In third grade, Missouri Assessment Program (MAP) testing was the best time of the year; teachers passed out Cheez-Its and Smarties periodically, there was no homework and more importantly, I didn’t have to learn history that week.

This year, when I took the practice ACT April 2, I felt no such joy. Many of my peers shared these sentiments. Though it was merely practice, I only had an appetite for stress in the morning, and I felt inadequately prepared walking into the gym. When it comes to the ACT, time is always moving too fast for me.

From a young age, we are made aware that exceptional scores in school will allow us to get into the best colleges, which will allow us to have, apparently, great lives. We are told that as school gets increasingly competitive, we must work harder and harder so that all of our dreams can come true. In every learning environment, the intensity of learning depends on the overall student population. Our school is filled with diligent, intelligent students and therefore the competition is that much more intense. When students work harder, the general standards increase, and the cycle repeats. Unfortunately, as our standards increase linearly, colleges’ standards increase exponentially.

Along with the standard that we must be phenomenal learners (to even be considered as serious applicants), elite colleges search for unique individuals: a vague and less formulaic concept. Even though a 36 is still rare, scoring a 34 or above is becoming more of an expectation rather than an accomplishment. On top of this, the expectation is to do what hasn’t been done, to stand out amongst a pool of kids who are equally trying to “stand out.” The score is important, yet, colleges claim, they care about the student outside of test scores as well. This elusive idea of what colleges actually want leads kids to over-exert themselves for four years and still come out of high school with letters of rejection.

Even for students who are the one-tenth of 1% who earn a 36, admission to the top universities is still not guaranteed. Out of the current seniors at our school, five earned perfect scores and others earned near-perfect scores. One of these seniors, with a 4.3 GPA, perfect ACT score and as a National Merit Finalist was rejected from Vanderbilt University. Another student with a similar resume got rejected from his dream school, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

ACT claims the test is meant to “motivate students to perform to their best ability;” however, more than motivation, low scores and college rejections result in devastation. We are also seeing an increase in test anxiety among students: four hours in a folding chair in the gym have the power to make or break all of your future plans—this is what school culture and whispers of college admissions tell us. At what speed one can answer multiple choice questions is certainly a marker of intelligence for some, but it is not the universal standard. Teachers tell us they value quality over quantity because demonstrating learning comes in a variety of forms– standardized tests are a harsh imposition that suppresses our individuality, and we must conform. As an end result, the score earned easily becomes a numerical value that students define themselves by. Obviously, it is not any students inclination to value exams over their own well-being; however, when it becomes a defining factor of your academic career they are left without a choice.

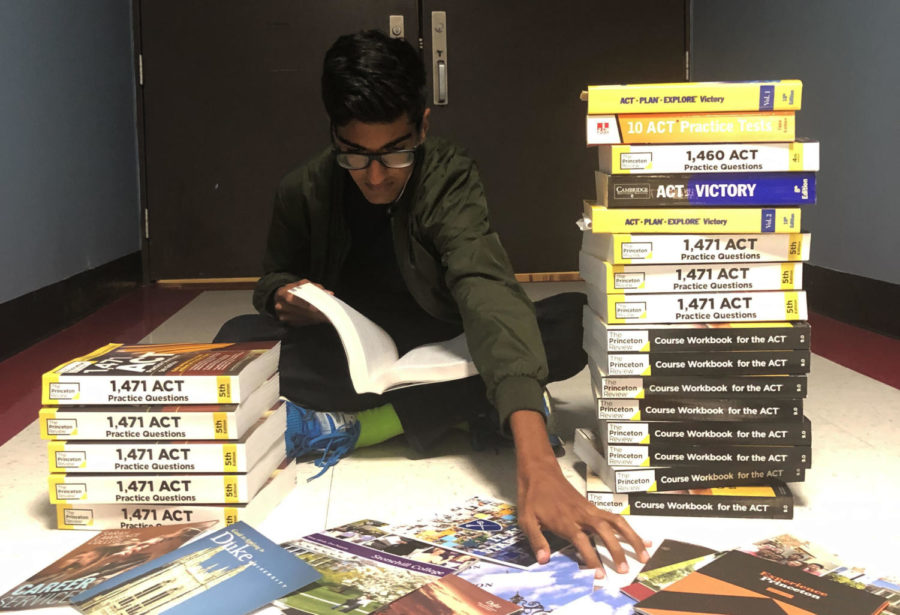

And that is why it’s unsurprising that students who are financially capable invest thousands of dollars into preparation books, tutors and to repeat the exam until they get a score they are satisfied with. After all, supposedly, a good score opens the door to prestigious college acceptances, which leads to job opportunities and having a successful life. This arises as an issue with lower-income students as they get left in the dust without the same ability to afford tutors and books.

At the end of the day, there are still thousands of kids with amazing scores competing for a very limited number of spots in the Ivy League colleges. They are being told to apply to college shotgun style: apply to a broad range of schools in the hopes that one of them will let you in. As more kids apply to more schools, overall application pools rise, and a lower percentage of applicants are admitted.

What the ACT truly assesses of students is far from perfect, and the admissions process is notably flawed. The system as a whole needs serious reformation; the impact that a two-digit number can currently have on one’s future is overwhelming. ACT needs to mitigate issues such as test anxiety and elite college culture amongst high schoolers, not exacerbate the issues. The easiest way to help high schoolers would be to get rid of standardized test scores as a requirement. We as students need to reevaluate the systems we are embedded in. Numerical values should not play such an immense role in our future ambitions.

![Sitting courtside before a junior varsity girls’ tennis match, senior Tanisi Saha rushes to finish her homework. Saha has found herself doing academic work during her athletic activities since her freshman year. “Being in sports has taught me how to stay organized and on top of my schoolwork. [With] a busy practice and game schedule, I’ve learned to manage my homework and study time better,” Saha said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC_0022-1200x800.jpg)

![Sophomore Maryem Hidic signs up for an academic lab through Infinite Campus, a grading and scheduling software. Some students enjoyed selecting their responsive schedule in a method that was used school-wide last year. “I think it's more inconvenient now, because I can't change [my classes] the day of, if I have a big test coming and I forget about it, I can't change [my class],” sophomore Alisha Singh said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0012-1200x801.jpg)

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)

![Junior Fiona Dye lifts weights in Strength and Conditioning. Now that the Trump administration has instituted policies such as AI deregulation, tariffs and university funding freezes, women may have to work twice as hard to get half as far. "[Trump] wants America to be more divided; he wants to inspire hatred in people,” feminist club member and junior Clara Lazarini said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Flag.png)

![As the Trump administration cracks down on immigration, it scapegoats many immigrants for the United States’ plights, precipitating a possible genocide. Sophomore Annabella Whiteley moved from the United Kingdom when she was eight. “It’s pretty scary because I’m on a visa. When my visa expires next year, I’m not sure what’s going to happen, especially with [immigration] policies up in the air, so it is a concern for my family,” Whiteley said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0077-7copy.jpg)

![Shifting global trade, President Donald Trump’s tariffs are raising concerns about economic stability for the U.S. and other countries alike. “[The tariffs are] going to pose a distinct challenge to the U.S. economy and a challenge to the global economy on the whole because it's going to greatly upset who trades with who and where resources and products are going to come from,” social studies teacher Melvin Trotier said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MDB_3456-1200x800.jpg)

![Some of the most deadly instances of gun violence have occurred in schools, communities and other ‘safe spaces’ for students. These uncontrolled settings give way to the need for gun regulation, including background and mental health checks. “Gun control comes about with more laws, but there are a lot of guns out there that people could obtain illegally. What is a solution that would get the illegal guns off the street? We have yet to find [one],” social studies teacher Nancy Sachtlaben said.](https://pwestpathfinder.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_5122-1200x800.jpg)