Second lunch just ended. The cafeteria employees start to evaluate what can be served tomorrow and what will be composted. They walk over to the salad bar and compost all of the vegetables because they are considered contaminated and unfit to eat for a second day.

“It’s only two inches of product in [the salad bar pans], which is two pounds. But then you have 15 pans right there, [and] no one takes any of it or they just take a little nibble of cauliflower,” food service regional manager Kenny Witte said. “Then it just all goes into the compost. It’s pretty unfortunate.”

Every day, food waste from lunches is composted or thrown into the trash. Many students aren’t educated on how to dispose of food properly, as witnessed by custodian Sean Smith.

“I put on two pairs of gloves for safety sanitization, and I dig through and get what should be in the yellow [compost bins]. Do I prefer to do that? Not really, but I would do my part to help get it right,” Smith said.

Although informational signs have been posted directing students how to dispose correctly, custodians and district leaders still see room for growth.

“I’m working with the custodians at West High to help get them on board as far as helping us sort through during the lunch shift,” Parkway sustainability coordinator Hannah Carter said. “On top of that, the students need to be able to know how to do it.”

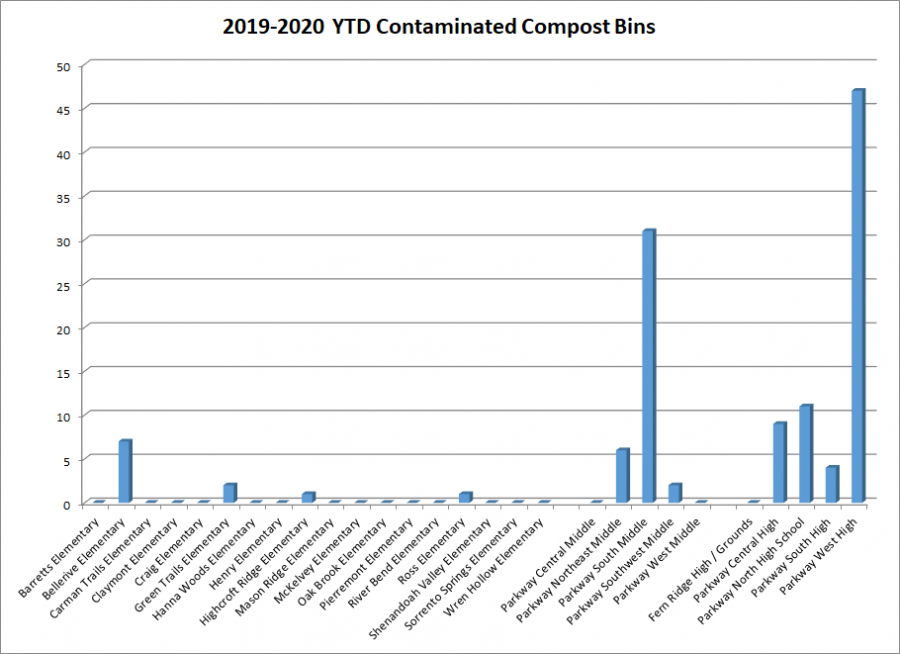

Parkway West High School has the most contaminated compost bins out of the entire district.

“For unknown reasons, Parkway West High has had a challenge over times trying to reduce the amount of contamination into the compost bin,” director of sustainability and purchasing Erik Lueders said. “[Lessening our environmental impact] is important not just for Parkway but for everyone. Across this planet, we live in a very consumerist, and unfortunately wasteful, society, that’s just kind of where we’re at.”

An infographic displaying what students can do to promote environmentally friendly practices.

Every time that trash is found in a compost bin, Parkway is fined $3 per contaminated bin by the composting company. For example, in December, West High had 33 contaminated bins, so the district paid $100 in fees. However, Parkway is more concerned about the environmental impact than the costs of composting.

“Every amount of food wasted is a lot of money wasted, but also a lot of waste generated,” Carter said. “So we addressed food waste from an environmental standpoint, more than a money standpoint, because composting isn’t cheap. We just know it’s the right thing to do.”

In addition to the most contaminated compost bins, West produces between 40,000 and 50,000 pounds of waste per month. The 2025 goal for Parkway is to reach a 70% diversion rate from the landfill; Parkway is currently at 55%.

“I think that in order to ensure that the planet can sustain environmental services and systems, the biodiversity that’s needed to do so, and mitigating climate change–which studies are showing the effects are happening much more rapidly than originally expected–we all, as a society, including Parkway, need to have a better understanding of the steps that we can take to mitigate our impact on the environment so we’re leaving future generations in a better circumstance,” Lueders said.

On average, the district produces 22,000 pounds of compost per month, which avoids the production of about 39 tons of carbon emissions.

“The climate crisis [is] real, [it’s] an urgent issue,” Carter said. “This is confusing for people to understand why landfill waste contributes to carbon emissions. When you compost, you reduce carbon emissions.”

![Smiling in a sea of Longhorns, Fox 2 reporter Ty Hawkins joins junior Darren Young during the morning Oct. 3 pep rally. The last time West was featured in this segment was 2011. “[I hope people see this and think] if you come to [Parkway] West, you will have the time of your life because there are so many fun activities to do that make it feel like you belong here. I was surprised so many people attended, but it was a lot of fun,” Young said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Edited2-1200x798.jpg)

![West High seniors and families listen as a representative of The Scholarship Foundation of St. Louis, Teresa Steinkamp, leads a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) workshop. This session, held in the library, provided guidance on financial aid, scholarships and student loan options. “This event is very beneficial for any seniors who are applying to or considering applying to colleges after high school [because] the cost of college is on the rise for seniors and parents,” college and career counselor Chris Lorenz said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC_4478-1200x778.jpg)

![Senior Kamori Berry walks across the field during halftime at the Homecoming football game on Sept. 12. During the pep assembly earlier that day, she was pronounced Homecoming Queen. “I thought it was nice that the crowd [started] cheering right away. I know [my friends] were really excited for me, and my family was happy because typically non-white people don't win,” Berry said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC7046-Enhanced-NR-1200x798.jpg)

![Pitching the ball on Apr. 14, senior Henry Wild and his team play against Belleville East. Wild was named scholar athlete of the year by St. Louis Post-Dispatch after maintaining a high cumulative GPA and staying involved with athletics for all of high school. “It’s an amazing honor. I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to represent my school [and] what [it] stands for,” Wild said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/unnamed-6-1200x714.jpg)

![The Glory of Missouri award recipients stand with their certificates after finding out which virtue they were chosen to represent. When discovering their virtues, some recipients were met with contented confirmation, while others, complete surprise. “I was not at all surprised to get Truth. I discussed that with some of the other people who were getting the awards as well, and that came up as something I might get. Being in journalism, [Fellowship of Christian Athletes and] Speech and Debate, there's a culture of really caring about truth as a principle that I've tried to contribute to as well. I was very glad; [Truth] was a great one to get,” senior Will Gonsior said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Group-Glory-of-Missouri.jpg)