, shares similar observations.

“I feel like this school is always watching the Black students. I see maybe one teacher who stands out there with all the sophomores [where] a lot of things go on: a lot of screaming, a lot of chaos. But I feel that the teachers are downstairs where the Black people are,” Stephenson said. “There was one situation where me and a group of friends were walking the hallways downstairs by the cafeteria because we were staying after school. A teacher who was White had come up to us and told us that we can’t be roaming the halls or we get in trouble. There was a group of White people walking around the hallways, but we got confronted about it and they didn’t. So I feel like not every person is after Black students, but in some situations, White people have more power than a Black person.”

As demonstrated by nationwide data from the U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection, these students are not alone in their experiences. During the 2015–16 school year, Black students made up 31% of students who were referred to law enforcement or arrested when they were only 15% of the total student enrollment—a 16% point disparity.

“Sometimes I do think that [the over watching] is intentional. We [Black students] are just being a student like everyone else. But they’re just putting people like administrators and teachers here and there just in case [something] happens, and most of the time, nothing’s happening,” Davis said. “We’re just talking and hanging with our friends. It’s frustrating because it’s not just in the morning, it’s all throughout the day until the end of the day.”

While School Resource Officer Zeus Hernandez understands that some students may not be comfortable with police officers due to past negative experiences, he says his role is to protect students and staff and to create a good relationship between the student body and the police department.

“I don’t want to bring the racial aspect into it simply because I’ve been asked to be all over the place whenever there is the need. So literally, if you see me in one place at one time or primarily in one place, often it’s because I’ve been directed to be there,” Hernandez said. “I certainly understand how it is from an outside view. If you did not know that, it looks like I’m in one place at one time viewing one group of people all the time. However, it’s important to know that I’m there because I’m told to be there.”

On each floor, there are administrators placed based on grade level, with the SRO outside the cafeteria.

“I do ask Officer Hernandez to go to the first floor [because] we feel like there’s a greater concentration of kids in the cafeteria. I will say that it wouldn’t matter who is standing in that area. As long as we still have a cafeteria there, and we have a lot of action, we’re going to have folks there,” Principal Jeremy Mitchell said. “Our goal is not for people to feel like they’re being watched. It’s for us to be present and be able to provide an adult person to talk to if need be.”

But Stephenson and Davis explain that feeling over watched is not the only thing they experience. They also say that Black students at West are more likely to be suspended and for longer. While they don’t know everyone in the school, they know of many cases where this has happened. In the Parkway School District, Black students are 4.5 times more likely to be suspended.

Data by the U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights Data Collection, 2015-2016

“I’ve seen some situations at school where a Black person and a White person get into a situation and the White person does something to the Black person, and in turn, the Black person got suspended instead of the White person,” Stephenson said. “Or both got suspended but the Black person got suspended longer.”

In Missouri, American Civil Liberties Union data from the 2017-2018 school year showed that Black students were five times more likely to receive an out of school suspension than their White peers. Overall suspension rates have decreased in the district, but Mitchell says the numbers are still disproportionate and that there are ongoing conversations about this issue.

“Even if I’m not friends with all Black students at the school, when they’re talking to me, they’ll talk about being suspended and they’ll tell me what happened. I’ll [say] ‘well, that doesn’t really sound fair, you didn’t do anything wrong’,” Davis said. “It’s a consistent thing that I’ve seen in high school all four years now [and] we’re not the only ones that are doing something wrong.”

SRO Training:

SROs are sworn police officers. They receive regular police training in addition to a school-specific training.

“There is separate training that is certainly focused on the school atmosphere because let’s be honest, the school setting is not like the street settings,” Hernandez said. “These are kids who have a bunch of hormones going through them and they may not be thinking thoroughly. They send us to a specific training just for us to be aware of how to transition into schools, how to maintain a good level of understanding of how schools work and how we can still apply the law accordingly, because there is a big difference between how the school handles things and how we as police officers handle them. Our goal is to bridge that gap in the training.”

Hernandez also receives cultural competency training to understand different beliefs as well as mental health training to better handle those cases. He says he is always willing to go through more training to gain further experience.

“There are a lot of times where in a school, especially where you have diversity, it’s important for us to be aware of those different beliefs, those different faiths, those different views and how to handle them,” Hernandez said.

Stephenson and Davis say that police officers in the Black community can sometimes be aggressive and that officers in school can operate in similar ways.

“There is a huge connection when it comes to a police officer in school and a police officer in an everyday community. You just see the same thing: a police officer who’s just looking for that one person, and thinking that they’re doing something wrong,” Davis said. “That’s where accidents come into play. The connection, I want to break it, because it shouldn’t be that way at all. We are kids, we are not adults.”

Open letter calling on Parkway to audit SROs’ impact:

2013 alumna Annie Schuver, along with alumni Jake Lyonfields, Jack Seigel and James Wang, wrote an open letter that calls on district leaders to create a “Safety for All Students” task force. The task force would conduct an audit on the impact of SROs in the district through a racial justice lens and recommend appropriate action.

“The group of alumni that co-authored the letter with me were talking about the protests and the events that unfolded and also trying to question how all of this related to our own communities,” Schuver said. “That’s what led us to deciding to do an audit. Even though there’s a lot of existing research, some of it cited in our letter, about the impact of school resource officers, especially on non-White students, that’s out there in the world, we wanted to know what that looks like specifically in Parkway.”

Schuver hopes the letter will bring attention to this issue to the entire community, while centering the most impacted students.

“There are more extreme cases that have shown School Resource Officers getting involved and it escalates into an act of violence against the student and of course that’s not acceptable. Those instances I hope and I believe are more rare,” Schuver said. “On a more subtle note is what the police represent and what they represent in different communities, so it might feel like a more hostile learning environment for students whose communities have been impacted negatively by law enforcement. Every student should have a place where they feel safe to learn and where they feel like they can focus on their education first, and they shouldn’t be worrying about anything beyond that.”

The letter notes that Parkway spends $721,754 yearly on SROs without evaluating its impact.

“We should be evaluating the impact of the things we’re spending our money on. Our budget and the way we use our taxpayer dollars are reflections of our values,” Schuver said. “And so we want to make sure that we evaluate whether or not [SROs] are increasing safety.”

Solutions and alternatives:

Communities across the country are pushing towards non-punitive methods to create safety for students. Advocates are calling for alternatives to policing that include investing in social workers, restorative justice and trauma-informed programs and de-escalation practitioners.

“There are a lot of students who come from a background where they have less money or they have a lot of problems at home. So when they come to school, they don’t know how to handle it. They don’t know how to keep it at bay,” Davis said. “Sometimes I feel like people like that are targeted a lot, because [administration and SROs] think as if [the students] can’t do things correctly, or they’re going to act out and I feel like that should be the time where the police officer at our school tries to understand, tries to talk to them. I do not think that we need police officers because sometimes it makes students feel uncomfortable.”

While the presence of SROs has increased in public schools, health resources are still lacking. For example, 14 million students are in schools with police but no counselor, nurse, psychologist or social workers.

“I think that if we could find a way to work collectively, it would be fantastic. But I don’t think there will ever be a situation where there will never be a need for the safety and security that law enforcement can provide, no matter how much or how educated someone may be,” Hernandez said. “It’s important to know that just like we have limitations with that kind of training in the roles we play in, those individuals, whether they be therapists, or counselors or mental health specialists, also have limitations.”

In recent years, Parkway has implemented some restorative justice practices and made a greater effort to address underlying issues of challenging student behavior through referrals to counselors and social workers.

“In the school, there is always a reason why people do what they do, something that sparks it,” Stephenson said. “It should be more of sitting down, talking it out and figuring out what actually happened, seeing why the person did what they did. It’s always a good idea to have alternatives, but sometimes it doesn’t work.”

The open letter urges that if the audit shows that money spent on SROs is not positively impacting student well-being and school safety, then that funding should be reallocated to initiatives such as mental health resources, resources for students with disabilities and cultural competency programs.

“I think there are a lot of answers to [alternatives] being entertained. I’m willing to defer to activists of color, especially Black activists who are leading the conversation on this. Some things that I’ve heard about have been about just investing more in students themselves,” Schuver said. “I’m hoping that through this audit, we understand better what our students need to feel safe.”

Mitchell assures that he understands the calls to reevaluate the SRO program and is willing to hear students’ opinions and experiences to understand the situation better.

“I think West needs to do a lot better. They really need to work on equality because although West promotes a lot of African American things, it’s deeper than just that,” Davis said. “It’s literally the entire day of school, not just when we’re in groups together, and they can do a lot better.”

![Smiling in a sea of Longhorns, Fox 2 reporter Ty Hawkins joins junior Darren Young during the morning Oct. 3 pep rally. The last time West was featured in this segment was 2011. “[I hope people see this and think] if you come to [Parkway] West, you will have the time of your life because there are so many fun activities to do that make it feel like you belong here. I was surprised so many people attended, but it was a lot of fun,” Young said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Edited2-1200x798.jpg)

![West High seniors and families listen as a representative of The Scholarship Foundation of St. Louis, Teresa Steinkamp, leads a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) workshop. This session, held in the library, provided guidance on financial aid, scholarships and student loan options. “This event is very beneficial for any seniors who are applying to or considering applying to colleges after high school [because] the cost of college is on the rise for seniors and parents,” college and career counselor Chris Lorenz said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_4478-1200x778.jpg)

![Senior Kamori Berry walks across the field during halftime at the Homecoming football game on Sept. 12. During the pep assembly earlier that day, she was pronounced Homecoming Queen. “I thought it was nice that the crowd [started] cheering right away. I know [my friends] were really excited for me, and my family was happy because typically non-white people don't win,” Berry said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7046-Enhanced-NR-1200x798.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

![The Glory of Missouri award recipients stand with their certificates after finding out which virtue they were chosen to represent. When discovering their virtues, some recipients were met with contented confirmation, while others, complete surprise. “I was not at all surprised to get Truth. I discussed that with some of the other people who were getting the awards as well, and that came up as something I might get. Being in journalism, [Fellowship of Christian Athletes and] Speech and Debate, there's a culture of really caring about truth as a principle that I've tried to contribute to as well. I was very glad; [Truth] was a great one to get,” senior Will Gonsior said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Group-Glory-of-Missouri.jpg)